The Incredible Story Of Pepsi's Harrier Jet Giveaway

None of us are immune to the effects of advertising. Whether we like it or not, we're lovin' it, we're just doing it, and we're eating candy bars to manage our anger. A company will go to great lengths to gain more market share, and that's especially true when they find themselves in the midst of an ongoing culture war for the hearts and refrigerator space of people everywhere.

Coca-Cola and Pepsi-Cola have been locked in such a battle for more than a century. In that time, both companies have tried everything from changing their signature formula to blind taste tests to prove once and for all who's the King of Cola. For much of that time, Pepsi has played second fiddle to the giant that is Coca-Cola. "Is Pepsi okay?" must be among the most common phrases uttered in restaurants everywhere.

Then, in the mid-1990s, some ambiguous advertising and a college student with a plan resulted in one of the weirdest moments of the Cola Wars. By the end, Pepsi was locked in a legal battle against one man in a fight over ownership of a high-tech military aircraft.

Pepsi Points

In 1996, Pepsi announced a new promotional campaign called Pepsi Stuff. Consumers could collect points from the packaging of specially marked Pepsi products and redeem them for merchandise, most of which was emblazoned with the Pepsi logo. Consumers would literally cut the points from the packaging of 2-liters and 12-packs, and mail them in with an order form in exchange for t-shirts, hats, and mountain bikes.

Today, these sorts of reward programs are ubiquitous, but they were comparatively revolutionary at the time. According to The New York Times, Pepsi modeled its Pepsi Stuff campaign on Philip Morris' Marlboro Gear program. The estimated cost of the Pepsi Stuff program was $200 million, which included an estimated $125 million in merchandise consumers could acquire. Pepsi called it the largest promotional campaign in the company's history, at the time.

The program practically begged to be gamed. Almost immediately, consumers started crunching the numbers on the best Pepsi products to buy in order to maximize the number of points they could get. People got so good at claiming prizes that Pepsi cut the promotion short. According to The Wall Street Journal, the redemption rate was about 50% higher than the company anticipated, causing problems both for Pepsi and for bottlers, who split the cost of prizes.

The commercial

To get the Pepsi Stuff program off the ground, the company went on a marketing stint, releasing commercials advertising the rewards program. One commercial showed a teenager in possession of various prizes all earned with Pepsi Points. First, he's seen wearing a Pepsi-branded t-shirt. Next, he's wearing a Pepsi-branded leather jacket. Then, as he exits his home, he slides on a pair of sunglasses. As each prize product appears, its name is projected onscreen along with a corresponding Pepsi Points value. The t-shirt will cost you 75 points, the leather jacket costs 1,450 points, and the sunglasses are 175.

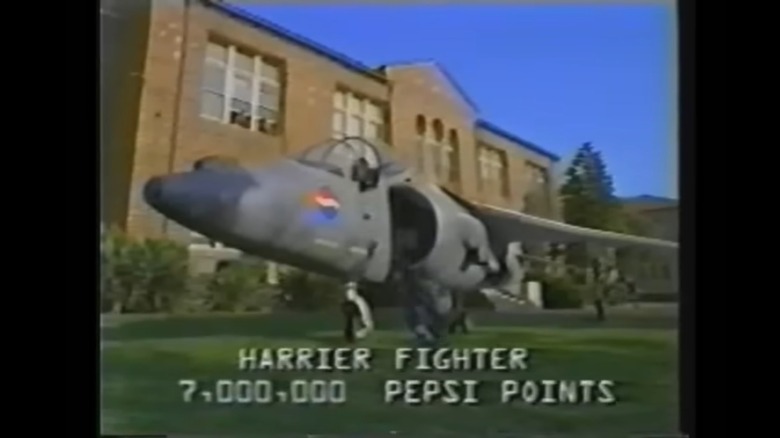

The commercial cuts to a group of kids looking at a Pepsi Stuff catalog as a shadow passes overhead and a burst of wind floods through an open window and scatters papers in a classroom. Then a Harrier jet slowly descends onto the schoolyard lawn, revealing the kid from before in the pilot's seat. As he steps out of the jet and onto the lawn, two lines of text appear on the screen: Harrier fighter, 7,000,000 Pepsi Points. The kid walks away from the jet (suspiciously away from the school entrance) and the Pepsi Stuff tagline fades onto the screen. "Drink Pepsi Get Stuff." The implication seemed clear: Buy enough Pepsi and you could get your own jet. At least, that was the interpretation of one man.

John Leonard

The '90s were an era obsessed with everything extreme and the Harrier jet at the end of the commercial was an example of that. At the time, companies were taking every opportunity to make their products feel flashier, more exciting, and cool. When all else fails, put a jet on it. Most people understood the commercial the way Pepsi claims to have intended it, as a fanciful expression designed to drive excitement for the Pepsi Stuff program, and nothing more. Then there was John Leonard.

