The Fascinating History And Evolution Of Photography

In modern times we take cameras for granted. Most of us carry them around in our pockets all the time and have the ability to take sharp, true-to-life photos and video any time we want and share those images with one another anywhere in the world. That wasn't always the case, though.

For thousands of years there was no reliable way to share images with another person. If you weren't there to see something for yourself, you just had to take someone else's word for it. For a long time, the best way to capture images of a person, object, or event and share it with someone else was through illustration. Those images, for better or worse, were only as good as the artist and their reference material. As a consequence, we ended up with some truly hilarious illustrations of exotic animals, drawn by people who had never seen them (per Bored Panda).

Cameras, as a technology, are still relatively in their infancy, having only existed in anything resembling their modern form for about two hundred years. Still, they've come an incredibly long way during that time, having transformed from little more than shadows to the incredibly detailed images we have today.

Camera Obscura

Long before there was even primitive photography, people understood that there was a relationship between light and images. It's possible that you've personally experienced the physical mechanics behind early image capturing devices. Light coming through a window or partially drawn blinds can project an image from outside onto a wall, (per MIT).

As explained by Photography History Facts, the first recorded mention of this effect was by Mozi, a Chinese philosopher in the 5th Century BC. About a hundred years later, Aristotle noted that a solar eclipse shining through the leaves of a tree projected an image of the eclipse on the ground.

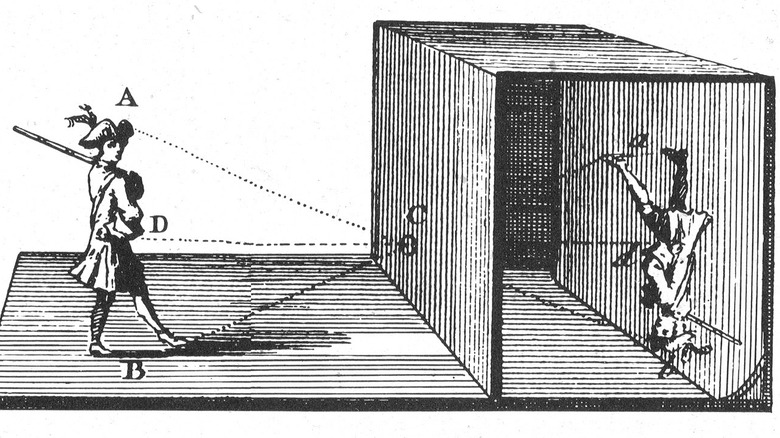

Later, the same effect was used intentionally by way of a device called a camera obscura, Latin for "dark chamber," (per Britannica). A camera obscura is essentially a box with a pinhole or a lens on the outside. Light travels through the pinhole and hits the opposite wall where the image is displayed. However, because rays of light travel in a straight line, the image is reversed and turned upside down.

Early users of the camera obscura would place a piece of drawing paper on the wall receiving the image so that it could be traced. This was one of the earliest ways images could be captured on paper, though indirectly, and was a direct predecessor to the camera.

Johann Heinrich Schulze's photograms

After the camera obscura, the next challenge in photography was finding a way to fix the images inside the box in a more permanent way. Scientists, engineers, and enthusiasts turned to chemistry for an answer.

By the 1970s it was known in scientific circles that certain chemicals changed color or darkened when exposed to light. As explained by the Science History Institute, Johann Heinrich Schulze, a German physicist and medical professor, used a combination of chalk and silver nitrate to temporarily capture rudimentary images. When exposed to sunlight, silver nitrate turns dark. Using that knowledge, Schulze filled a jar with his mixture and placed a stencil on the outside. Any part of the mixture covered by the stencil remained unchanged while the portions which were uncovered darkened.

This method couldn't create complex images with the level of detail needed for true photography, but Schulze did succeed in writing letters or shapes using sunlight. This proved that the combination of chemistry and light could fix images at least semi-permanently.

The oldest surviving photograph

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce spent much of his life experimenting with photographic processes. He was enamored with the idea of capturing the image displayed inside a camera obscura and experimented with many different chemical agents in his attempts to achieve a photograph.

In his first early experiments, he placed sheets of paper treated with silver salts inside a camera obscura. Like Schulz's photograms, they darkened where the light was present, creating a negative of the image outside. As explained by the Maison Nicéphore Niépce, he then got to work trying to create positive images using iron oxide and manganese black oxide, with some success. The major challenge was preventing the image from overexposing as soon as it was removed from the camera obscura. Images could be created but couldn't be fixed permanently.

