The Most Bizarre Sponsors In The History Of F1

Formula 1 is well known for its sponsorship game. Max Verstappen's Formula 1 driver profile, for instance, includes a headshot of the driver in his racing uniform complete with 20 or more sponsor logos emblazoned across his body. Racing News 365 reported in February 2022 that Oracle had struck a deal with the Red Bull team to infuse between $75 million and $90 million annually into the team's budget for five seasons. In the process, the team will also adopt the Oracle moniker in its name: Becoming Oracle Red Bull on the grid. Even with a budgetary cap coming into effect, Formula 1 crashes, driver salaries, transportation and operational costs, and the research and development of the cars themselves demand an enormous volume of financial resources. Teams simply can't compete on a shoestring budget, which is why the likes of Hass and Williams remain at the bottom of the field year after year.

With financial backing being so overwhelmingly important for finding success on the track, it's no wonder why teams have entered into strange sponsorship deals in the past. From unwitting partnerships with swindlers to subversive messaging, some Formula 1 sponsors have been some of the most unique and bizarre in the history of the sport.

Eyetime, Lyoness, and myWorld

Starting with one of the strangest sponsorship arrangements, Formula 1 enthusiasts might be used to seeing one of many names for what is essentially the same business. According to BE Konflikt Management, a business that has routinely been a sponsor at Formula 1 events over the last few years is actually a pyramid scheme. The brand was founded in 2003 as Lyoness International AG. It has shown up as myWorld, Eyetime, Lyoness, Lyconet, and with other names. The brand has been drummed out of Norway for its illicit business practices and has been ordered to pay a fine of more than 3 million euros in Italy (almost $3.5 million). Still, this brand under a variety of different trading names continues to show up as a sponsor at Grand Prix events and even on Formula 1 cars.

Essentially what this business purports to do is offer users cash back on purchases. BE Konflikt Management notes that a user might be entitled to 3% or 5% cash back on their purchases, as long as they recruit enough new members to use the service as well. GrandPrix247 reports that Eyetime in particular appears to be masquerading as some sort of communications app to rival WhatsApp, WeChat, or Facebook Messenger. The CEO of this version of the entity has direct links to the parent company Lyoness, and the app itself remains an empty shell that doesn't do anything. It's odd then that the business would continue to throw money at F1 sponsorship opportunities in this new avenue without even a rough product to offer curious viewers.

Sugarbook

Sugarbook is a dating connection site where older, financially endowed men can meet younger women. Donut Media reports that Sugarbook was one of the 2018 title sponsors of the Singapore Grand Prix. The company was also slated to co-sponsor a party alongside Martini ahead of the event. Sugarbook and the relationships it fosters raise some concerns for many. The Plaid Zebra notes that dating within this environment doesn't raise an overt ethical dilemma because, at the core of these relationships, you'll find two consenting adults. This is certainly true, but the power dynamic created in the process makes it nearly impossible to decipher true attraction and enjoyment from simple 'usage' by one or both parties.

Because of this controversial status, Sugarbook is an odd choice for an event to partner up with. Onlookers may have mixed reactions to the inclusion of a morally gray brand and all that it stands for. There's certainly no judgment that should be levied against the people who utilize this and other platforms that connect like-minded individuals, but that doesn't take away from the gaucherie of the choice by Formula 1.

