After Two Astonishing Years, NASA's TESS Is Onto The Next Exoplanet Hunt

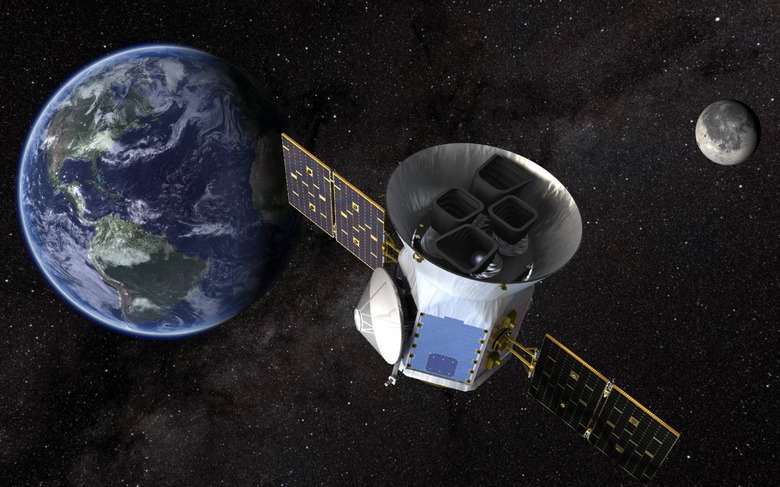

Just over two years after it first started hunting for new exoplanets, NASA's TESS has completed its primary mission – now, it's on to the next. The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite only began snapping images of the galaxy back in August 2018, and now NASA has a huge database of high-resolution imaging of distant stars.

It's not just fodder for screensavers, either. TESS' observations are looking for transits specifically, the slight dimming of a star's light as a planet in orbit around it passes in front from the satellite's viewpoint. With an array of wide-field cameras, TESS' data can then be used to figure out factors like mass, size, density, and orbit of those planets.

The primary mission saw TESS tasked with gathering images of around 75-percent of the sky. The first year focused on the southern sky, tracking 24-by-96 degree strips for approximately a month each. Then, it turned to the northern sky, and did the same thing.

Along the way it identified 66 new exoplanets, together with a further 2,100 possible exoplanets that are yet to be confirmed.

Next up comes the so-called extended mission. TESS will return to studying the southern sky, but with a much more rapid rate of capture. Whereas in its primary mission it took about 30 minutes for each capture, that'll be done in 10 minutes during the extended mission. Meanwhile the brightness of thousands of stars can now be measured every 20 seconds, NASA says.

It'll combine with the original method, which saw the brightness of tens of thousands of stars tracked every two minutes. As a result, TESS can better handle the changes in brightness that stellar oscillations can cause, not to mention get better detail on the flares from active stars.

If all goes to plan, the extended mission will run through until September 2022. It'll be about a year of southern sky observations, before spending 15 months on the northern regions and to survey areas along the ecliptic. That's of particular interest, as TESS has so far not taken images of the plane of Earth's orbit around our own Sun.

The goal is to use TESS data to hopefully identify a possible "Goldilocks" situation: an exoplanet similar to Earth, in an orbit at which position liquid water could exist on the surface, and thus which could have the basics for life to develop. We're still a long way from being able to visit such exoplanets, but TESS' data has already helped develop a shortlist of potential candidates.