Earth's Umbrella: How A Solar Shield Tethered To An Asteroid Could Fight Climate Change

Among the many extra-terrestrial challenges faced by the Earth, one of them comes straight from our planet's home star. Sun eruptions mainly come in two forms: solar flares and coronal mass ejections. The origin story is identical in both cases, but the former travels at the speed of light and mainly consist of high-energy particles, while coronal mass ejections (CME) are essentially a magnetic cloud that travels slower but can wreak havoc on electrical and telecom infrastructure.

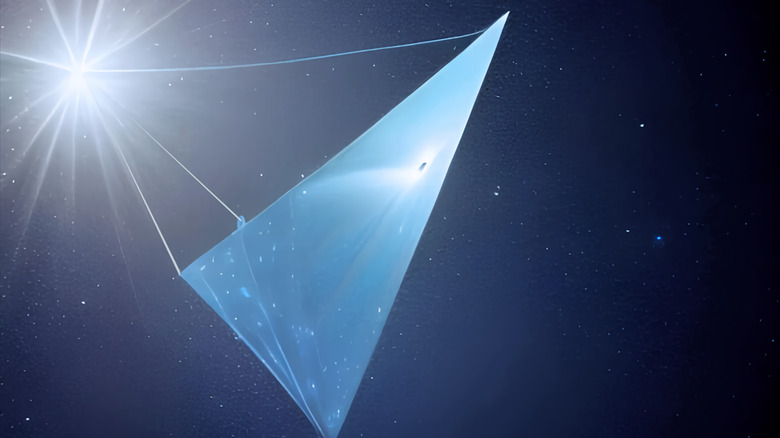

Then there's climate change phenomenon, which has compounded the harmful impact of solar radiations. So far, scientists have proposed a diverse gamut of ideas — ranging from seemingly practical to downright wild — that seek to protect Earth from a potential major solar catastrophe. The latest one comes from experts at the University of Hawaii, and it proposes creating a massive umbrella tethered to an asteroid.

The contraption would act as "a solar shield to reduce the amount of sunlight hitting Earth." To begin with, the team has set a target of blocking about 1.7% of solar radiation falling on Earth, which is said to be enough to stop "a catastrophic rise in global temperatures."

Another advantage of this approach is that it is fairly non-invasive compared to other geo-engineering ideas that consider chemically or physically altering the Earth's atmosphere and seas. But as clever as it sounds, there are still practical challenges.

Why an Earth umbrella?

While mitigating climate disasters like global warming is the eventual goal here, there are also immediate benefits. The Earth's home star exhibits a variety of abnormal activities from time to time, some of which can be devastating. Two of them happen to be solar flares and coronal mass ejections. Solar flares aren't particularly destructive, as they are known to only disrupt the exposed region of the atmosphere. It can affect telecom activities and cause disruptions to GPS satellites, leading to temporary accuracy issues that throw location readings by a few yards.

But it's the coronal mass ejection that can do some serious damage. Think of them as a powerful gun of an electromagnetic pulse that can blow out transformers in the power grid. It can shut down cell towers and severely impact communication networks, wiping out critical contact channels, essentially creating a blackout.

There's already some precedent for it. In 1859, a geomagnetic storm stirred by an eruption of charged particles hit the Earth. Also known as the Carrington Event, it sent a charge streaming down telegraph lines that shocked operators and even lit paper on fire. If a similar event happens today, it could fry the modern infrastructure consisting of power stations and transmission line networks. But it's not just the damage that is worrisome to imagine. If the eruptions are intense, a solar superstorm could up doing trillions of dollars worth of damage and lead to human casualties.

How a space umbrella would protect Earth?

In order to create a shield of sufficient mass that is capable of counter-balancing the gravitational pull and effectively counteract the solar radiation pressure, a massive weight is required. This weight, however, is an engineering challenge because the cost associated with the acquisition and utilization of even the lightest materials becomes prohibitively expensive.

To overcome the weight challenge, the team proposes only a fraction of the shield assembly is transported from Earth, while the rest is provided by an extraterrestrial object, like an asteroid. The asteroid would act like a ballast, stabilizing the entire umbrella assembly. "Such a tethered structure would be faster and cheaper to build and deploy than other shield designs," says the team at the University of Hawaii.

Once in space, the shield would slowly open in a petal configuration. The team proposes using solar-charged winches to increase or decrease the length of the tethers to handle solar and lunar wind's destabilizing effects. But the research paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences mentions that even for achieving the initial radiation-blocking goals, multiple solar shields would be more effective.

As for the build material, the team is banking on graphene, a carbon-based material that is lauded for its unprecedented toughness, flexibility, resistance, and most importantly, lightweight nature. Even though it's expensive, the team is hoping that costs could come down drastically later in the decade.

