Forget Vantablack, This Ultra-White Paint Is The Brightest Ever

The whitest paint ever created is being shown off with glaring results, and could one day help significantly reduce cooling costs for cities in extreme climates. The ultra-white paint is the handiwork of a team of engineers at Purdue University, and reflects a huge 98.1-percent of sunlight – enough, in some conditions, to actually cool surfaces below ambient conditions.

Typically, "heat rejecting" paints that are billed as helping reduce the degree of air conditioning buildings require in order to remain comfortable inside don't actually cool the building. Rather, they focus on preventing them from heating up passively, by reflecting large amounts of the energy from the sun.

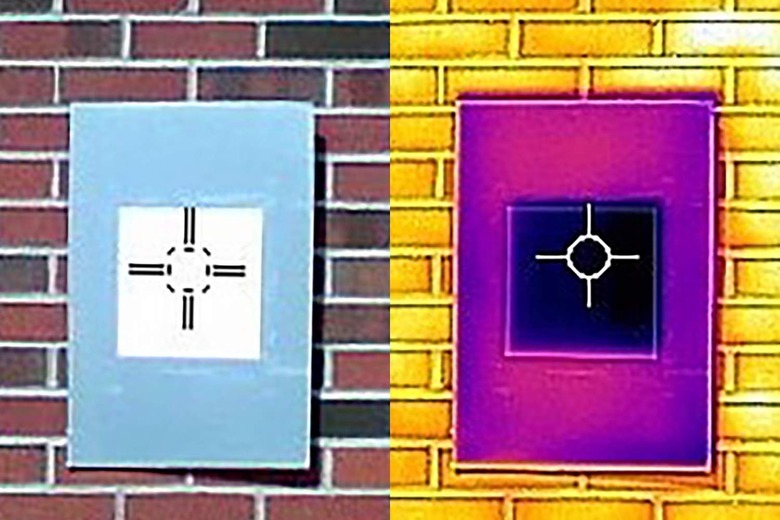

This Purdue paint, however, goes further than that. In tests with infrared cameras and boards treated with the ultra-white paint, they showed that the sections it covered were actually lower in temperature than the surrounding conditions. That's because it not only reflects visible light, but infrared heat too.

The team behind it is no stranger to making exceptionally white paint. In fact, they made headlines last year with a previous iteration, which at the time could reflect 95.5-percent of sunlight.

We're not talking a small degree of cooling, either. Obviously the paint would have to be applied to a considerable area of the building, but if that could be done then the potential upside to power use is considerable.

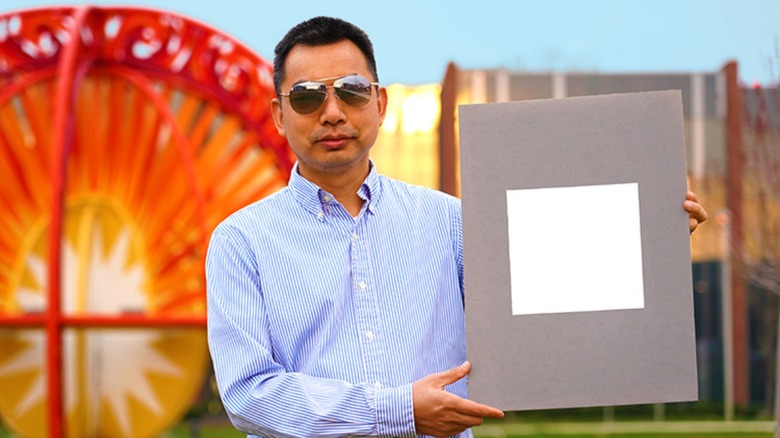

"If you were to use this paint to cover a roof area of about 1,000 square feet, we estimate that you could get a cooling power of 10 kilowatts," Xiulin Ruan, a Purdue professor of mechanical engineering, explains. "That's more powerful than the central air conditioners used by most houses."

It's not the first attempt to go to extremes with paint, of course, though arguably its finishes at the opposite end of the scale which are more notorious. Vantablack, for example, is one of the darkest materials known, capable of absorbing up to 99.965-percent of visible light. However it's not so much a paint as a chemical vapor deposition process, where tiny vertical tubes – that each capture light rather than reflecting it – are effectively "grown" on a substrate.

This ultra-white paint is different, however. Two factors combine to produce the finish, firstly the high concentration of barium sulfate, which was found to be highly reflective. The individual particle of barium sulfate, meanwhile, are different sizes. "How much each particle scatters light depends on its size," the researchers explain, "so a wider range of particle sizes allows the paint to scatter more of the light spectrum from the sun."

While there are obviously potential benefits here for buildings in hot conditions, the paint also works even in low temperature environments. At night, for example, the surfaces treated were up to 19-degrees Fahrenheit cooler than their ambient surroundings. In an outdoor test with wintery conditions of 43 degrees Fahrenheit, the paint lowered the treated surface by 18 degrees Fahrenheit compared to the ambient.

Importantly, the technique used to create the paint is compatible with existing commercial paint production, the Purdue team says. It "can potentially handle outdoor conditions" like commercial paint too, they claim. Attempts to make it even more white will take its toll on that factor, however, since more particle concentration leads to greater breaking and peeling.

A paper on the formulation has been published today, and the paint is currently going through the patent process ahead of possible commercialization.