Eventually, he moved away from treated photo paper and onto a polished pewter plate covered in bitumen of Judea, (per the Abby Newsletter). This combination worked but the exposure times were too long for capturing fleeting occurrences. To that end, Niépce set his camera sights on landscapes. He positioned his setup in the upper-story window of his house, looking out on the world, and left it there for eight hours. Washing away the remaining bitumen prevented any further exposure after being removed from the box and the image was fixed. Compared to today's standards it's a grainy and lifeless image, but given the context of the time, it's a masterpiece.

Daguerreotypes

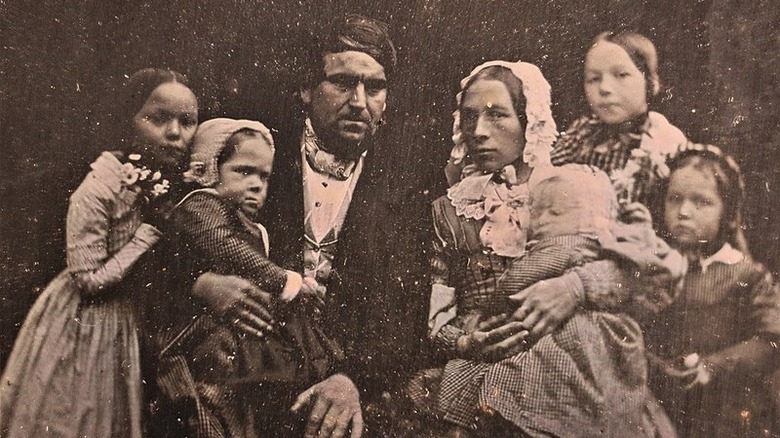

In 1839 Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre revealed his method for capturing images to the public. The overall philosophy of Daguerre's method was similar to that which Niépce used, but the result was significantly better.

In place of a polished plate, Daguerre used silver-plated copper polished until it gleamed like a mirror. As explained by the Library of Congress, the copper plate was then treated over iodine until it acquired a yellowish color. To avoid exposure, the plate was then transferred in a lightproof container to the camera. Developing the image involved exposure to hot mercury. Finally, salt and gold chloride permanently fixed the image to the plate.

The major advantage over Niépce's method, aside from the improved picture quality, was the significantly reduced exposure time. Even the earliest daguerreotypes only required an exposure of between three and fifteen minutes. Later improvements to the process further reduced exposure times to a minute. This allowed images to be made not just of still landscapes, but of people and just about anything else which could be convinced to hold still for sixty seconds.

Panoramic cameras

Those early photographs had a relatively narrow field of view, requiring photographers to select finite subjects like individuals or small groups, or else take their pictures from a considerable distance, but it wasn't long before that changed. Early panoramic photos were constructed by taking a series of daguerreotypes and placing them in sequence, (per the Library of Congress), but even when done successfully they rarely looked like a single image.

In 1859, Thomas Sutton, a photographer from Jersey invented what is considered to be the world's first wide angle lens, making early panoramic pictures possible, (per Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias).

The trick behind Sutton's novel camera was the design of both its body and the lens inside. As explained by Museums Victoria Collections, the wooden camera body had a curved back which held metal plates used to capture the exposures. The lens, positioned in front of the plate, was a hollow glass sphere which Sutton filled with distilled water.

The sphere captured light from a greater area and projected it onto the plate at the back. Metal plates were treated with sensitizing chemicals and exposed before the chemicals dried. The resulting images were a negative of their subject with a field of view between 120 and 140 degrees.

Color photography

Scottish mathematician James Clerk Maxwell is most well known for his contributions to the field of electromagnetism, but he also made an impact on the history of photography.

As explained by History of Information, Maxwell revealed his photograph, an image of a colored ribbon, during a lecture at the Royal Institution in 1861. Maxwell is credited as having devised the method for capturing color in a photo, but he didn't actually capture the image himself. That honor when to Thomas Sutton, who you may remember from the previous slide, as having invented wide angle photography.

The method for capturing colors in a still image involved taking three separate exposures, each utilizing a differently colored filter. Exposures were taken with red, green, and blue filters before being recombined into a final composite.

While the photo was successful at capturing some of the apparent colors, it isn't perfect, relating to limitations in the color sensitivity of the photographic plates. Even still, this unassuming image of a ribbon marks the beginning of additive color photography, a method which remained dominant for decades, (per Science and Media Museum).

Capturing motion

To this point, photography had succeeded in capturing brief moments in time. Despite the exposures sometimes taking several seconds, minutes, or even hours, the images obtained through these early methods appeared as discrete blips, captured in amber. The next step, of course, was to capture motion.

