France Just Set A Nuclear Fusion Reactor World Record - And Here's How

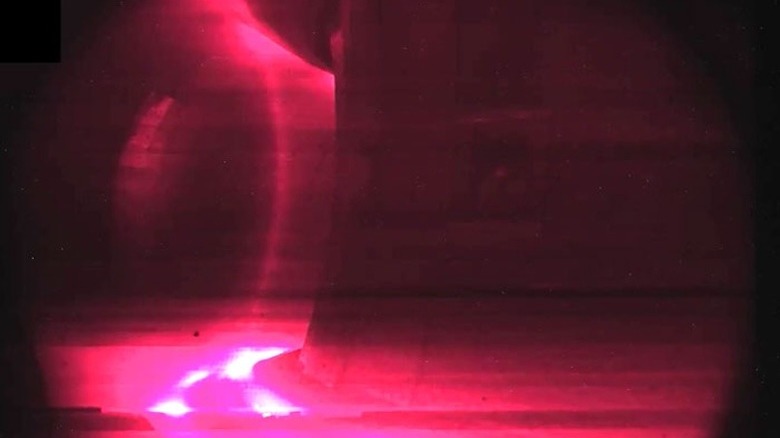

In February, France's WEST nuclear fusion reactor made a big step toward getting clean, star-like energy for everyone. The machine held superheated plasma for 1,337 seconds, or just over 22 minutes. This broke the previous world record set by China's EAST tokamak a few weeks earlier. That's a 25% improvement, a huge leap forward when you consider that keeping plasma under control for long periods of time is one of the hardest things to achieve in the world of science.

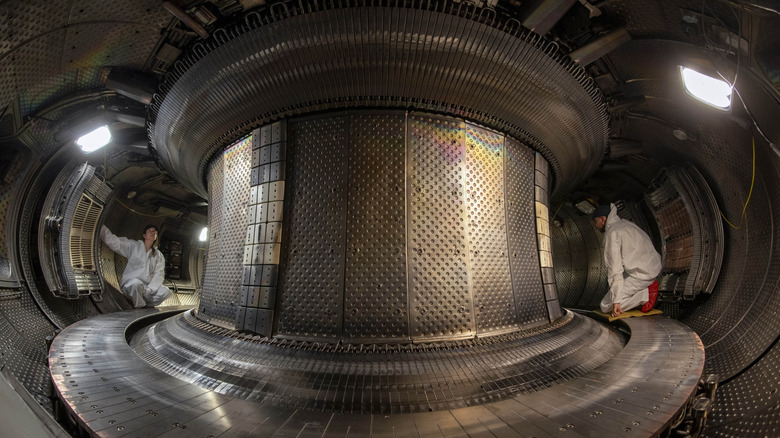

Anne-Isabelle Etienvre, director of fundamental research at the Commissariat à l'énergie atomique et aux énergies alternatives (CEA), called the achievement "a new key technological milestone." At its core, WEST used a few megawatts of heating power and powerful magnetic fields to keep hydrogen plasma at 50 million degrees Celsius, corralled inside a torus-shaped vessel.

The breakthrough demonstrates that the machine's tungsten walls and cooling systems can withstand the punishing conditions of extended plasma operation without breaking down. While WEST isn't designed to produce net power, the record shows that fusion devices can now sustain the kind of stability a future energy plant will need.

How a tokamak tames a star

Tokamak nuclear fusion machines, such as WEST, send charged particles in guided infinite loops around a doughnut-shaped chamber, which acts as a magnetic bottle. Normally, the plasma would immediately cool the reaction and harm the apparatus if it were to strike the walls directly, but this magnetic confinement keeps it from happening. It's incredibly difficult to achieve this balance, as plasma is infamously unstable, and even minor imbalances can cause major problems.

The WEST experiment used about 2 megawatts of continuous heating to keep the plasma alive while carefully managing exhaust particles and heat loads on its tungsten divertor region. Even though tungsten can withstand high temperatures, researchers still had to keep contamination and erosion at bay. WEST's ability to retain plasma for over 20 minutes in these circumstances indicates that its components worked as intended, boosting confidence levels in next-generation designs like ITER, the much larger international tokamak with a 60-foot magnet at its core that's currently being assembled in the same area of southern France.

ITER aims to scale this work up dramatically, targeting 500 megawatts of fusion power output from just 50 megawatts of heating. Data from WEST will directly inform how engineers prepare for ITER's first plasma runs.

Why long plasma runs are the real prize

Nuclear fusion breakthroughs often make headlines for record temperatures or net-energy experiments, like the U.S. National Ignition Facility's 2022 milestone or the U.K.'s Joint European Torus generating 59 megajoules over five seconds. WEST's achievement is different: instead of raw power output, it demonstrated longevity and resilience. A practical power plant will need to operate continuously for hours, days, and eventually years at a time without catastrophic damage to its components.

That's why the 22-minute run is significant. It shows that not only can plasma be confined at extreme heat, but reactor surfaces and cooling systems can survive the stress for meaningful periods. Longer campaigns at WEST are planned, with the ultimate goal of running plasmas for hours while gradually increasing heating power. These experiments will refine the operational "playbook" for ITER and beyond.

Fusion energy still faces hurdles — like managing activated reactor materials and maintaining the cleanliness of the plasma environment — but WEST's progress offers a critical proof of concept. Each record, whether in power, duration, or stability, builds the foundation for machines that will be the breakthrough for nearly limitless clean energy, mimicking the reactions that light up the stars.