Electromagnetic Railguns Explained: How Do They Work?

In 1873, James Clerk Maxwell's "A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism" touched on something very significant. "Conjectures of various kinds had been made as to the relation between magnetism and electricity," Maxwell wrote, going on to note that electric currents had been known to affect magnets but that there was much more to investigate about the connection between the two, though he could surely never have anticipated what the field of electromagnetism would have accomplished a century and a half later.

The principle and the technology are vital components of fluorescent lights, toasters, fans, and a myriad of other devices that are taken for granted by millions of people every day. It also powers vast and intimidating weapons like the enigmatic electromagnetic railgun.

Here's how electricity and magnetism combine to power high-velocity railguns, as well as the practical concerns that have forced some military powerhouses to largely abandon their pursuit of developing them.

How do electromagnetic railguns work?

Railguns are able to fire bullets at remarkable speeds — almost three times as fast on average, in fact, than standard guns. The former hits approximately 8,000 kmph or 5,500 mph while a typical gun manages 2,900 kmph or 1,800 mph at its fastest, Interesting Engineering notes.

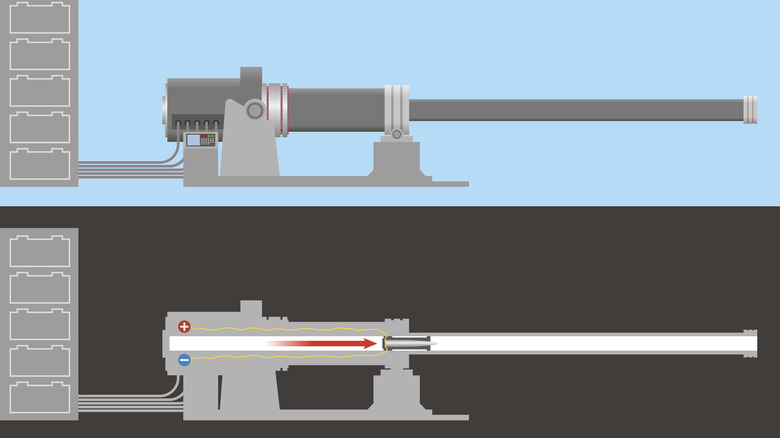

As the name suggests, railguns fire their shots from rails, which are made of electricity-conducting metal. One carries a positive charge and one a negative. The power supply passes between them, and as it does, a separate magnetic field is generated by each. The force generated acts on the "bullet," which is what launches it out of the railgun, according to How Stuff Works.

Railguns do have advantages in both speed and efficiency. Taking gunpowder out of the equation reduces some of the practical concerns and dangers surrounding typical ammunition. However, there are some crucial downsides to the use of railguns, which have prevented their becoming a military staple.

The trouble with railguns

Electromagnetic fields are at the heart of other crucial devices, like the marvelous MRI machine. One of the biggest issues, however, is quite predictable: they're notoriously power-hungry. While railguns can indeed far outstrip other firearms in the speed of their projectiles, in order to do so, they need to be incredibly large and provided with so much power that effective ways to utilize them are extremely limited.

Around one million amps, after all, doesn't come easily. In summer 2021, it was reported that the railgun the U.S. Navy had long coveted seemed to have been abandoned as an impracticality, with the advent of wider-reaching, less unwieldy missiles. Diverting power from a Naval vessel to fire and then rerouting it again afterward was the approach that had been taken to achieve the best results with railguns, but was unsustainable.

"Given fiscal constraints, combat system integration challenges and the prospective technology maturation of other weapon concepts, the Navy decided to pause research and development of the Electromagnetic Railgun [EMRG] at the end of 2021," the Navy said in a statement to Military.com.

The technology is certainly remarkable, but it appears to have been outstripped by other options.