How Long Term Space Travel Will Affect The Human Body

If we one day want to send astronauts to another planet, we're going to need to learn about what being in space for a long time does to the human body. Most of what we know about the effects of spending time in space comes from studying astronauts who visit the International Space Station (ISS). Astronauts typically go to the ISS for periods of six months, but some stay there for longer, like NASA astronaut Mark Vande Hei who recently spent 355 days in orbit. Looking at the effects on astronauts like Vande Hei can help researchers estimate what the effect of longer missions, like those lasting years, might be.

One of the most noticeable sources of change to the body in space is the lack of gravity. Without the force of gravity pushing down, fluids tend to pool in the upper parts of the body. That is what gives astronauts the famous "puffy face" look as fluids collect in the head. Some researchers think this movement of fluids is responsible for another common effect of spaceflight, which is reduced eyesight. Astronauts' eyeballs may be squished by this pooling fluid, making their eyesight worse.

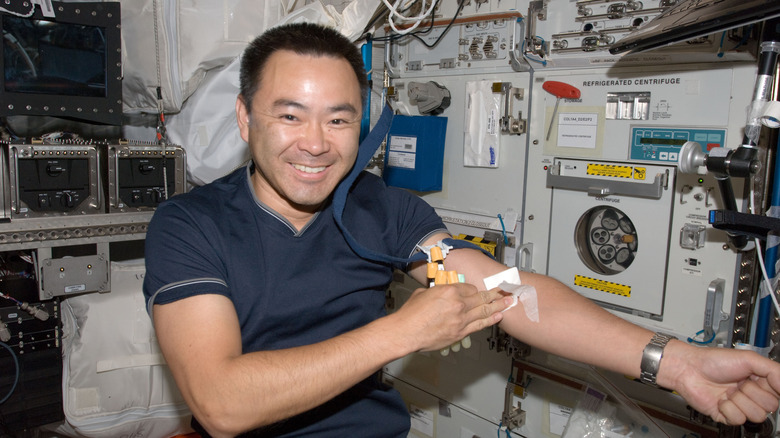

Another problem caused by lack of gravity is muscle loss. When bodies don't have to work against the force of gravity to stay upright, muscles are used much less and so waste away over time. That's why astronauts on the ISS spend so much time exercising. As you might expect, floating around without gravity gives some people motion sickness, as well. Called space sickness or, technically, space adaptation syndrome, this happens when people find it hard to adjust to microgravity and can experience nausea, vertigo, or headaches.

Comparing identical twin astronauts

One extremely useful way to understand the consequences of a particular action, like going to space, is performing a twin study. This is where two identical twins are selected and one is put into a condition –- in this case, spending a year in space –- while the other one lives their life as normal. Then, at the end of the test period, researchers can compare the two to see what differences have arisen. That's what NASA did with its landmark twin study, published in 2019, in which it compared the health outcomes of astronauts Mark and Scott Kelly after Scott spent a year in space on the International Space Station and Mark spent it on Earth.

The results, according to NASA, looked for changes in Scott's body at the physiological and molecular levels, as well as any cognitive changes. The researchers found changes to all sorts of aspects of the body, including changes to the protective telomeres that are part of our DNA and naturally shorten as we age. Scott's telomeres were changed by his time in space — but they actually got longer, which was surprising, and returned to normal length when he returned to Earth.

Other findings are that Scott's gene expression was slightly changed, and his gut bacteria was very changed too, though this could be due to eating the prepacked and dried food available on the space station. There was good news for astronaut health in this study, as well, showing that Scott's flu vaccines worked as expected and that his cognitive performance remained unchanged, meaning he didn't suffer from problems with alertness or spatial orientation.

Changes in genetics?

After NASA published its twin study, some of the results were reported inaccurately with misleading headlines suggesting that Mark's genes had been changed and that he was no longer an identical twin to his brother Scott. But that isn't right, as the Scotts remain identical twins. There were some changes to the way Scott's genes were expressed, but these were only small changes and were not related to his fundamental DNA changing.

"Mark and Scott Kelly are still identical twins; Scott's DNA did not fundamentally change," NASA wrote. "What researchers did observe are changes in gene expression, which is how your body reacts to your environment. This likely is within the range for humans under stress, such as mountain climbing or SCUBA diving."

NASA went on to say that the change to Scott's gene expression mostly went away after he had been back on Earth for six months, with only a 7% difference remaining after this time. That's a pretty small change. Even Scott Kelly himself tweeted a joke about the headlines regarding his DNA, joking that "This could be good news!" and that he wouldn't have to call Mark his identical twin brother anymore. So it's interesting that spaceflight seems to make some small long-term changes to gene expression, but there isn't evidence that going to space changes your DNA.

Effects over the long term

This is what we know about the effects of space flight that lasts for periods of months, or up to a year. But for longer missions, like those being considered to send humans to Mars, we'd need to look over periods of years. One piece of good news for would-be space travelers is that many of these effects are due specifically to a lack of gravity, which is experienced by those in orbit or traveling through space. A mission to another planet like Mars would see astronauts spend more time on the planet's surface. While Mars' gravity is weaker than Earth's, it is likely that the presence of at least some gravity would ameliorate some of these effects. And of course, if we could create a system of artificial gravity, then that would help as well.

But there are still effects of long-term spaceflight to consider, such as bone loss. For the same reasons that muscle is lost when on spaceflights, bones lose their mass over time, too. Researchers estimate that astronauts lose between 1% and 2% of their bone mineral density for each month spent in space, which means this could pose a serious problem for longer missions, as noted by the Canadian government. There is also the problem of radiation exposure, which happens to all astronauts who travel outside of the Earth's protective magnetosphere and that becomes a more severe threat to health the longer the astronaut is away. NASA and other agencies are continuing to research these issues using data from current astronauts as well as laboratory work and ground analog studies.

"On upcoming Artemis missions to lunar orbit and the surface of the Moon, even more data will be collected as this work continues," NASA writes. "On future longer duration missions to the moon and Mars, astronauts will benefit from years of research that will ensure they will be able not just to survive, but thrive on their spacefaring missions."