There's Bad News For This Nearby Exoplanet We Hoped Was Habitable

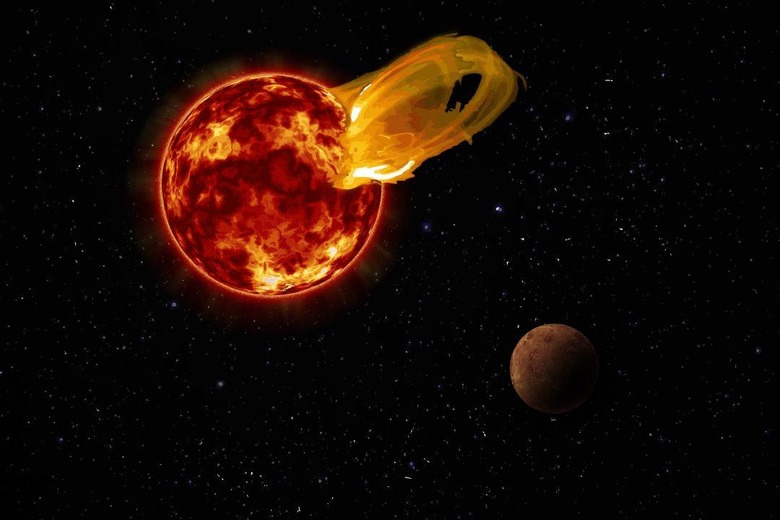

Bad news if you were thinking of relocating to Proxima Centauri b, the exoplanet closest to our solar system and once believed to be a decent candidate for supporting life. The planet, approximately 4.2 light years or 25 trillion miles from Earth, orbits the red dwarf Proxima Centauri, in a position where – in theory, at least – water could exist as a liquid on its surface. Unfortunately, Proxima Centauri isn't an especially welcoming star.

In fact, it was responsible for a massive stellar flare in March 2017, researchers now believe. The gush of high-energy radiation not only increased Proxima Centauri's brightness by 1,000 times for a period of around ten seconds, but washed across Proxima b. Although brief, it would've seen the exoplanet get 4,000 times more radiation than the Earth gets from our own Sun's flares.

Unsurprisingly, that has damning implications for whether life could survive there. In fact according to the team, led by Carnegie Science's Meredith MacGregor and Alycia Weinberger, it's enough to question whether the exoplanet could be habitable in future – or, indeed, was every amenable to life at all.

"Over the billions of years since Proxima b formed," MacGregor explains, "flares like this one could have evaporated any atmosphere or ocean and sterilized the surface, suggesting that habitability may involve more than just being the right distance from the host star to have liquid water." Proxima Centauri was known to undergo much smaller x-ray flares, caused by magnetic activity created by convection through the stellar body. However, those flares were believed to be along the lines of the x-ray emissions from our own Sun.

The incident took place on March 24, 2017, and was spotted in results from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, or ALMA. That's made up of 66 radio telescopes, either 39 feet or 23 feet in diameter, located in the Atacama Desert in Santiago, Chile. Scientists are using them to explore star births during the early days of the universe, in addition to figuring out what sort of planetary formation has taken place in star systems closer to our own.

ALMA had been observing Proxima Centauri for ten hours between January and March in 2017. The large flare – which was preceded by a smaller one – lasted just a fraction of that time. Still, it's enough to cast doubt on other assumptions that had been made about the system as a whole.

For instance, an earlier interpretation of the ALMA data had concluded that the shifting brightness of the star were down to multiple dust disks that encircled it. That, it was suggested, indicated more planets or similar in the same stellar system. With this new flare explanation, however, the possibility of significant dust may simply not be the case.

"There is now no reason to think that there is a substantial amount of dust around Proxima Cen," Carnegie's Weinberger points out. "Nor is there any information yet that indicates the star has a rich planetary system like ours."

IMAGE Roberto Molar Candanosa / Carnegie Institution for Science, NASA/SDO, NASA/JPL