Carbon Fiber Explained: What It Is, How It Works, And Why It's So Expensive

If there's one fascinating fact about spiders that everyone knows, it's that their silken webs are deceptively strong. It can have a tensile strength of up to around 1000 megapascals, which can be stronger than steel. The most surprising thing about this is the way that it subverts typical notions of weight and strength. A spider web is a lot of powerful, lightweight strands in a very compact package, and so is carbon fiber.

Roger Bacon was one of the very first to develop carbon fibers as we understand them today. At Union Carbide's Parma Technical Center in the 1950s, he was experimenting with heating and pressurizing graphite when he found that the process created a very unique form of carbon. Incredibly delicate yet very strong, the American Chemical Society states that Bacon described them as "whiskers ... only a tenth of the diameter of a human hair, but you could bend them and kink them and they weren't brittle."

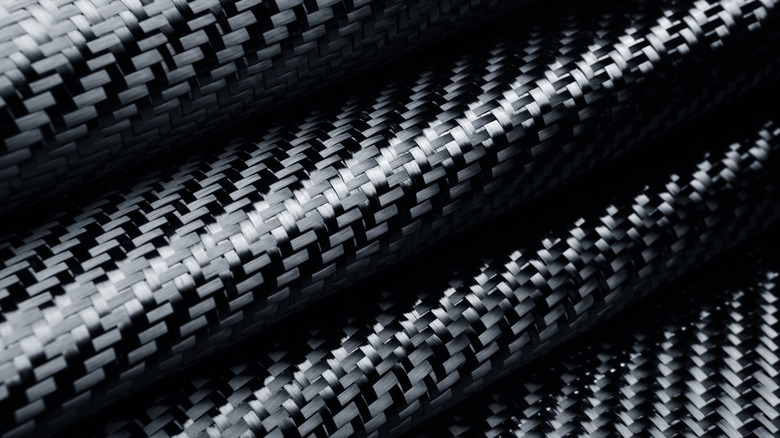

Naturally, the process of developing carbon fiber has advanced somewhat since then, but this core fact hasn't changed at all: carbon fiber is composed of numerous very thin strands, which are both incredibly light and incredibly strong. Here's a closer look at the intriguing material, how it's used, and why it's so costly to produce.

The incredible strength of carbon fiber

The process of creating carbon fiber today still involves the blend of pressure and heat that Bacon unexpectedly discovered. The precious fibers are carefully heated and carbonized into strong, thin strands that have astonishing tensile strength when woven together (a similar process to making a length of rope). Deprived of air, they don't simply burn to nothing as they would otherwise have done.

The lightweight and remarkably resilient material that results has revolutionized a range of industries. Carbon nanotube fibers have been developed that boast a tensile modulus (a way of measuring how much pressure external forces put on a given material) comparable to the likes of Kevlar. In this way, the technology has been employed in ballistic armor. From everyday objects like fishing poles and car accessories to the Boeing 787 Dreamliner, the body and fuselage of which heavily incorporate carbon fiber, there are endless uses for a hard-wearing material that doesn't weigh the finished product down.

Carbon fiber does, however, have some substantial shortcomings, not least of which is how expensive it is to create.

Why carbon fiber is so expensive

Compared to its more conventional metal alternative, manufacturing is more complex, the process tends to need to be tailored to the specific end product, and demand, as yet, hasn't reached the point at which it is as widely worked with.

Carbon fiber is typically made from polyacrylonitrile, which is formed into fibers then treated to ensure they'll maintain their closely-bonded pattern. The exposure to extreme heat that follows ensures that what remains is almost solely carbon atoms. This thread is then shaped to suit the specific carbon fiber's purpose, either woven (rather like one would on a loom) or treated further to bond with a plastic material. The potential differences in the process reflect the versatility of the material.

Additionally, special manufacturing equipment and the cost to power it drives up the ultimate price. Between January and June 2023, Procurement Resource noted that polyacrylonitrile carbon fiber, in its raw form, cost $11.11 per kilogram. This is slightly over half of the price of manufacturing it, and factoring in the rest of the work, it all adds up to a market price of approximately $28 for a kilogram over that period in China.

Though the price has been decreasing in recent years, it's not yet clear whether carbon fiber will be more widely adopted in the future.

The future of carbon fiber

The future of carbon fiber and similar materials seems even brighter. In February 2022, the University of Wisconsin-Madison announced that it had developed an incredible new material. Phys.org reports, Engineering physics assistant professor Ramathasan Thevamaran said, "Our nanofiber mats exhibit protective properties that far surpass other material systems at much lighter weight." The material, a blend of Kevlar and carbon nanotubes, hints at just where the technology may be going, but it's important to note the limitations of carbon fiber.

NASA scientists have recently been working on a similar material that blends carbon fiber's strength with metal-based constructions' ability to distribute heat across its surface. In this regard, the former is rather more delicate, and so this is a weakness that must be taken into account. In practical terms, too, the price of carbon fiber is a concern to take on board.

Carbon fiber remains, at present, a rather specialized and pricey material. It's of paramount importance, then, that its unique strengths are used in industries that can't afford to skimp on safety matters (space travel and the military for instance). Cost-effectiveness is always a factor to consider where carbon fiber is concerned, though.