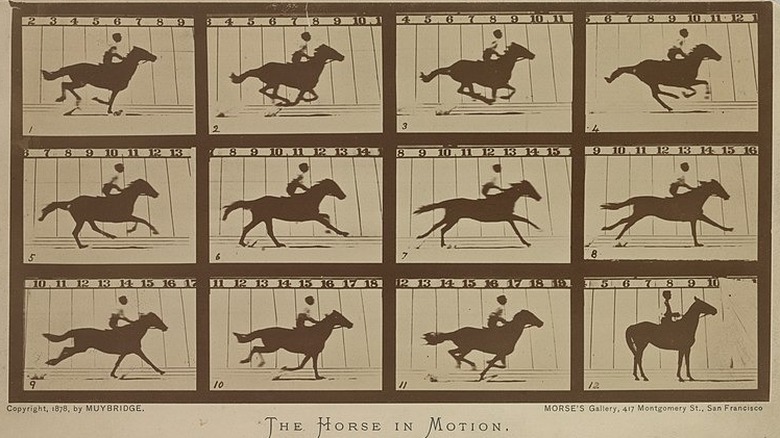

As explained by Smithsonian Magazine, the person perhaps most responsible for pushing the issue was Leland Stanford, the founder of Stanford University. Like Maxwell, Stanford didn't capture the resulting images himself, instead partnering with photographer Eadward Muybridge, and he did it to answer a nagging question. He wanted to know if all four of a horse's hooves left the ground at the same time when they run.

To pull it off, Muybridge devised a complex collection of twelve cameras, each of which were triggered by a tripwire. Stanford set his horse coursing down the racetrack, pulling a cart behind it. As the wheels of the cart rolled over each of the tripwires, an exposure was taken. In only a few seconds, Muybridge had collected twelve sequential images capturing the horse in motion.

Those frames, or copies of them, could then be played in sequence using a zoopraxiscope to create the first moving image.

Personal cameras

The first cameras were bulky and the process for developing photos was complex. As a result, cameras and photography were largely the province of professional photographers. That changed in 1888 with the introduction of the Kodak #1.

The Kodak #1, ironically, was the second camera produced by the Kodak Eastman Company, (per Science Museum Group), but it was wildly more popular. Part of what made this camera so appealing was its simplified interface. The unassuming box housing removed some of the intimidation, but the real innovation was how the film was processed.

As explained by The Met Museum, the Kodak #1 came preloaded with enough film for 100 exposures. When the film was used up, the consumer sent the whole kit, camera and all, back to Kodak for developing. The company would then send the camera back to the consumer with a new roll of film while they were processing the initial images.

This took all of the hard work out of the hands of the consumer and allowed for the emergence of amateur photography, putting cameras into the hands of the average person.

35mm film

As the technology and the community around it evolved, cameras continued getting smaller and easier to use. While the Kodak #1 introduced the first popular personal camera, Oskar Barnack wasn't satisfied with their size or function. To that end, he set about inventing his own camera.

As explained by the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum, Barnack was interested in making smaller negatives which could then be enlarged to full-size finished images. By shrinking down the initial materials, cameras could become smaller and easier to use.

Barnack set his sights on 35mm movie stock as his film of choice because it was comparatively affordable and easy to get a hold of. In 1913 he succeeded in building his camera, what would come to be known as the Leica 1(A). However, it wasn't released to the public until 1925, (per the National Museum of American History).

Despite being nearly a hundred years having passed since its public introduction, it's easy to see the blueprint of modern cameras in the Leica. Its slim design and textured black finish wouldn't look out of place on today's store shelves.

The 35mm format was so successful it remains the standard for non-digital consumer cameras, even today.

Instant cameras

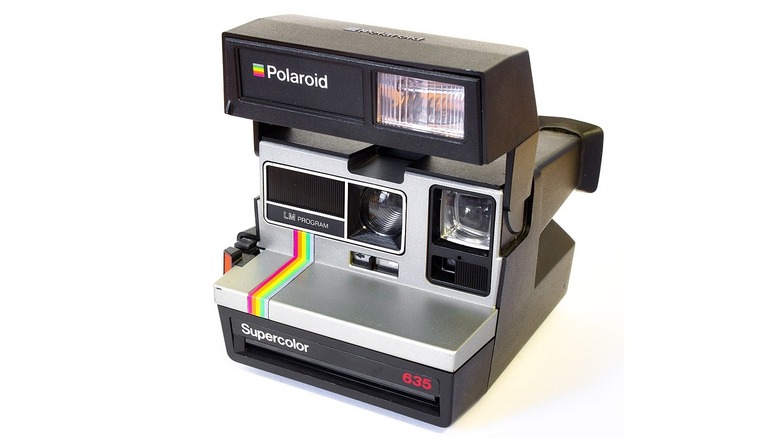

Edwin Land, the creator of the Polaroid camera, was interested in the science of optics from childhood but his first commercial ventures didn't involve cameras. That all changed on a family trip with his wife and daughter. During the trip Land was snapping photos of his family when his four-year-old daughter asked to see the pictures he'd taken.

