This Medical Device Can Extend People's Lives (And Was Invented Entirely By Accident)

Today's pacemakers are about the size of a small matchbox, and future models are expected to shrink even further, becoming smaller than a grain of rice. Now, these devices, depending on the model, can last as long as 10 to 15 years before needing replacement and can automatically adjust based on a patient's activity level. They can now connect to the internet and transmit real-time data to physicians, without patients even coming into the hospital. And with how close we are to AI superintelligence, future pacemakers might be able to predict complications before they occur or optimize pacing algorithms based on individual heart patterns.

Interestingly, the pacemaker wasn't always as small and efficient as it is today. Early artificial pacemaker machines were about the size of a bedside cabinet and had to be plugged into wall outlets to run. As you can imagine, if there was any power outage, the system would go off. So, although they could pace a heart, they were painful, very uncomfortable, and often unreliable. At the time, there were three major problems with those early artificial pacemaker machines: power source, portability, and implantability.

Earl Bakken, a medical equipment repairman in Minneapolis, fixed the first two. He created the first battery-operated, wearable pacemaker at the request of surgeon C. Walton Lillehei. About the size of a paperback book, patients wore it around their necks while wires passed through their chest from open-heart surgery. While it was a significant leap forward, the device left patients vulnerable to infections through the external wires. As for implantability, that was a solution Wilson Greatbatch discovered entirely by mistake.

The lucky accident that transformed cardiac care

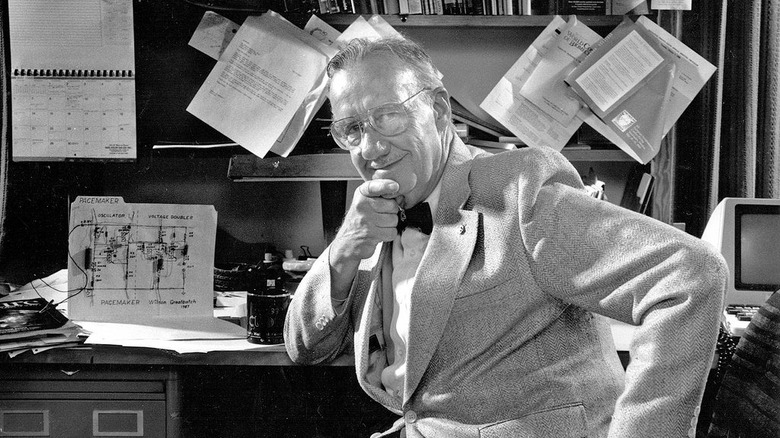

Wilson Greatbatch, an electrical engineer teaching at the University of Buffalo, New York, was building a device to record heartbeats. While assembling the circuit, he grabbed the wrong resistor from his toolbox. He inserted a 1-megohm resistor instead of a 10,000-ohm one. When he powered up the circuit, instead of recording, it emitted rhythmic electrical pulses at roughly one per second. Greatbatch immediately recognized what he was hearing.

He later recalled: "I stared at the thing in disbelief." The pulses matched a human heartbeat. He went to meet Dr. William Chardack and Dr. Andrew Gage, two cardiac surgeons at the Buffalo Veterans Hospital, to test the accidental invention. On May 7, 1958, they connected it to a dog's heart, and it worked perfectly. They continued to refine the design and in June 1960, implanted a unit in a 77-year-old with complete heart block. The patient lived two more years and died of natural causes.

As miraculous as that breakthrough was, it was still far from perfect. There were still major problems with the batteries, casings, and surgical procedures for implanting them. Nonetheless, this discovery remains one of the tech inventions that changed the health industry forever. Piece by piece, engineers and doctors have worked tirelessly over the following decades to find long-lasting workarounds to these problems. So far, more than 3 million people across the world are living with pacemakers today, with roughly 600,000 new devices implanted each year. Just imagine if Greatbatch had beaten himself up for using the wrong resistor and completely dismissed the error. Maybe someone else would have found it eventually, but who knows how long that would have taken?

Why does the heart need a pacemaker?

Naturally, your heart comes with its own in-built pacer called the sinus node. It fires tiny electrical signals that keep your heartbeat steady. But when that system fails, the heart starts to beat either slowly or abnormally—a condition generally known as arrhythmia— which, according to research, affects 1 in 18 Americans. Unfortunately, when the heart doesn't beat well, other parts of the body are unable to function properly.

For centuries, scholars had a rough hunch that electric currents could play a part in regulating extreme medical conditions. In Ancient Rome, there are records of physicians using electric fish to jolt patients, but as you can imagine, these treatments didn't make much of a difference. And that meant that for most people with severe forms of arrhythmia, there weren't a lot of options. If they were born with it, they either died very young or, as adults, lived painful, difficult lives.

As science evolved, doctors developed a relatively better understanding of cardiac rhythm. But like we said before, early artificial pacemaker machines from the 1950s weren't practical at all, until that lucky accident in Greatbatch's workshop. His willingness to see potential in a mistake, rather than treat it as a setback, helped transform cardiac care and give hope to millions who are now able to live longer, happier lives. Today, people with pacemakers can travel, exercise, and go about their daily routines without constant fear of their hearts failing. Interesting, isn't it, how some of the most useful tech in our lives today was made by accident, from penicillin to microwaves and even tech as sophisticated as the pacemaker.