As reported by the AV Club, Leonard was a college student when the Pepsi Stuff commercial aired, and he immediately saw an opportunity. Harrier jets were valued in excess of $20 million at the time, some estimates even place them over $30 million apiece, well beyond the grasp of the average person. But the Pepsi Stuff promotion, if the advertisement was to be believed, offered the chance to own the jewel of the United States military's air presence for a fraction of the cost.

Even some quick back-of-the-napkin math reveals that acquiring 7 million Pepsi Points would cost considerably less than buying a jet outright. The only trouble was that Pepsi Stuff was a limited-time offering, so Leonard would have to act fast to earn the points and acquire his jet.

The quest for points

With his goal firmly affixed in his mind, Leonard began crunching the numbers on the points he needed. At the time, each 12-pack of Pepsi was worth five Pepsi Points. To get the requisite 7 million points, Leonard would have to buy 1.4 million packs at an estimated cost of over $4 million. That's a lot of money, and a lot of Pepsi, but once Leonard had his jet, he'd have earned about $20 million on his investment, give or take a few million.

Of course, that would leave Leonard with 16,800,000 cans of Pepsi to consume. That's enough that he could drink an entire 12-pack every single day for the next 3,800 years and he'd still have half a lifetime's worth left over. If Leonard stacked all of those boxes together, they would form a cube roughly 83 feet on a side and they would weigh about 14 million pounds, roughly the same as a herd of 1,000 African bush elephants (via World Wildlife Fund).

The logistics alone — getting the funding to buy all that Pepsi and finding a way to store it and offload it later — might have been enough to turn Leonard off from the whole scheme, until he gave the Pepsi Stuff rules another look through.

The loophole

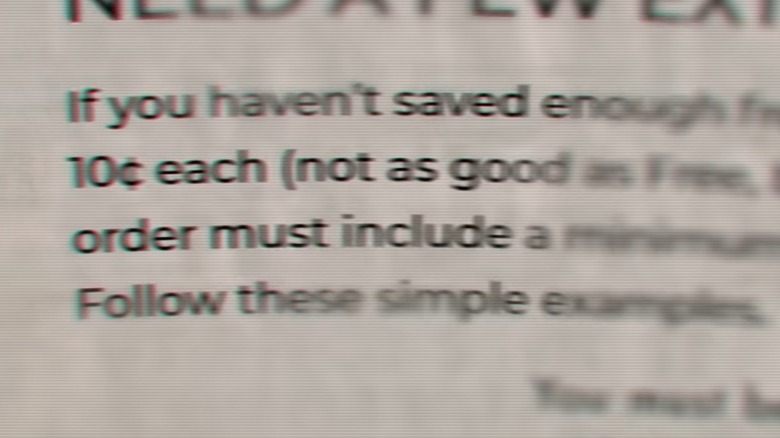

It turned out, all of the planning and logistics weren't going to be necessary at all because consumers didn't actually have to earn all of their Pepsi Points by buying Pepsi products. When Leonard looked at the back of the order form, he found some fine print that simplified the entire process. The rules of the Pepsi Stuff program stated that as long as a consumer turned in 15 points gained from actual Pepsi products, any additional points could be purchased from Pepsi for $0.10 each.

That meant all Leonard had to do was purchase three 12-packs (or some other equivalent amount of Pepsi products), then turn those 15 points in along with a check for $699,998.50 plus a shipping fee to purchase the remaining points needed to get to the advertised 7 million point cost of the Harrier jet.

It's unlikely that Pepsi expected anyone to take the advertisement seriously and try to collect. For an ordinary consumer, the point purchase process meant you could turn in 15 points along with $6 for a t-shirt or $143.50 for a leather jacket, but Leonard didn't want those. He wanted a jet. He filled out an order form requesting the jet, accompanied by 15 actual Pepsi Points and a check for the remaining required points, and waited for his combat aircraft to descend onto his driveway.

Pepsi's response

As reported by The Hustle, Leonard received a response from Pepsi a few weeks after he made his request. That response did not come in the form of a complex airborne weapon of war. Instead, Leonard received a letter stating in no uncertain terms that the Harrier jet was not a part of the Pepsi Stuff promotion, despite its inclusion in the marketing materials.

The company referred back to the official Pepsi Stuff catalog and associated order form, neither of which included a Harrier jet — or any aircraft of any kind, for that matter. The closest thing was a mountain bike, valued at 3,300 points.

Pepsi maintained that the jet's inclusion in the commercial was intended to be humorous and not meant to imply an actual offer. The company returned Leonard's check along with the letter and a handful of coupons for free Pepsi by way of apology for any confusion. The story might have ended there, but Leonard was determined to acquire the jet he perceived to have been promised. According to the Hustle, Leonard got a lawyer and sent another letter, this time demanding the Harrier jet as promised within 10 business days. Suffice it to say, Pepsi didn't deliver.

