Google Pacifies Euro Privacy Advocates With Google.com Fudge

Google's controversial "Right to be Forgotten" system will be expanded to the US version of the search engine, following a lengthy battle with privacy regulators. The tool launched back in May 2014, a way for European users to request personal details be removed from Google's index on the grounds that they were outdated or incorrect.

Its launch followed a ruling by the Court of Justice of the European Union which stated that search engines had an obligation to prune personal mentions should they be "inadequate, irrelevant or no longer relevant, or excessive in relation to the purposes for which they were processed."

In response, Google set up an on-request system by which those contesting items in its index could make their case for removal. It proved popular, too, with 12,000 requests made in a single day, and Google committing to manually reviewing each.

However, much to the chagrin of some European regulators and watchdogs, Google also refused to apply the index changes across every localized version of its search engine.

So, while a European user might no longer show up in search results on the UK, French, or German versions of Google, if they looked for the same term on Google.com, the original – and contentious – results could still be found.

That loophole in how Google interpreted the Court's ruling has led to fierce debate between the company and privacy regulators such as France's CNIL, or the Commission nationale de l'informatique et des libertés. Google's argument is that it is not in the business of censorship and that free speech laws in the US go counter to what is being asked of it; the retort has been that it has only partially complied with what is legally required of it.

CNIL threatened a €150,000 ($169k) fine for non-compliance.

Now, Google is taking further steps to address those perceived shortcomings. The company still refuses to edit its non-European indexes; however, it will use the location of the person making the search to decide whether information subject to a granted "right to be forgotten" request should be visible.

The change will also rely on the specific country where the original request was made.

So, if a person in France uses Google.com, the US version of the site, to search rather than Google.fr, the French version, they'll still see the pared-back results as long as the "right to be forgotten" request was made in France. Google will rely on IP addresses to identify where each person is searching from.

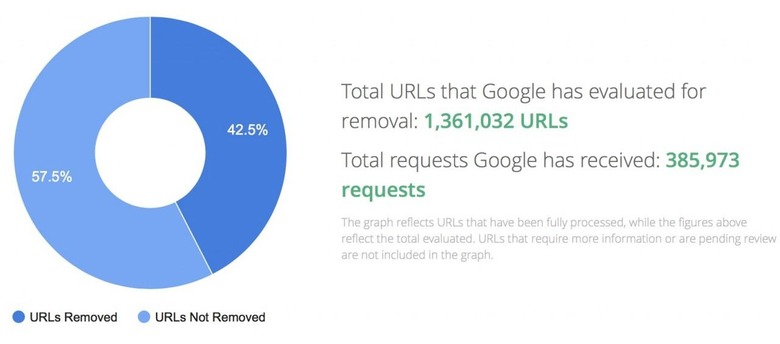

It's an unusual way of further implementing the ruling, and it remains to be seen how CNIL and others publicly respond to it. So far, Google says it has delisted around 42.5-percent of the URLs it has been asked to remove, with Facebook results the single most impacted site.