Still deep into the future

As promising as the idea sounds, it is nowhere near ready for deployment. Despite reducing the lift-off load by 99% to create a sun shield, the 1% that needs to be injected into space is massive. Approximately 35,000 metric tonnes of sun shield gear, to be specific. There is no rocket launch vehicle out there that can even remotely match those payload figures.

Starship, which is claimed to be the world's most powerful launch vehicle, still falls short. In its reusable form, it can deliver a payload of 150 metric tonnes, going up to 250 metric tonnes if deployed with an expendable approach. NASA's Saturn V, one of the most powerful heavy-lift launch vehicles ever made, could only reach around 141 metric tonnes.

Even if one takes into account the possibility of multi-stage payload injection, it would take no less than 233 Starship missions to deliver the full sun shield payload into space. That won't be easy on anyone's bank account. Elon Musk said in 2022 that each Starship launch could cost as little as a million dollars, down from the $2 million per launch figure he quoted in 2019, and significantly lower than the $10 million launch cost he threw around last year.

While the project is challenging and beyond the might of current-generation launch vehicles, the team says their approach "brings the idea into the realm of possibility, even with today's technology, whereas prior concepts were completely unachievable."

How do you capture an asteroid?

Another key challenge would be asteroid capture. So far, NASA has demonstrated that it can divert an asteroid if need be, thanks to the successful test of the DART mission. Multiple missions, such as JAXA's Hayabusa-2 have been able to land on an asteroid and collect surface material. However, capturing an asteroid, and manipulating its natural trajectory so that it can be put in the right lunar orbit hasn't been attempted before.

The paper talks about "asteroid orbit manipulation" because that's what they plan to use as the source of the ballast material to act as a counterweight. But even NASA has pulled itself from making such an attempt. The space agency worked on the Asteroid Redirect Mission, which involved creating a massive space robot that takes a multi-tonne boulder from an asteroid and parks it in the moon's orbit. However, as part of the White House Space Policy Directive (2017), the project was shelved.

So, what's the alternative? Lunar dust. But once again, that would require active operations from the Lunar surface, which is currently not happening at the scale required."The shield has enough weight to wreak havoc if it accidentally crashes on Earth," adds the research paper. Experts predict that if one or two tethers give up, no major accident would happen. However, if more tethers were to break, the entire structure would collapse and careen towards the sun, while the threat to Earth is negligible.

What else is happening to shield Earth?

Over the past few decades, global warming has wreaked climate havoc in varied ways, raising the average global temperature to record levels and posing a serious threat to Earth's biodiversity. Emissions keep rising despite efforts, so scientists have turned their heads to a more ambitious domain called Solar Radiation Management — or solar geo-engineering — which involves somehow limiting the amount of sunlight that the Earth is exposed to.

These ideas include everything from spraying aerosols high in the stratosphere that create a shied to installing a giant mirror reflector in space. Take for example the proposal for aerosol injection, which aims to use sulfur compounds, in order to cool down the global temperature and potentially restore worldwide rainfall patterns, but not without serious risks.

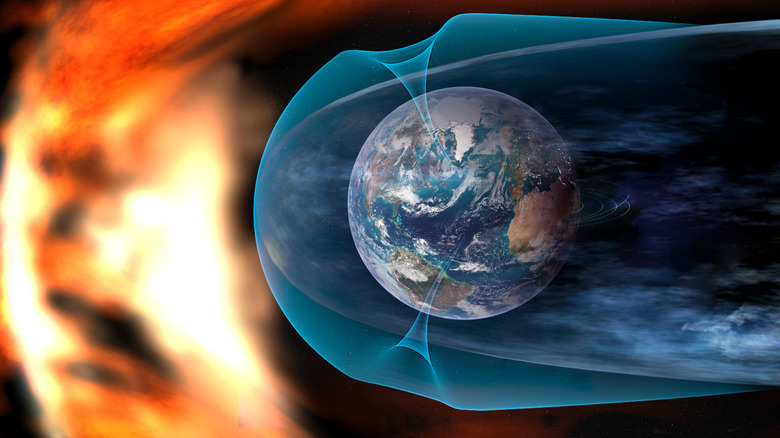

Next in line is the concept of "marine cloud brightening," which involves spraying seawater into the sky to create white clouds that would reflect the incident sunlight. A similar proposal wants to create an "ocean mirror" using micro-bubbles generated by sea vessels over a large oceanic surface. Another proposal that comes from Cornell University experts considers setting up a magnetic shield to deflect charged particles coming from the Sun.

However, none of them have been attempted so far on a scale large enough to produce a tangible results towards saving the Earth from environmental disaster. The space umbrella idea pushes itself as one of the most practical and least risky ideas to save our planet.