The Reason Why The First-Ever Black Hole Photo Was Such A Big Deal

During April 2017, the Event Horizon Telescope project turned eight satellites towards a point in space. Scientists were trying to take a photo that would confirm years of speculation and theorizing. They were taking a picture of the now famous black hole at the centre of the Virgo A galaxy Messier 87.

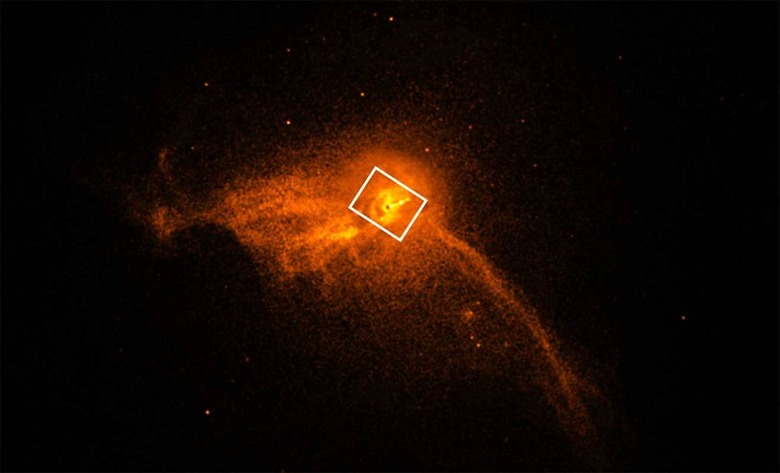

Released on 10 April 2019, the blurred image of a ring of bright orange shed light one of the biggest mysteries of our time. A miracle of technology, data-recording and timing has brought us our first glimpse of a concept that was previously the work of science-fiction.

All this talk, but what does this new discovery mean for us and science as we know it? And why is everyone getting so excited over it?

An answer after a century of speculation

Finally, we have an answer. Speculation about black holes dates to the early 1900s, when we discovered that light can be warped with fluctuations in gravity. This realization led physicists to theorize that there could be objects in space that have masses and densities so immense that even light, the fastest speed known to man, is trapped in its pull.

Albert Einstein's theory of relativity claims that as all this energy gets sucked in, it reaches a point at its centre where density reaches an infinite value, creating a gravitational pull nothing can resist. All light and objects are trapped here and can no longer be seen. They call this point the event horizon – the black hole at the centre of the orange loop.

While it all sounds insane, observations made of events that occurred in space would only make sense with Einstein's framework. Scientists have seen dust clouds and stars interacting with massive gravity waves that they logically assumed would be a black hole. Stars would make loops around an invisible point and slingshot off at great speeds. There are plenty of images of light matter collected around a point suspected to be a black hole, but we've never been able to gaze at its core – the event horizon itself, which would put any doubt to rest.

Miracle of circumstance and technology

Another reason why this was such a big deal was how rare it was for the stars to literally align for an image like this to be taken.

For years, scientists have tried to take a picture of the black hole in our own solar system the Milky Way. It would make sense; The Sagittarius A* black hole in our system much nearer and we've seen indirect evidence that the theorised event horizon would exist.

But it's not been easy as because of its proximity to Earth, it doesn't "keep still" for the shot. We could only get images of events and matter around the supposed black hole.

The image we got in the end, of the Messier 87 black hole in the galaxy Virgo A, is far enough that it is more stationary in the sky. Being 55 million light-years away, it makes it possible for scientists to get a mugshot straight down the middle.

With that said, it wasn't just a point-and-shoot. It was several years' work, utilizing satellites from all over the globe. In short, eight telescopes from around the world pointed at Virgo A and combined their observations together to piece together the image we have today. The image files on each satellite were roughly 350 terabytes a day. They couldn't be transferred over, but instead flown over to have the images assembled.

No wonder the EHT project team called this an "Earth-sized telescope."

Now what?

The image will help astrophysicists sleep better at night knowing the theory they've been banking on for years is once again validated, and then some. One of the core pillars of science today, it would be devastating should we have found out Einstein was wrong. The great scientist's equations predicted there would be a perfect circle and we now have hard evidence.

Beyond a good night's sleep, the image helps scientists to get a better estimate of the precise mass of the black hole. Before last week, they only had images of events around the hole to make guesses. The Virgo A black hole is estimated to be 6.5 billion times the mass of our sun. To put this in perspective, the sun is 330,000 times the mass of Earth. That's a lot of zeroes.

This knowledge puts scientists in a better position to make analyses and approximations of black holes and other events in the universe.

The discovery may not blow the minds of many of us who've grown up with science-fiction films the likes of Doctor Who and Interstellar. But it's certainly a triumphant moment and an encouraging testament to our thirst for discovery.