The court case

Leonard had two choices. He could chalk it up to a bit of fun that didn't pay off, or he could fight the soda giant in court. He chose the latter. On August 6, 1996, Leonard brought a case against PepsiCo. In the suit, Leonard insisted that the commercial was a legitimate offer and that he had completed his obligation to Pepsi as laid out in the Pepsi Stuff rules. For its part, Pepsi maintained that no reasonable person would believe the commercial constituted a real offer (via Justia).

Considering that the advertisement and whether or not it amounted to a real offer was the heart of the debate, the case documents outline the events of the commercial in minute detail. The court documents also included another response received by Leonard, not from Pepsi but from the advertising company the company hired to make the commercial. That letter states, "I find it hard to believe that you are of the opinion that the Pepsi Stuff commercial ('Commercial') really offers a new Harrier Jet. The use of the Jet was clearly a joke that was meant to make the Commercial more humorous and entertaining. In my opinion, no reasonable person would agree with your analysis of the Commercial." The only remaining question was whether or not a judge would agree.

The ruling

The case bounced around for more than a year before coming to a close. Rather than go to trial, Pepsi moved for summary judgement, essentially stating that a trial wasn't necessary because there was no offer made and thus nothing to try.

In the end, the judge agreed. The question at hand was whether the advertisement was an offer in and of itself, or simply a solicitation to receive an offer. If it was an offer, then the last action needed to complete the transaction was Leonard sending in an order form. If it was a solicitation for offers, then the last step was for Pepsi to accept Leonard's order form, which they did not do. According to Justia, the judge sided with the second interpretation and the case was dismissed. That judgement came down to a few key facts. The judge stated that the commercial was not an offer of goods, that there was no fraud because a commercial is not a contract, and that no reasonable person would believe that a jet was really being offered.

Initially, not only did Leonard not get the jet he wanted, but he was also ordered to pay more than $88,000 in legal fees to Pepsi. Leonard didn't pay and, ultimately, Pepsi withdrew their claim to recover the legal fees.

The appeal

In the spring of 2000, Leonard took the case to appeal — but that second day in court went about as well as the first. Three judges from the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit took arguments on March 21 and rendered a decision on April 17, 2000, according to Justia.

The appeals court briefly summarized the case in question. The whole court document from beginning to end is little more than three paragraphs, outlining a short synopsis of the ad, Leonard's attempt to cash in on the offer of a jet, and the previous judgement ruling against Leonard. The judges end their decision with a single definitive sentence. It reads, "We affirm for substantially the reasons stated in Judge Wood's opinion."

With those 11 simple words, the appeals court delivered a feeble conclusion to a saga that had become the stuff of legend. Despite our schoolyard urban legends, we did not live in a world in which an enterprising everyman could trade cleverness and perseverance for incredible prizes. John Leonard would not be getting his jet.

The new fine print

Pepsi won the day in court, but that ruling was based largely on whether a reasonable person would interpret the commercial as having actually offered a real Harrier jet. One might imagine a scenario in which countless others followed in Leonard's footsteps in an attempt to outfit an entire fleet of civilian-owned hovering aircraft. While that outcome was unlikely, Pepsi took steps to ensure it couldn't happen.

Leonard's attempt to game his way into a fighter jet prompted Pepsi to make a couple of slight modifications to the Pepsi Stuff commercial. In this new version, most of the commercial played out the same way, but if you watched closely at the end, you might have noticed a couple of subtle but important changes.

First, the point value listed for the Harrier was changed from 7 million to 700 million and the words "Just kidding" now appeared beneath the point value. The postscript made it clear that the jet was a joke, but even if it weren't, getting a Harrier with Pepsi Points was now a losing investment. Changing the point total raised the cost of buying enough points from $700,000 up to $70 million, more than the actual cost of buying a brand new Harrier outright.

The documentary

This story has everything: a battle between an ordinary individual and a powerful corporation, a get-rich-quick scheme, a loophole, a plot twist, and a seemingly endless supply of flavored, carbonated sugar water. The drama inherent in the relationship between Leonard and Pepsi, coupled with a growing nostalgia for the 1990s, almost begs for a detailed documentary investigation and it's about to get one.

A new documentary directed by Andrew Renzi, prior director of Hulu's "The Curse of Von Dutch," the story of the well-known brand of trucker hats, will get into the details of Pepsi Stuff, the Harrier jet, and John Leonard in four parts. According to Indiewire, the documentary includes interviews with Leonard, his collaborators, and Pepsi executives from the time of the contest. It also utilizes actors to re-enact key moments in the story.

While the documentary is likely to get people talking, and maybe even buying more Pepsi, it's unlikely to get Leonard any closer to his Harrier dreams. Maybe he'll have another opportunity in the future though, since Pepsi has revived the Pepsi Stuff program in various formats since the '90s. It's probably only a matter of time before the soda giant brings it back again. If it does, be ready with your calculators, a certified check, and a good lawyer. The Netflix documentary "Pepsi, Where's My Jet?" premieres November 17, 2022.