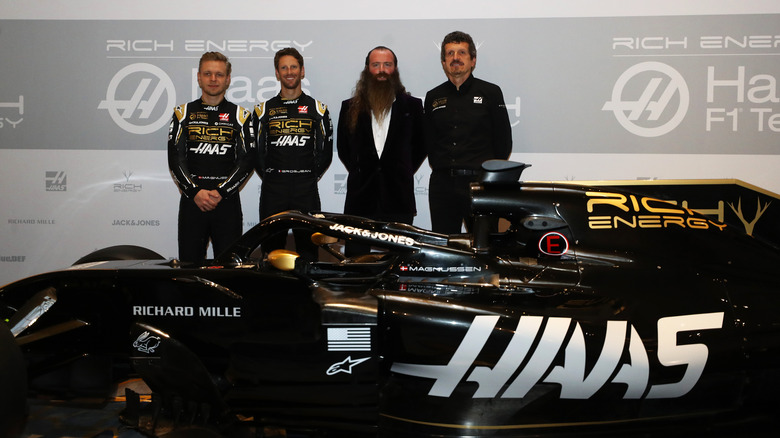

Rich Energy

Certainly another wild story, the Rich Energy fiasco, will surely go down as one of the strangest sponsorship deals in the sport. ESPN reports that the entirety of Formula 1 interactions between Haas (and other teams) and Rich Energy have been strange and somewhat contentious, to say the least. There had been questions surrounding the legitimacy of the product when Rich Energy came into the fold in 2019, and in court, the outfit had been ordered to remove the antler logo from its marketing efforts because it had been lifted almost directly from another company. Shortly after, it came out that Rich Energy's CEO William Storey had tried to buy out Force India as it was headed into arbitration, and then backed out of a sponsorship deal with Williams at the last minute (literally leaving Claire Williams waiting in an Austin restaurant) days before announcing the Haas partnership.

Donut Media also reports that in the midst of all this, Haas never received the sponsorship money promised in the agreement, and eventually Storey would simply Tweet out that the company had terminated its deal with the team. This was apparently happening as Storey was being ousted from the company, and didn't reflect the actual facts on the ground. Nevertheless, with a rogue partner that had hijacked Haas' trademark vehicle livery and continuously failed to hold up its end of the agreement, the team was forced to move on.

Mission Winnow

Mission Winnow appeared prominently emblazoned on the tailfins of the Ferrari cars at the start of the 2019 season. The brand was featured in one of the most easily spotted areas of a Formula 1 Grand Prix, but the mission of the company itself is quite hazy. The company's homepage tells visitors that Mission Winnow is "committed to constant improvement," and is a "change lab focused on reframing conversations, sparking open debate," and more. Jalopnik reports on the brand with a bit more clarity, noting that Mission Winnow is essentially a front for Phillip Morris International. More specifically, it acts as a stand-in for the conglomerate's most notable subsidy: Marlboro.

Mission Winnow is stylized in a strange manner, to say the least. But if you refocus on the car as a whole rather than the logo itself, you might just make out the faint resemblance to a Marlboro package. The brand's nameplate on the tail attempts to replicate its logo, which is a faithful adaptation of the Marlboro branding imagery turned on its side. Mission Winnow was designed to skirt around the rules banning tobacco advertising in Formula 1 (which came into effect in 2006, according to Jalopnik). AutoSport notes that even with this circumvention while driving in Australia, the branding must be removed from the Ferrari cars because of the association alone. McLaren's tobacco-adjacent sponsor, A Better Tomorrow, was faced with the same decision ahead of the 2019 Melbourne Grand Prix.

T-Minus

The last entry is perhaps the most bizarre! T-Minus was a brand introduced to Formula 1 through the now-defunct Arrows team in 1999. It initially claimed to be an energy drink, then a motorcycle brand, and then it bounced around as a few other things before it finally became clear that the business was simply a rebranding tool (via Donut Media). Headed by Prince Malik Ado Ibrahim, T-Minus agrees to add $125 million to Arrows' coffers, and the man behind the brand was often seen at press events and in the paddock on race days.

According to Crash, instead of selling anything itself, the idea was to place a logo on a Formula 1 car, then sell this brand name as a collaboration vehicle to increase market visibility for other companies. The partnerships never really amounted to anything, and the Arrows team eventually died out when its benefactor receded without infusing the team with its promised funding. Donut Media also notes that the faux-investor later arrived on the NASCAR scene in 2005. Under the corporate brand Maverick Motorsports, the swindler allegedly stole close to $1 million from Robert Richardson Sr., the father of Robert Richardson Jr., a Busch Series driver that the company was supposed to be sponsoring (via McKinney Courier-Gazette).