DARPA Wants To Piggy-Back Satellites On Jets To Space

Getting payloads from Earth and into space is shaping up to be big business, and now DARPA is weighing in with its own piggy-back proposal that could see jets help take satellites into orbit. Dubbed the Airborne Launch Assist Space Access (ALASA) program, the scheme isn't designed to challenge SpaceX and Boeing for their Launch America contracts, taxiing NASA astronauts to the International Space Station, but instead to act as a more affordable route to put up things like communication and weather satellites with relatively short notice. The goal is a roughly $1m delivery charge and, maybe more importantly, a far faster turnaround than existing methods.

Currently, there are a limited number of locations in the US which can handle a satellite launch, and so the waiting list for getting payloads of 100 pounds or less is measured in years. That means replacing broken Department of Defense or other government satellites that may have malfunctioned or broken can't be done on a whim, potentially leaving gaps in coverage.

ALASA's strategy is to tackle cost-cutting and scheduling delays on a number of fronts, most obviously by taking advantage of commercial aircraft to go part of the way. A regular jet would carry the special DARPA launch vehicle on a belly-mounted harness, taking it to high altitude where it would be released.

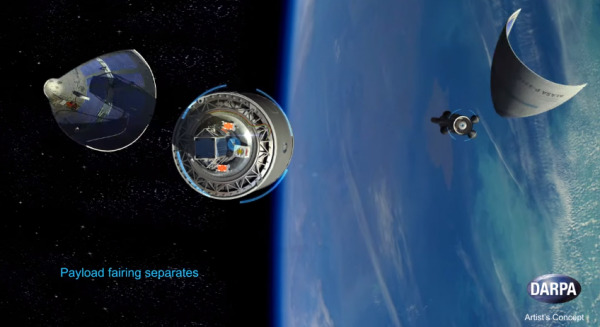

The launch vehicle would then travel to the intended location under its own steam, finishing off by deploying the final payload. Although it would not be recoverable, the conventional jet obviously would be; more importantly, it could take off from any number of airfields, rather than demanding a specialist site.

Meanwhile, other phases of the proposal include developing standardized software that could be used to streamline the various processes involved in getting a sub-100-pound payload into space, as well as automatically monitoring flight conditions and auto-terminating them if an issue was observed.

Methods to use existing satellites for telemetry, rather than complex ground-based systems, would also mitigate another limiting factor for picking launch sites, while DARPA has ambitious plans to use a new high-energy monopropellant that combines both oxidizer and fuel into a single liquid, cutting the need for two distinct tanks in the process.

DARPA is hoping to run its first demonstration flight test later this year, followed by an orbital launch test in the first half of 2016. Assuming they go to plan, a further eleven demo launches are tentatively scheduled through summer 2016.

SOURCE DARPA