SETI Sheds Light On Neptune's 7th Moon

At last, research has shown significant data on a 7th moon of Neptune, a planet that until now only really had 6 moons of which to speak. While scientists have had the images needed to see the seventh moon of Neptune since all the way back in the year 2004, it was only in 2013 that science had access to so-called "specialized image analysis" required to detect the 7th moon. So tell all your science teachers, tell all your friends: it's time to update your space maps again.

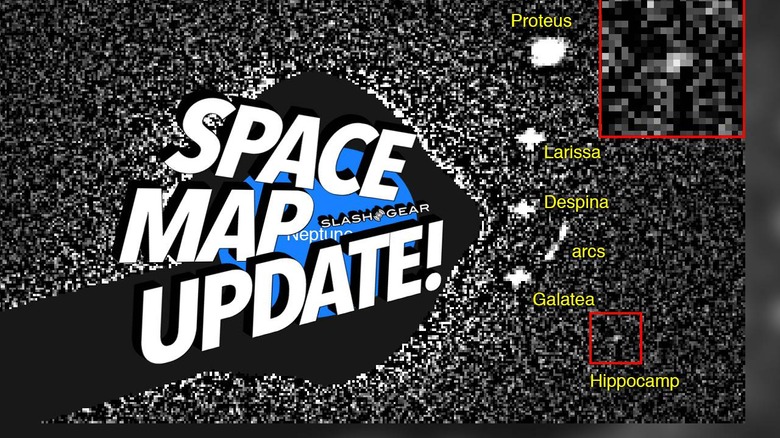

In the image above, straight from researcher and scientist and astronomer Mark R. Showalter from the SETI Institute, we see the full hand. This is officially the earliest (yet) known image of the newest moon discovered. That new moon is very, very tiny, and it's name is Hippocamp. This image was captured by the Hubble Space Telescope in the year 2004.

Something is very strange about this moon – it's apparently known in astronomer circles as "the moon that shouldn't be there." (You've gotta be a really cool astronomer to be cool enough to make a nickname like that, we heard it from a different report over at SETI this week. The moon shouldn't be there because its living in the presence of a significantly larger moon.

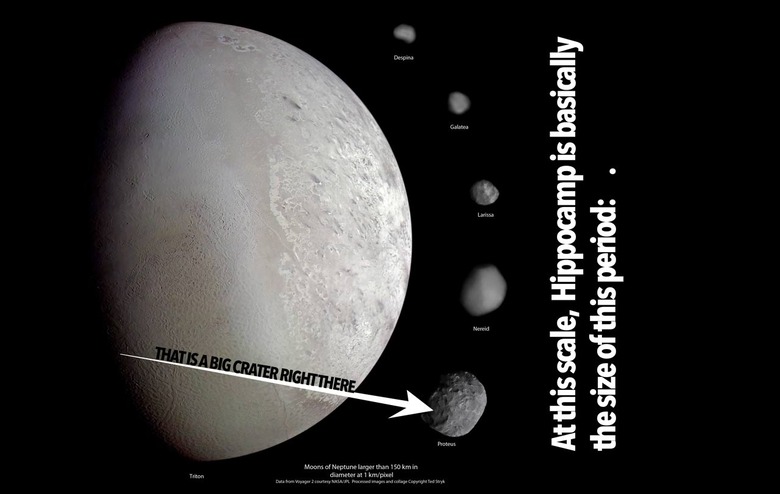

It would seem that this much smaller moon might well be a chunk. A chip off the ol' block. A hunk of the second-largest moon in the bunch, Proteus. Hippocamp is approximately 20-miles (34km) across. It's got a mean radius of approximately 17 kilometers – it's very, very small. Hippocamp is the smallest moon in the Neptune moon group.

Annotated movie of Hippocamp with Proteus from SETI on Vimeo.

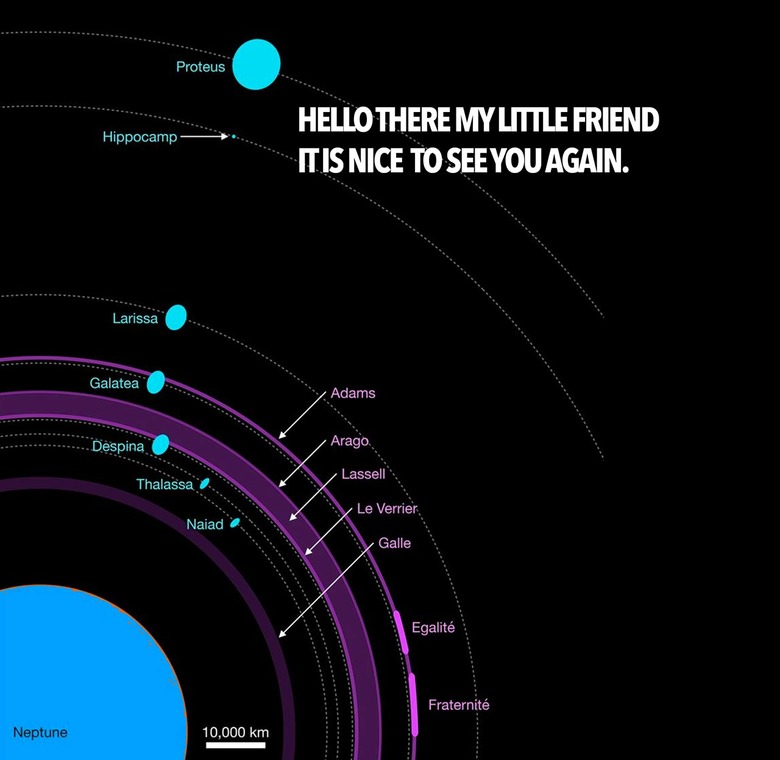

It would appear that the orbital semimajor axes of the second-largest and smallest moons hanging out around Neptune are different by just 10%. Evidence shows a migration of Proteus that indicates it was once orbiting Neptune in approximately the same orbit at which Hippocamp now exists. Best of all the evidence of possible smashing of Proteus to pieces is a set of images from Voyager 2 from 1989 which show a significant impact crater on Proteus.

"In 1989, we thought the crater was the end of the story," said Showalter. "With Hubble, now we know that a little piece of Proteus got left behind and we see it today as Hippocamp."

Above you'll see the relative sizes of the various moons of Neptune as calculated and processed by Ted Stryk. The original listing can be found over at The Planetary Society right this minute. Original image data was captured on or about August 25, 1989, processing far more recently.

For more information on the subject matter above, head over to the strikingly well-titled paper "The seventh inner moon of Neptune" in the scientific publication Nature. With DOI:10.1038/s41586-019-0909-9 this paper was authored by M.R. Showalter, I. de Pater, J.J. Lissauer, and R.S. French.