Herschel Space Telescope Watches Our Neighborhood Black Hole Feasting

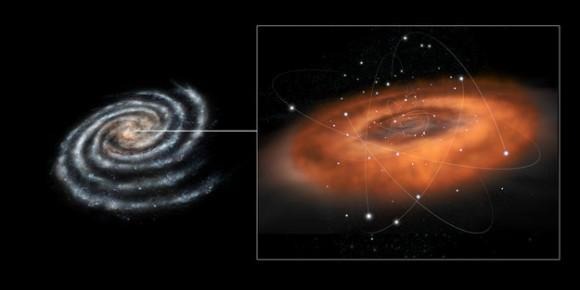

Never before seen observations of the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way have been made by the Herschel space observatory, revealing unexpectedly huge temperatures as the stellar body chews through gas and dust. Sagittarius A*, the black hole around 26,000 light years from our solar system, had previously been shrouded in too much space debris to clearly make out the processes going on around it; however, thanks to new work by the European Space Agency, new theories around radiation have been spawned to explain the 1,000-degree centigrade heat.

Before these latest observations, astronomers had assumed the interstellar clouds around Sagittarius A* would be much in line with regular clouds, with temperatures dawdling just about absolute zero (-273-degrees C). In actual fact, the black hole is surrounded by incredibly hot molecular gases, in the most central region at least, with only theories to explain why that might be the case.

Contributing to the heat – but unlikely to be responsible for all of it – is the cluster of massive stars around the black hole, the ESA says. Their output of ultraviolet radiation undoubtedly causes some of the unusual temperatures, but is not enough alone.

One theory, Doctor Javier Goicoechea of the Centro de Astrobiología, Spain, suggests, is that "emission from strong shocks in highly-magnetised gas" that also surround Sagittarius A* could be partially responsible. That could be the result of gas cloud collisions, or from the streams of hot gas that are being pulled toward the supermassive black hole.

Sagittarius A* masses around four million times that of our own Sun, and is the closest active black hole to Earth. "Herschel has resolved the far-infrared emission within just 1 light-year of the black hole," Goicoechea explains of the new findings, "making it possible for the first time at these wavelengths to separate emission due to the central cavity from that of the surrounding dense molecular disc."

Although black holes have been observed for many years, it's only with recent advances in equipment that more accurate measurements could be taken. Sometimes those observations come unexpectedly; one black hole suddenly woke and consumed huge quantities of matter from a nearby planet while they had been taking measurements nearby, for instance. Earlier this year, meanwhile, scientists managed to measure a black hole's spin for the first time.