The Weird Thing About EPA Car Testing

You'd think it would be straightforward: a new car gets launched, it gets a set of official economy figures from the EPA, and then you can make a measured comparison before you head to the dealerships. In reality, though, economy testing from the US Environmental Protection Agency isn't quite what most people shopping for a new car might expect it to be.

EPA myth: The agency tests every car

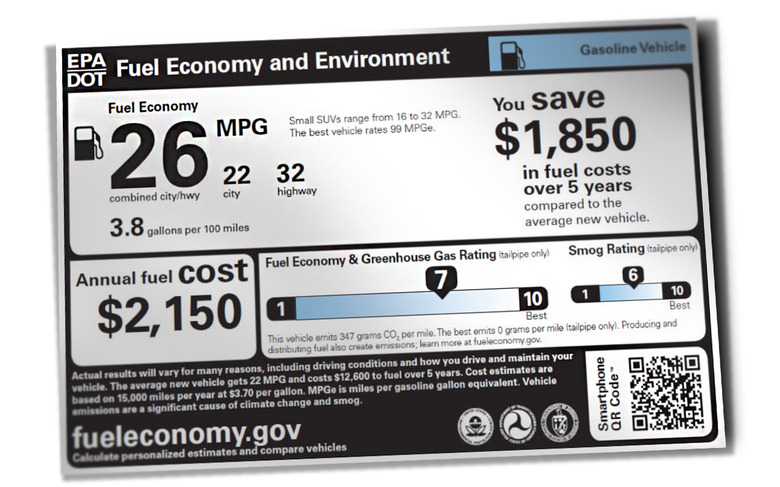

Perhaps the biggest misconception about what the EPA does is that the agency itself tests every new vehicle launched. You'd certainly be forgiven for assuming that: after all, it says "EPA" on the automaker websites and on the Monroney sticker each new car sold in the US must display on the window.

In reality, though, the EPA simply doesn't have the resources to do all that testing itself. In 2019, for example, there were almost forty new car models offered in the US; most of those have multiple engine options. Factor in new and tweaked engines for the 250+ existing models on sale that year too, and the scale of the challenge starts to become clear.

Instead the EPA makes the automakers themselves do it. They in turn typically look to independent labs to test out the city and highway performance of their cars, and come up with the necessary figures. Those are then supplied to the EPA.

To keep everyone fair, the EPA picks a selection of those vehicles to test itself at its National Vehicle and Fuel Emissions Laboratory in Ann Arbor, Michigan. For model year 2020 cars, for example, the EPA ran about a tenth of the number of tests overall compared to manufacturers (it's worth noting that some cars get multiple tests, both by the EPA and by manufacturers). For each model year, all the way back to 1982, it releases a big spreadsheet showing what it tested and what relied on automaker tests alone.

How, exactly, the EPA decides which cars to test itself is unclear. After all, if manufacturers knew the criteria, they might be able to game the system more easily. With big-ticket purchase decisions often based – at least in part – on MPG figures (or range numbers for electric cars) there's a real incentive for manufacturers to make sure their models perform well.

EPA myth: The standard test reflects how everybody drives

No two drivers are the same at the wheel, and that's a problem when you want to boil vehicle efficiency down to a single number. Even when broken out into city and highway driving, two figures are going to struggle to encapsulate the whole range of driving styles.

