Uber's San Francisco Driverless Tests Prompt DMV Ultimatum

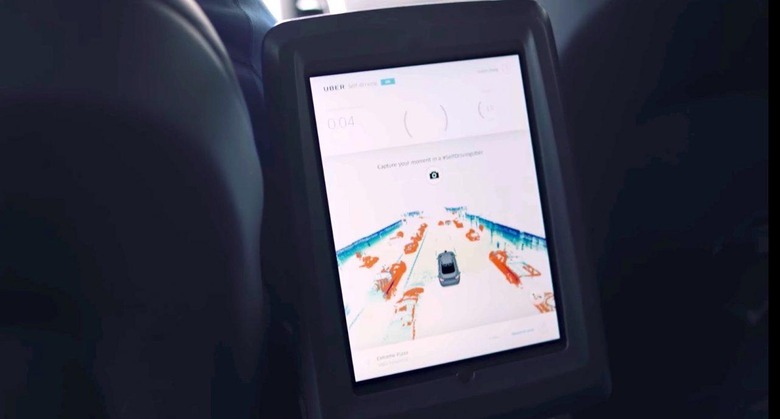

Uber's decision to roll out self-driving cars in San Francisco this week has gone down like an autonomous lead balloon with regulators, angry the firm didn't apply for permits like others running trials. The ride-sharing company confirmed today that, not only will it set loose a fleet of Volvo XC90 SUVs outfitted with the latest fruits of its autonomous research, but that it didn't feel it needed special permission to do so. That comes down to a loophole in the rules which Uber feels it can exploit.

In a company blog post, Anthony Levandowski, Head of the Advanced Technology Group at Uber, said that the company is aware "that there is a debate over whether or not we need a testing permit to launch self-driving Ubers in San Francisco." Currently, twenty manufacturers have received such permits from the California DMV. "We have looked at this issue carefully and we don't believe we do," Levandowski argues.

The primary argument is one of semantics, it seems. According to Levandowski, "the rules apply to cars that can drive without someone controlling or monitoring them" and yet "our cars are not yet ready to drive without a person monitoring them." Indeed, the XC90 fleet each has a human driver sat behind the wheel, ready to take over should the systems struggle.

Uber's argument highlights one of the perennial issues facing regulators and researchers alike around self-driving vehicles. From the ride-sharing company's perspective, its human drivers are "monitoring" a self-driving car that isn't yet properly autonomous. Unsurprisingly, the California DMV doesn't see things the same way.

"Twenty manufacturers have already obtained permits to test hundreds of cars on California roads," a spokesperson told the FT. "Uber shall do the same."

Other companies working on autonomous cars, and speaking on the condition of anonymity to the newspaper, accused Uber of trying to avoid disclosure requirements that would ordinarily be an integral part of driverless testing. According to the DMV, notification must be made within ten days of any accident taking place involving an autonomous vehicle, even if the vehicle itself was not at fault. Annually, license holders must release a so-called "disengagement report" detailing the disengagements of the technology during their testing.

According to Uber's Levandowski, no collisions involving its driverless car had occurred in California. However, the division chief told the FT that he was unclear on whether the company planned to release any collision data given that it would be considered "proprietary information." One of Uber's goals seems to be forcing California's hand to be more open to driverless trials.

"Most states see the potential benefits, especially when it comes to road safety," Levandowski wrote in his post. "And several cities and states have recognized that complex rules and requirements could have the unintended consequence of slowing innovation ... Our hope is that California, our home state and a leader in much of the world's dynamism, will take a similar view."

Whether safety regulators will see things in quite the same way – or, indeed, react positively to Uber's boundary-pushing tactics – remains to be seen. Autonomous car projects looking to take shortcuts to market have struggled in the face of regulator reticence; most recently Comma.ai cancelled its retrofit self-driving tech plans after facing greater scrutiny on sa