5 Things About Satellites They Didn't Teach You In School

More satellites are in our orbit than ever before. The number has jumped to over 11,000 as of May this year. Not only are there more satellites, they can do more things than ever, too. The space industry is changing quickly as technology and human needs change. From what they do in space to how they perceive the world around them, to what they do when they are about to collide, satellite builders are constantly pushing the envelope.

One example of this the direct connection between ordinary cell phones and satellites. Starlink started rolling out direct-to-cell capable satellitesin January 2024. The service has slowly become available across the world, with Europe getting its first connection only in November 2025. Verizon, working with satellite operator AST SpaceMobile, received authorization from the FCC to begin testing Verizon's direct-to-cell video service in January 2025. Here are some other things you might not know about satellites.

In-space manufacturing

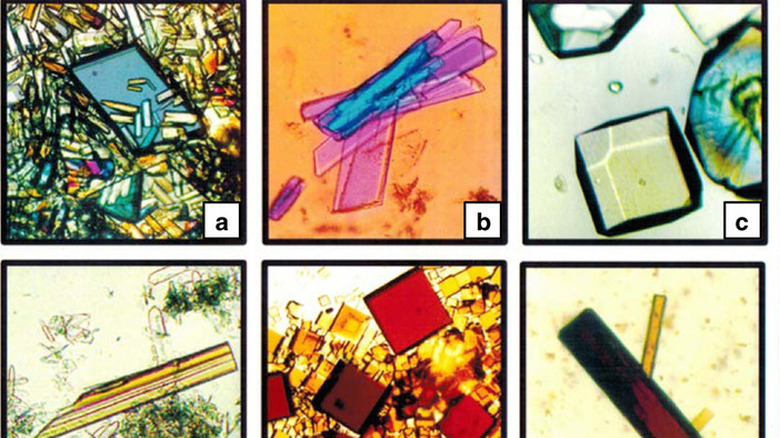

Experiments on board the International Space Station that include making things, such as synthesizing chemicals, have been going on for a long time. However, satellites are now being sent up by private companies to test manufacturing for things that cannot be made easily on Earth. The main problem with some manufacturing is that Earth's gravity can get in the way. Biochemicals and computer chips are just two areas that are being explored now.

In Spring an Summer 2025, Varda Space launched three satellites to test various parts of its system, such as the hardware of the satellite itself, but also to produce test-runs of small molecule crystals that would be used in the pharmaceutical industry. Space Forge, based in Wales, launched its first production satellite, ForgeStar-1, in June 2025, to test semiconductor manufacturing. The company is also testing a unique reentry heat shield they call Pridwen, after King Arthur's shield. Manufacturing in space is also changing how we handle the basics of satellite building and reentry.

Satellites can see through clouds, even at night

In 1946, a modified motion picture camera on a V-2 rocket launched from New Mexico took the first-ever picture from space. Clouds and night were a problem until the advent of Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), which depends on the movement of the radar to produce an image. SAR was first put into military satellites in the 1960s, but the resolution was poor. Development continued, however, and in 2018, Capella Space launched the first commercial SAR satellites.

SAR imagery has played an important role in showing the public how the Russian army was preparing to invade Ukraine and helped provide insights and intelligence on the war's impact. Maxar Technologies provided imagery that cut through snowstorms to show troop movements. Governments and companies quickly caught onto the possibilities that SAR raises and now the technology is used for quickly assessing the aftermath of disasters no matter what time of day or how stormy it is.

Trains, then constellations, now swarms

At first, satellites were launched singly — like the first Sputnik satellites — and one satellite would be in an orbit on its own. Later satellite trains, or groups of satellites moving in a single line, began to be used for applications such as Internet access to improve access from the ground. At the same time, constellations of satellites, such as GPS, widened coverage on Earth with greater distances between them and without being in a line. However, constellations are relatively fixed. Even if the satellites are moving at different speeds and in different orbits, their relative positions are predictable.

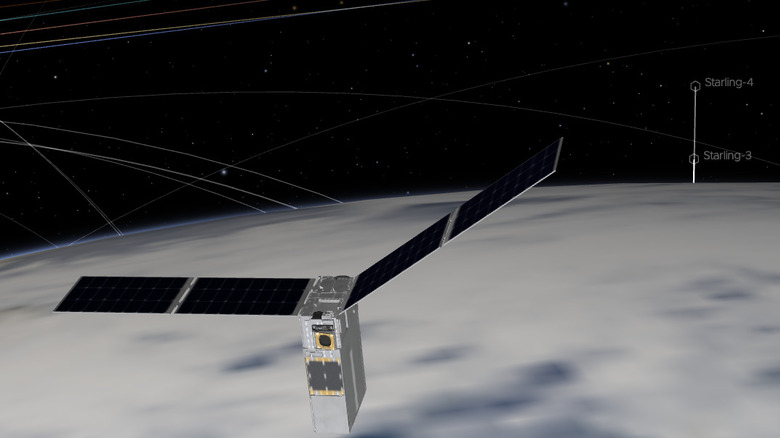

Now, groups of satellites are beginning to move as a swarm. NASA tested the ability of a group of satellites to autonomously communicate and coordinate when each of its members should move. Satellites need to change their orbits more than they used to in order avoid other currently active satellites as well as space junk such as defunct satellites and parts from spacecraft that were hit by meteors.

Independent collision avoidance

The need to move as a swarm makes predicting a satellite's next movements difficult. Space Situational Awareness, or SSA, is necessary to understand when a satellite is in danger of colliding with another object. With SSA, decisions on orbits can be made, but the time that it takes to send data to Earth, analyze it and return a command could be long enough for the satellite to end up on a collision path. Starlink, for example, uses an automated collision avoidance system, but operators on the ground are still in the loop.

Instead, satellites that can make orbital decisions on their own are now being tested. The NASA STARLING project tested how to handle the interaction between satellites and ensure that they do not collide with each other. Unlike existing systems, there will be no human in the data collection service. Also, to save time, satellites will begin to wholly source the data they use from their own and other satellite. This will also cut the time between obtaining information and acting on it.

Sateliltes are gaining X-ray vision

If you count being able to see X-rays emitted by a star as X-ray vision, then satellites have had it for a long time. Such satellites are X-ray telescopes that further our knowledge about the universe. However, the Superman version, as in being able to see inside something, is a new addition to some satellites' capabilities.

ThinkOrbit announced in 2025 that it would be launching a satellite that can use x-rays to look inside other satellites. This capability was described as important for monitoring threats in space as political tensions are increasing in the space race. At the same time, satellite X-ray vision will be helpful in understanding why a satellite stopped working, and whether it is malfunctioning or has been pierced by a piece of space junk. Repairing a satellite in space is something that has been done before, such as when the Hubble Telescope had its 'vision' corrected, but this adds a new layer to diagnosing a "sick" satellite.