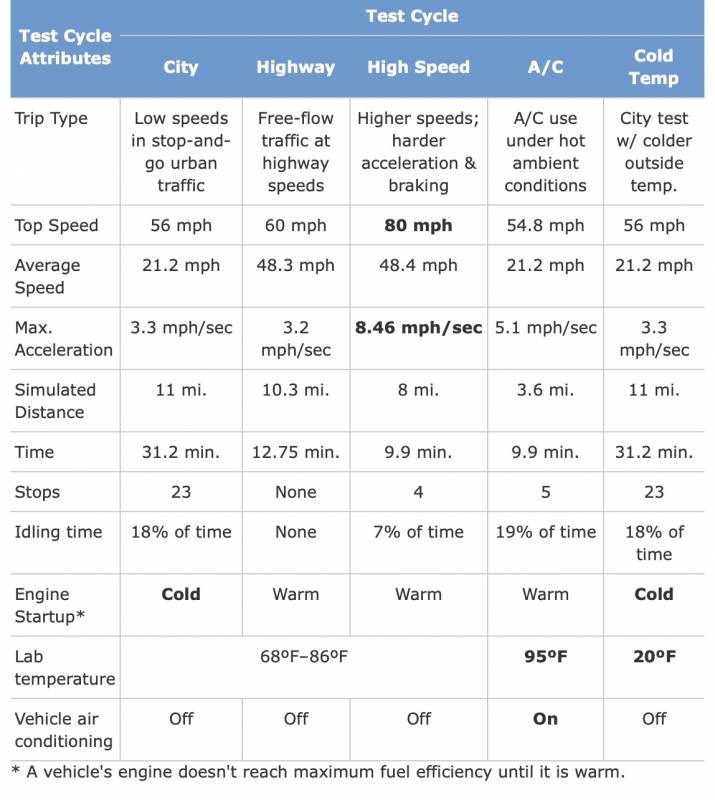

The EPA has settled on a set of standardized driving routines, or cycles, which it uses to figure out those numbers. Up until MY2007 vehicles there were just two such cycles: one for city, another for highway. From MY2008 vehicles on, it added air conditioning, cold temperature, and high speed test cycles, which it uses to adjust the highway and city numbers to try to take into account differences in driving style and conditions.

The city cycle, for example, is designed to replicate the sort of low speed, stop-and-go driving you might do in an urban area. That means no driving faster than 56 mph, and an average speed of 21.2 mph. Maximum acceleration is 3.3 mph/sec, and the test lasts for a simulated 11 miles with 23 stops. Other factors control engine temperature, idling time, and other criteria.

For the highway cycle, in contrast, the top speed lifts to 60 mph and average speed to 48.3 mph. Maximum acceleration is trimmed a little, to 3.2 mph/sec, and there are no stops. The engine starts out warm, too, rather than cold, which makes it more efficient.

60 mph on the highway hardly seems representative for many of us, and the EPA clearly agreed. The High Speed cycle is intended to model that better, lifting maximum speed to 80 mph (though average speed only nudges up to 48.4 mph). The big difference is maximum acceleration, which rises to 8.46 mph/sec; there are 4 stops, and less idling.

Neither the EPA nor automakers go out onto public roads and try to maintain a 48.4 mph average speed. Instead, the tests take place in strictly controlled environments: the car is put on a dynamometer, which basically means one or two large rollers, connected to an electric motor. Those rollers then simulate the speed and resistance of an actual road, while the necessary measurements are taken.

Even with all the various factors combined, it's not hard to see that the way most of us drive isn't going to necessarily match up to the way the EPA envisages driving. That's been particularly borne out with recent EV tests: Porsche had been expecting its Taycan electric luxury sedan to get in the region of 270 miles on a charge, but the EPA rated it at just over 200 miles.

Porsche brought out its own test numbers to show the discrepancy, but at the end of the day it's the EPA figures that are listed – and the ones that potential electric car drivers will compare with rivals from Tesla and other brands.

EPA myth: Global cars don't mean global results

Adding the confusion, a vehicle's MPG or range in the US almost certainly won't line up with its MPG or range in other countries. That's because, just as the US has its own testing cycles, so too do other geographies. It means that what may look like exactly the same car can get some very different economy numbers.

Probably the best-known is the WLTP (world harmonized light-duty vehicles test procedure). It replaced the NEDC (new European driving cycle) procedure in Europe from the end of 2019, after regulators tried to update the tests to better reflect modern driving styles. The goal may be similar, but the results can vary significantly compared to the EPA's figures.

That usually has the biggest impact when a new model is announced in Europe, complete with economy or range stats based on WLTP testing (or provisional testing). Since the tests aren't like-for-like, you can't assume that an EV rated for 300 miles of all-electric driving in Europe will also be rated for the same in the US.

Take the Porsche Taycan Turbo for example. In the US, the EPA rates that as capable of 201 miles of total range. Porsche's independent testing in the US, meanwhile, suggested a 275 mile figure for total range (mixed city/highway) was more accurate. In Europe, on the WLTP cycle, the same car is rated for 237-280 miles. Typically, WLTP testing is more generous to range and fuel economy than the EPA numbers turn out to be.

Will Taycan Turbo owners see anything like those numbers in their own driving? That's the million dollar question, and it's what makes vehicle economy so difficult to calculate and compare. Regardless of the test cycle being used, if the way you drive isn't reflected in the criteria the testers rely on, it should come as no surprise that your real-world experience doesn't match up.