Audacious Climate Change Plan Appeals To Wallets More Than Ethics

Increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to improve climate change seems paradoxical, but Stanford researchers argue that new tech and the promise of bottom line profits could coax big industry into getting greener. A new study proposes a more pragmatic approach to greenhouse gases, along with a financial lure to maximize compliance.

Carbon dioxide isn't exactly something that we've been encouraged to release. However, much more dangerous in terms of driving climate change is methane. That's a far more potent greenhouse gas.

What the Stanford-led project suggests, therefore, is a trade-off. Convert methane into carbon dioxide, it's theorized, and while the latter would increase, the overall net impact would be a benefit to the climate. It would also mean that processes which create methane emissions, like cultivating cattle or rice fields, could continue, because those emissions could be offset elsewhere.

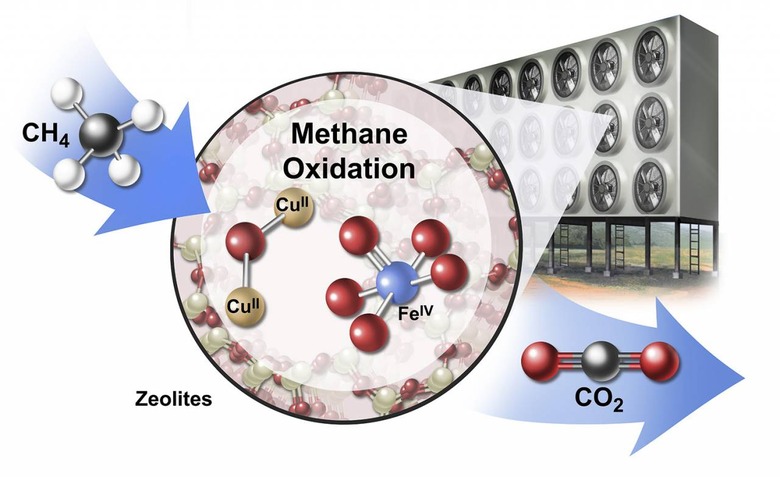

The technique relies on zeolite, a crystalline material made up primarily of aluminum, silicon, and oxygen. It could be applied like a methane-soaking sponge, the Stanford team suggests. They've even come up with a way to make it financially viable.

One possibility is a huge, fan-driven assembly, which would force air through a series of "tumbling chambers or reactors" within which there'd be powdered or pelletized zeolites along with other catalysts. Methane would be trapped by them, and then heated to release carbon dioxide.

Carbon offsetting could be implemented to encourage adoption, the researchers suggest. With predictions suggesting such offsets could be worth in excess of $500 per ton later in the century, a ton of methane removed from the atmosphere could work out to being worth more than $12,000. That way, a zeolite array sized like a football field could be worth millions of dollars each year in income.

Approximately 60-percent of methane is generated by humans, and it's currently in atmospheric concentrations roughly 2.5x greater than it was in pre-industrial levels. While still outweighed in volume by carbon dioxide, atmospheric methane lands a heavier punch in terms of climate change. According to the study, methane has 84 times the potency for climate system warming in the first 20 years post-release, versus carbon dioxide.

Turning back the clock on carbon dioxide was always going to be a challenge. Indeed, even if plans to remove hundreds of billions of tons of CO2 were successful, it would still leave the atmosphere with higher levels than in pre-industrial times. "In contrast," Rob Jordan, of the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, writes, "methane concentrations could be restored to pre-industrial levels by removing about 3.2 billion tons of the gas from the atmosphere and converting it into an amount of carbon dioxide equivalent to a few months of global industrial emissions."

Encouraging industries to adopt green technologies and policies has been an uphill struggle. Whether such players could be encouraged to be more green by adding a significant financial incentive remains to be seen.