Despite Facebook Drone Crash, It's All "Successful" Testing

Does your vast, internet-broadcasting solar-powered drone need to land in one piece in order to be considered a success? Facebook clearly doesn't believe so, giving the Aquila internet drone test flight back in June a rave review, despite a freshly-confirmed safety investigation being carried out by US regulators. Their complaint: the drone flight, despite what Facebook might have led us to believe, wasn't quite such a perfect performance.

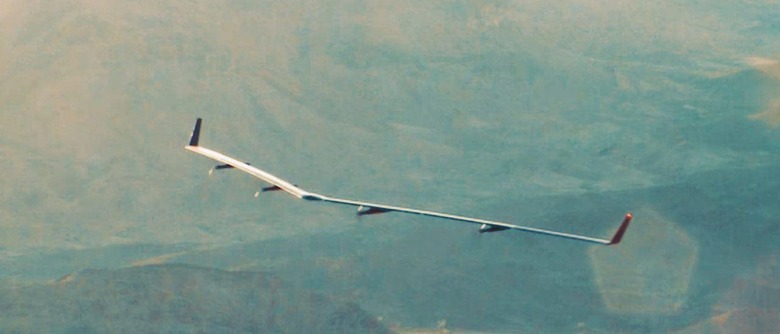

The test took place back on June 28, with Facebook taking the solar-powered aircraft to Yuma, Arizona. It was to be the first trial of the full-sized version of the drone, Facebook's engineers having flown one-fifth scale models in earlier tests. Aquila is designed for extended periods of flight time, using solar power to stay airborne; the goal, the team at the social network suggests, is to climb to between 60,000 and 90,000 feet and stay there for up to 90 days at a time.

By the end of the day, the flight was being as "so successful" that Facebook opted to keep the drone active for three times longer than originally intended. Although its 90 minute active time was a fraction of the roughly three months the final design is aiming for, the low-altitude test was enough to bring Facebook chief exec Mark Zuckerberg out to celebrate. Now, though, questions are being asked about just how safe the design actually is.

A new report by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) has revealed that, while Facebook's recount of the June test was glowing, a throwaway comment about a structural failure Aquila experienced was more serious than initially believed. Indeed, an NTSB spokesperson said that the drone landed with "substantial" damage. According to the agency's own definition, that could mean a hefty repair bill, among other issues.

"Substantial damage means damage or failure which adversely affects the structural strength, performance, or flight characteristics of the aircraft," the NTSB says. "This type of damage would normally require major repair or replacement of the affected component." Bent fairings, dents or punctures in an aircraft's skin, or damage to landing gear, tires, flaps, brakes, or wingtips would not be considered "substantial" damage the NTSB adds.

Even if nobody was injured, the NTSB's rules require an accident report be filed immediately after substantial damage be recorded. That report, and subsequent findings by the NTSB, are yet to be released. A spokesperson from the agency confirmed the fact to Bloomberg this week.

From Facebook's perspective, however, while this particular fault was not highlighted, it was never going to be a deal-breaker for Aquila. Indeed, the company says that the whole point of the testing is to push the drone not only to the limit but past the point where failures are predicted. After all, without that experience it'll be difficult to know how future flights could go wrong and where redesigns might be required.

"This test flight was designed to verify our operational models and overall aircraft design," Jay Parikh, Global Head of Engineering and Infrastructure at Facebook, wrote in the aftermath of the trial. "To prove out the full capacity of the design, we will push Aquila to the limits in a lengthy series of tests in the coming months and years. Failures are expected and sometimes even planned; we learn more when we push the plane to the brink."

All the same, the mention of Aquila's structural issue was buried in a second, more technical post by project members Martin Luis Gomez and Andrew Cox; in that post-mortem, the incident was described only vaguely. "We are still analyzing the results of the extended test, including a structural failure we experienced just before landing," Gomez and Cox wrote. "We hope to share more details on this and other structural tests in the future."

Undoubtedly, it was too much to expect a first flight of this sort to go perfectly, and as Facebook says the whole point of trials is to shake out any potential problems sooner rather than later. What has prompted concern, though, is the apparent absence of transparency in the post-test report. That apparently attempted to minimize what, going by the NTSB classification at least, would appear to be a more serious issue than the Aquila team let on.

Without any further detail from either Facebook or the National Transportation Safety Board as to whether the agency's investigation is more routine or otherwise, it's hard to know exactly what challenges the Aquila project faces moving forward. The predominantly carbon-fiber craft has a number of hurdles to overcome, not least being sturdy enough to survive harsh weather conditions at the altitudes at which it's intended to fly, but also light enough to minimize power requirements. Facebook says, for instance, that the drone is designed to use the equivalent energy of a microwave while at 60k feet.

Even so, around half of the overall mass of the craft is made up of batteries. These are recharged during the day from solar panels on the upper-sides of the wings, and then used to power flight during nighttime. Given winter conditions, that could mean sufficient electricity for anything up to 14 hours at a stretch.

The possible benefits, though, are significant. Facebook plans to use laser communication between drones like Aquila and ground-based stations, with a new type of luminescent detector developed that allows transmission between the huge distances. With a flock of such aircraft in play, comparatively expensive installations of wired or wireless internet systems could be avoided altogether.