Antarctic Fractures Could See Precarious Ice Shelves Crumble - With Dire Results

Huge fractures in the Antarctic ice shelves could see more than half of the precarious structures shear away, new research has warned, the latest potential consequence of untempered climate change. While melting Arctic and Antarctic ice have long been a known issue with rising temperatures, the possibility of even more dramatic changes in the glaciers adds a new element of urgency to tackling global warming.

Currently, researchers believe, glaciers are melting at increasingly rapid rates. One area in the East Antarctic, for example, is believed to have lost 268 billion tons of ice between 1979 and 2017, the glacier retreating nearly three miles in the process.

It's the stability of ice shelves that ring Antarctica, however, that caught the attention of a team of researchers at the Earth Institute at Columbia University. They focused on fractures that already pepper the shelves, and the possibility of liquid meltwater filling the gaps. Known as hydrofracturing, it's when heavier liquid water forces the fractures to suddenly split open.

The shelves themselves obviously constitute no small degree of water as ice. However they also serve as a vital barrier, slowing inland glaciers as they progress toward the ocean. One fear is that, should the ice shelves collapse, that greater sliding would be accelerated.

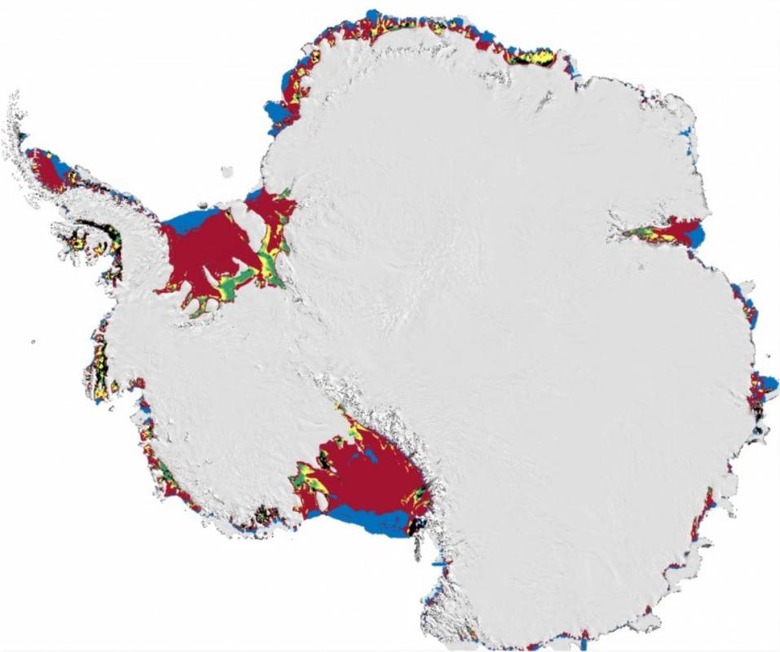

Anywhere between 50- and 70-percent of the areas of the ice shelves where they buttress against glaciers could be vulnerable to hydrofracturing, the team report in a study published this week in Nature.

"It's not just about melting, but where it's melting," Ching-Yao Lai, lead author and a postdoctoral researcher at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, explains. Ice shelves normally can be relied upon to hold up to massive forces, but hydrofracturing can undermine that, and rapidly.

A new modeling tool to estimate which areas would be most at risk was developed, taking into account not only the compression from the sides, but the way the ice stretches from back to front. Areas closer to land are less susceptible, because there the stretching force is not as strong. Conversely, the end portions of the ice shelves are more vulnerable, but typically aren't instrumental in holding back inland glaciers.

Still uncertain is just what sort of timescale could be involved. With so many factors to consider – including how much temperatures continue to rise, and how fast melt water might form and infiltrate the cracks – it's tough to say if this is an issue that could be significant over a matter of years, or more swiftly reach a tipping point.