Broadcom Location Chip Promises Longer Wearables And True-AR

Location-based services and contextual augmented-reality on your smartglasses is fun, but not if they drain power so fast you only get a couple of hours of use from them. Broadcom believes it has the answer with its new BCM4771 GNSS SoC, a super-low-power chip to add location and health tracking to wearables while cutting battery consumption by 75-percent compared to existing positioning chips. It's a system that not only should make fitness trackers and smartwatches run for longer, but open the door to true augmented-reality headsets.

The BCM4771 is the first Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) targeted at low-power wearables, Broadcom claims, though that doesn't mean it sacrifices sensors. Built on 40nm processes, it has an integrated sensor hub to go along with the GPS chip, that cuts down on external probes required.

However, in addition to reducing bulk and promising a cheaper overall device, that sensor hub also lets Broadcom do some power-saving tricks with context. Since the chip is aware of speed and distance traveled, as well as being able to calculate metrics like steps-taken, it can selectively shut down non-relevant sensors – like ignoring steps when it knows the device is most likely in a car – to trim power demands.

Alternatively, if the motion-sensors spot that the chip is stationary, the GPS ping can be put into standby mode to also save power.

That will mean more efficient smartwatches and smart glasses, Broadcom suggests, while at the same time giving more accurate positioning and tracking data than existing systems.

The chip is most likely to show up in watches and fitness bands first, but the promise of greater precision in positioning will be all the more important when full augmented-reality glasses – such as the displays in Epson's Moverio – become more common.

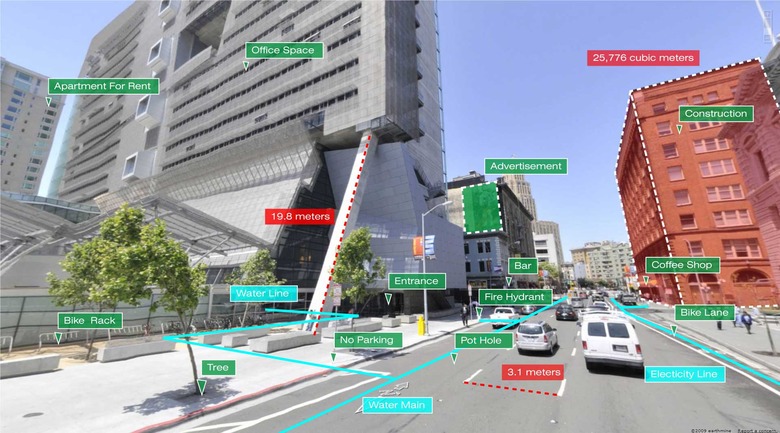

Then, if developers are to successfully overlay digital graphics over a real-world perspective, without causing headaches and user-frustration from misalignment in the process, the devices themselves will need a particularly accurate location fix. It's one of the reasons that true augmented- or mediated-reality is so difficult to do, and why so many of the early wearables – such as Google's Glass – opt instead to sit alongside the wearer's vision, not integrate with it.