Alzheimer's Treatment Restores Memory Function : Human Trials On Roadmap

Human trials are now in the conversation with recently famed "repeated scanning ultrasound" (SUS) Alzheimer's disease treatment research. Alzheimer's research saw a jolt of interest over the past year as scanning ultrasounds were found to be effective at memory restoration. In repeated scanning ultrasound treatments of mice brains, positive results of amyloid-β and memory restoration were enough to publish research in AAAS-certified Science Translational Medicine – a publication of good repute.

Back when the research was published, it included an abstract which described how Alzheimer's disease was treated in trials with mice. This was a nonpharmacological approach, said the paper, and it was effective in "restoring memory function in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease" in which amyloid-β is deposited in the brain." With repeated scanning ultrasound treatments, the mouse did not need any additional therapeutic agent "such as anti-amyloid-β antibody."

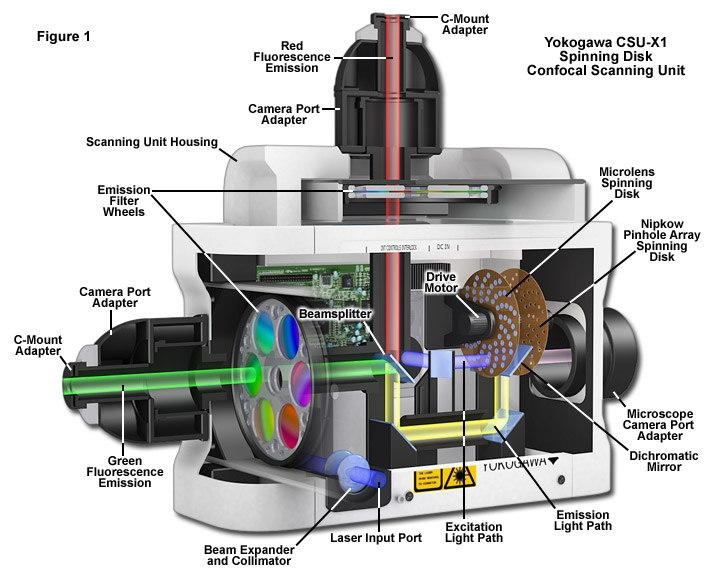

Researchers used Spinning Disk Confocal Microscopy as one of two ways of testing results. This sort of microscopy is a living-cell imaging technique, one that provides extremely precise results in living subjects, far greater than anything available in the past. While first introduced in the 1970's, it's only recently that microscope optical design and camera technology have made this sort of microscopy viable for this specific sort of test.

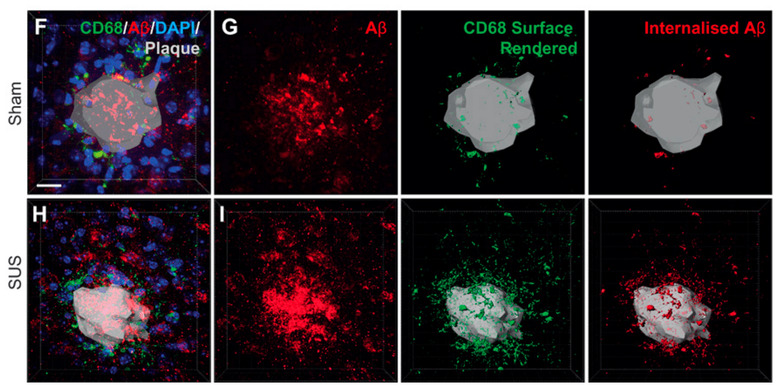

Using microscopy described above and 3D-reconstruction were used to find "extensive internalization of Aβ into the lysosomes of activated microglia in mouse brains subjected to SUS, with no concomitant increase observed in the number of microglia." When compared to control mice (sham-treated mice), repeated scanning ultrasound-treated mice were found to have reduced plaque burden. Entirely cleared plaques "were observed in 75% of all SUS-treated mice."

IMAGE ABOVE: ZEISS on Spinning Disk Confocal Microscopy. This is the Yokogawa CSU-X1 – not necessarily the exact model used by the researchers in this Alzheimer's project, but close enough for this example.

Two things are extremely important about this research. First – that it treats Alzheimer's at all. Of course the fact that this treatment actually does what it intends to is the first concern. Also of note is the fact that this treatment is effectively noninvasive.

More information can be found on the original research paper "Scanning ultrasound removes amyloid-β and restores memory in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model" in Science Translational Medicine 11 March, 2015: Volume 7, issue 278. DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa2512. Authors include Gerhard Leinenga and Jürgen Götz, and additional authors and affiliations can be found at the source.

ABOVE: Plaques imaged at high magnification in 3D. CD68 labeling revealed the extent of Aβ at the plaque site that was internalized by microglia into lysosomes. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used to visualize nuclei.

Where are we now?

Since the paper was published, the lead authors have appeared on news programs and commented on newspaper and magazine articles of all sorts. "This discovery resulted in significant media attention and public interest," said Professor Juergen Goetz, director of Clem Jones Centre for Ageing Dementia Research. "Importantly, the novel approach has not only been extended to rodent models having a tau tangle pathology, but resulted in a pilot study in sheep, which will address the problem of ultrasound attenuation that is associated with the thicker skulls of humans in comparison to mice."

Goetz works with The University of Queensland in Australia where CJCADR is housed within the Queensland Brain Institute. The other one of two main authors on the paper, Gerhard Leinenga, also spoke up recently on the events that've taken place since the release of their research paper.

"I had no idea how much interest there would be in the work—ongoing interest; two months after the announcement we're getting requests to do appearances on American television," said Leinenga. "The project is starting to open up a lot of physics and engineering questions as well as it starts to move towards how it could work as a device for human use."

Human Trials

CJCADR ultrasound research remains an animal-based project for the moment, but does have a portal for human trials in the future. As the researchers at The University of Queensland have suggested, "It will unfortunately take a few years until the device will be available and clinical trials can be initiated." But that doesn't mean hopeful candidates can't continue to raise awareness for the project in the meantime.

At this time there is no clinical trial contact list of any sort, and no locations for clinical trials has been selected as of yet. The researchers behind this project have suggested that patients and their families "maintain contact with their general practitioner or treating specialist who will be first to be informed of clinical trials" at a time at which they're made available.

Users of all sorts can sign up for the research team's newsletter through their mailing list as well. For those doctors seeking out the newest medications that can potentially reduce some symptoms of Alzheimers, enquiries on current clinical trials with the newest in new medications can be sent to Liz Arnold, Discipline of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, The University of Queensland, K Floor, Mental Health Centre, RBWH Herston Qld 4029, Tel: + 61 7 3365 5147, or with elizabeth.arnold@uq.edu.au for email. Inside the United States, doctors will want to contact the National Institute on Aging at 1-800-438-4380 or through adear@nia.nih.gov for email.