The technology of the time required that film be sent back to the manufacturer for processing, and Land explained as much to his daughter. Still, Land reportedly had the idea for instant film immediately and quickly got to work. He spent the next few years developing the mechanics behind what would become the now-famous instant cameras that bear his company's name.

In 1948, the first instant camera was released to the public and they dominated the consumer space for decades. Leading up to the end of the twentieth century, Land continued to refine his instant cameras, enlisting the help of Ansel Adams and other well-known photographers of the time.

While instant cameras did eventually lose their market share to newer technologies, they cemented themselves as a central part of the evolution of photography.

Digital cameras

In 1975, Steve Sasson, an engineer for Kodak, invented the first digital camera. As explained by Wired, His first prototype was nearly the size of an over the shoulder boombox and was cobbled together from parts cannibalized around the office. The lens, which was taken from a Super 8 movie camera, captured images which were then converted to an electrical signal and recorded on cassette tape.

The technology worked but there were some considerable downsides. Sasson's "filmless photography" machine took roughly 23 seconds to capture an image. The tape then had to be removed and put into a customer device which displayed the images on a television. By this point people had become accustomed to swift exposures but might have been willing to overlook the timeframe if it weren't for the poor image quality.

The black and white images were mediocre even by the standards of the time, coming in at .01 megapixels, (per Kodak). For comparison, the iPhone 13 Pro's camera takes photos at 12 megapixels, a full 1200 times the resolution, and it does so instantly. Sasson would have had to capture images nonstop for nearly eight hours to capture the same amount of data you get while taking a selfie. Despite all those challenges, digital photography was destined to catch on.

Disposable cameras

Disposable cameras can trace their lineage back to Kodak #1's business model of sending the camera to the manufacturer to develop the photos. Beginning in the middle of the twentieth century a number of camera manufacturers began looking for a way to duplicate this process while making cameras cheap enough to be single-use. The first example of such a camera, dubbed the Photo-Pac, was created by H. M. Stiles in 1949, (per The Photography Professor). Legal controversy surrounding the company prevented the Photo-Pac from catching on long-term. It would be more than a decade before another disposable camera entered the market.

The French company, FEX, tried its hand at a disposable camera in 1966, (per the Museum of Obsolete Media) but it also didn't catch on. It seems the world, for a confluence of reasons, wasn't quite primed for cheap disposable photography, at least not until the mid-eighties.

As explained by Chem Europe, the disposable camera we've all come to know and love was developed by Fujifilm in 1986. This time, disposable cameras caught cultural fire. Their near-immediate popularity spawned copycats from a number of competitors including Kodak, who released their own 35mm disposable camera a few years later.

Camera phones

Prior to the emergence of camera phones, cell phones were actually mostly used as phones. They did include text messaging capabilities and rudimentary pixelated games, but the age of apps and internet connectivity hadn't yet turned cell phones into the all-purpose devices they are today. The addition of cameras into mobile phones was the beginning of that shift and it all started in June of 2000.

That year, Samsung released the SCH-V200 in South Korea. It included a .35-megapixel camera and enough storage to hold 20 photos. Getting the photos off the phone required connecting it to a computer, which may have made it less desirable, (per Digital Trends).

Later that year, Sharp released the first phone capable of taking pictures and sending them to someone else over the air. In 2002, camera phones finally made their way to the United States in the form of the Sanyo SCP-5300. Despite their inferior quality when compared with contemporary digital cameras, camera phone sales began outstripping that of digital cameras. By the end of 2003, roughly 84 million camera phones had been sold, making up approximately a sixth of all mobile phone sales, (per Financial Express).

From then on, an onboard camera became a pretty standard feature of cell phones. Today, you'd be hard-pressed to find a phone without one.

Modern professional cameras

Today, the ubiquity of cell phone cameras makes them the photography tool of choice for most people and they're perfectly suitable for most day-to-day picture and video taking. However, there's another world of photography if you really want to get serious about it.

While the camera in your pocket is convenient and smartphone cameras improved drastically over recent years, they don't get anywhere near the true capabilities of modern photography. Modern digital cameras, coupled with the vast array of lenses and accessories which bring out their true potential, can show you things from the microscopic to the far reaches of the universe. Moreover, they can do so in strikingly high definition.

The costs get pricey pretty quickly, and they only go up once you've caught the bug and find yourself buying additional lenses and filters, but it might be worth it for a camera you can literally see deep space with. We've come a long way since Niépce pointed that first camera out his bedroom window.