Microsoft Project Saving Data In Glass Could Safely Archive It For Millennia

Glass might not be the first material you think of when it comes to long-term resilience, but Microsoft's new Project Silica could turn it into the storage method of choice for saving data you really don't want to degrade. Brainchild of the company's Microsoft Research team, Project Silica encodes information on a super-strong slice of glass – and to prove it works, they stored a classic movie on there.

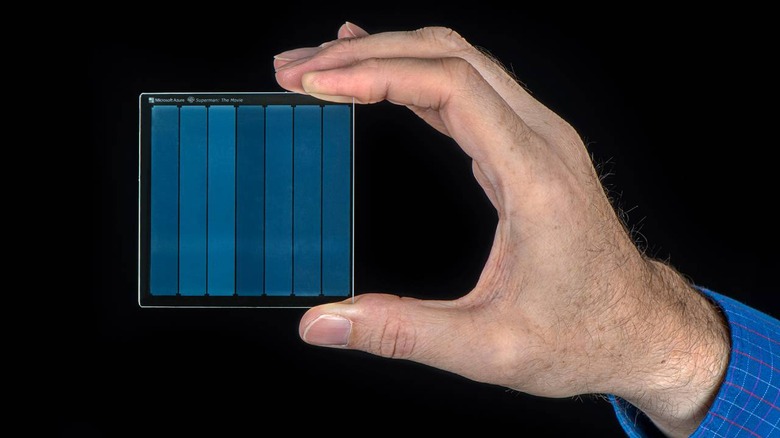

Teaming up with Warner Bros., the two companies stored – and, importantly, successfully retrieved – a copy of "Superman" on glass. The 1978 film was saved on a 75 x 75 x 2 mm piece of silica glass.

You might not think there was much chance of losing

"Superman" any time soon, but archival storage is a big concern as the amount of data in the world grows. Existing systems, whether they rely on magnetic tape, solid-state drives, or enterprise-class hard-drives, may be long-lasting, but they still can't guarantee data safety over extended periods. When it comes to surviving natural disasters, and doing so without being sealed up in a MIL-SPEC vault, something new was required.

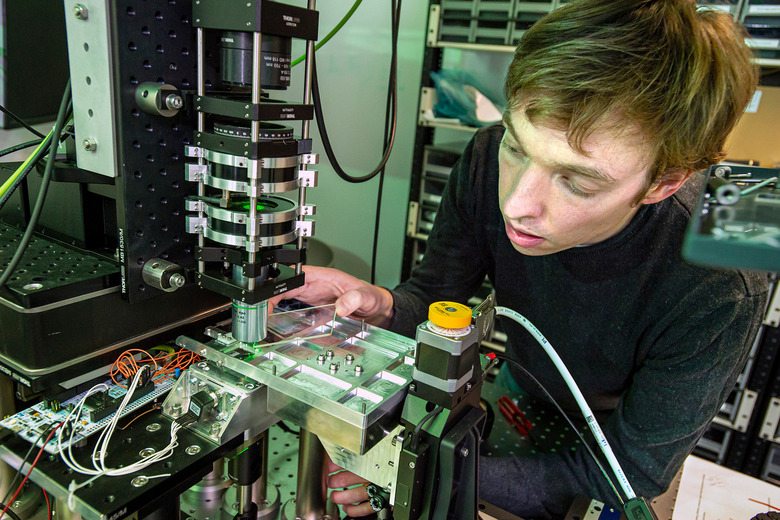

Project Silica taps into advanced ultrafast laser optics to do just that. The laser creates layers of three-dimensional nanoscale gratings and deformations, at various depths and angles, in a piece of hard silica glass. It's a little like the groves and bumps on an old vinyl record, but at a far more condensed and complex scale.

The "needle" in this case are machine learning algorithms, which decode images and patterns created by shining polarized light through the glass. A 2mm thick piece of glass, like the one used in this demonstration, can contain more than 100 layers of data. Each layer consists of physical deformation of the glass as individual "voxels," and then the machine learning algorithms jump between them to decode them.

Turns out, glass is actually perfectly suited to this. Quartz glass is unexpectedly resilient, able to withstand 500+ degree temperatures, being boiled or microwaved, or even being scoured with steel wool. Since the data is stored inside the glass, not on its surface, it made no difference to how readily the data could be read back.

It's early days for the technology, still. Right now, though the machine learning algorithms can access data non-sequentially from the glass storage, that process still needs to be faster. Actually encoding the data in the first place needs to be quicker, too, Microsoft says, and work is underway on improving the density at which the data is stored.

All the same, it's promising stuff, and Warner Bros. is apparently eager to continue development. The studio currently has a complex multi-step process by which key releases are archived as analog film, but it's too expensive to do for every piece of media. If Project Silica could be made cheaper and more straightforward than that, it could result in a new way of saving data that doesn't need specialist storage but could be relied upon to last thousands of years.