Those TSA Scanners Were Literally Only Good For Seeing You Naked

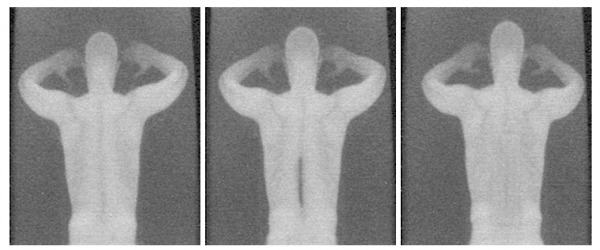

The full-body X-ray scanners only retired last year amid long-standing concerns that they intruded on privacy by showing travelers naked were also riddled with security loopholes, new research claims. The TSA used the Rapiscan Secure 1000 scanner between 2009 and 2013 in airports across the US, but computer scientists have demonstrated that with a little preparation the machine could miss knives, guns, and even explosives from being smuggled onto planes.

Some of the methods that successfully disguised such contraband were surprisingly low-tech. For instance, by carefully placing a weapon in such a place on the body – either by taping it at the right orientation, or stitching it into clothing – the typical front and back scans the TSA had been performing could have missed it against a dark background.

A gun taped to the outside of a leg, for instance, proved almost impossible to locate on the final scan.

Meanwhile, covering knives or explosive packages with teflon tape left them reflecting X-rays with the same intensity that flesh does, effectively making them invisible if placed on the right spot of the body.

Molding plastic explosives to fit the contours of the body proved to be another method by which the scanners – and their human operators – could be fooled.

The TSA only ceased using the Rapiscan technology last year, when complaints about privacy reached levels too great to ignore. Instead, travelers are now expected to pass through less intrusive machines, though potentially then be subjected to so-called "enhanced pat-downs" during which time TSA agents perform a physical search of the body.

Retired Rapiscan machines, meanwhile, were repurposed in government facilities, including jails and courthouses.

The team – which included faculty members, graduate students, and others from the University of California, San Diego; the University of Michigan; and the Department of Computer Science in Johns Hopkins' Whiting School of Engineering – blames some of the susceptibility to hacks on faulty assumptions by Rapiscan Systems itself.

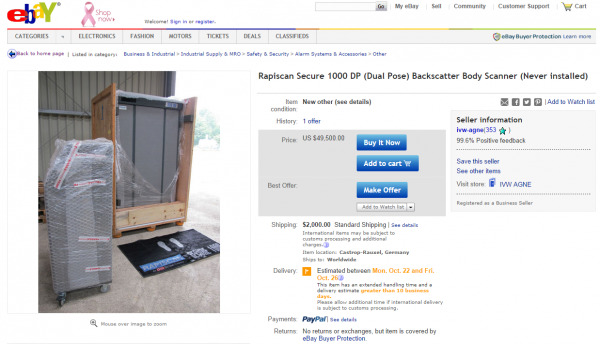

For instance, the company had worked on the idea that those with nefarious intentions wouldn't have access to the scanner hardware and software in order to identify any shortcomings. However, the research team was able to buy a surplus Secure 1000 on eBay in 2012, and then reverse-engineer the software.

Through that process, they were then able to refine their exploits based on what the scanner actually picked up.

"Frankly, we were shocked by what we found," University of Michigan computer science professor Alex Halderman concluded. "A clever attacker can smuggle contraband past the machines using surprisingly low-tech techniques."

Ironically, TSA operatives are probably the last to be surprised by the new research, which will be presented at the USENIX Security conference today. A former agent admitted earlier this year that the failings of the Rapiscan system were well known.

"The only thing more absurd than how poorly the full-body scanners performed," Jason Harrington said of the $150,000 apiece machines, "was the incredible amount of time the machines wasted for everyone."

The researchers notified Rapiscan and the US government several months ago regarding their findings, and have already made suggestions how the exploits could be mitigated, at least partially.

VIA Johns Hopkins

SOURCE Security Analysis