NASA's Plucky Cassini Is About To Buzz Saturn's Epic Rings

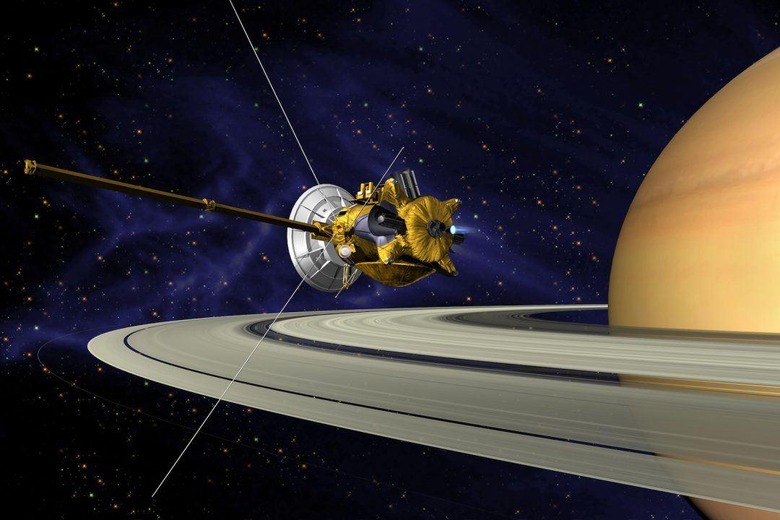

It's been a whirlwind adventure for NASA's Cassini spacecraft, beaming back incredible photos from Saturn over the past years, but its most exciting mission is almost upon us. The research probe has been surveying Saturn from different angles since 2004, along the way capturing shots of its moons and more, but now it's the turn of the planet's most notorious feature to get some attention. Cassini is about to buzz Saturn's rings.

Thanks to some careful adjustments to Cassini's orbital pattern, the spacecraft is about to start diving like a dolphin through the edges of the rings. Starting this Wednesday, November 30th, and expected to run until April 22, 2017, twenty dives will take place, one every week. It'll send the craft through hitherto-unexplored parts of one of our solar system's most distinctive features.

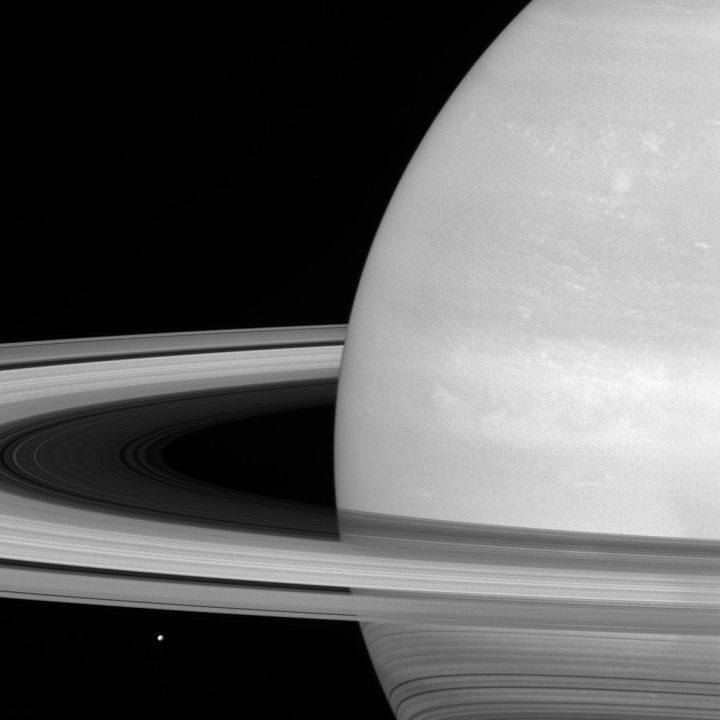

Though from a distance Saturn's rings look almost solid, in fact they're comprised of many millions of individual particles. The vast majority is ice, ranging in size from mere micrometers up to to several meters in diameter, with a little rock thrown in too. As recent shots from Cassini show, like the image below, they dwarf Saturn's moons – in this case, Mimas just underneath the rings in the lower left corner – though their overall mass is far less.

What we haven't been sure of so far is exactly where they came from. That's one of the questions scientists – including those at the Jet Propulsion Lab at NASA, which is running the Cassini mission – hope to address now. Initially, the spacecraft will run straight through two of the more minor rings, each produced after meteors hit two of Saturn's smaller moons, Janus and Epimetheus. However, by March or so, Cassini should be running through the edges of the so-called F ring.

It's the name given to the outer boundary of the main ring system, a roughly 500 mile wide band that circles the planet. Again, though it may look it, the F ring isn't stable, its composition and form constantly changing. Cassini will use onboard instrumentation designed to sample both particles and gases as it dives.

"We're calling this phase of the mission Cassini's Ring-Grazing Orbits," Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California said of the project, "because we'll be skimming past the outer edge of the rings." Nonetheless, NASA has been cautious with the flight plan to make sure the spacecraft is in minimal danger. While it may graze the F ring, it'll still be almost 5,000 miles away from it, where dust is not believed to present a significant hazard.

Cassini will first begin by snapping high-resolution photos of the composition of the rings, at roughly 0.6 miles per pixel. That's expected to confirm the existence of theorized "moonlets" that affect the topography of the rings but are yet to be visually confirmed. Come March, it'll be positioned perfectly to hopefully shoot images of dust eruptions backlit by the sun.

Still, while it may be the most exciting challenge of the Cassini mission to-date, it won't be the most dramatic. From April 2017 the spacecraft's days will be numbered, its dwindling fuel levels just sufficient to send it into a final, tight orbit of Saturn and then on a last dive through into the planet's atmosphere.