The Messine Mine: The Largest Blast Of WWI Explained

The late July release of Christopher Nolan's blockbuster "Oppenheimer" brought increased attention to some of the most dangerous military weapons used to wage war, particularly the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki that were critical in bringing World War II to an end.

But nearly three decades before Oppenheimer's first bombs were detonated over Japan and thousands of miles away from those sites, a massive Allied undertaking during World War I in Belgium led to a cataclysmic explosion that is regarded as the largest in the pre-nuclear era and killed thousands of German soldiers. The early-morning blast was loud enough to be heard by the British Prime minister 140 miles away in London.

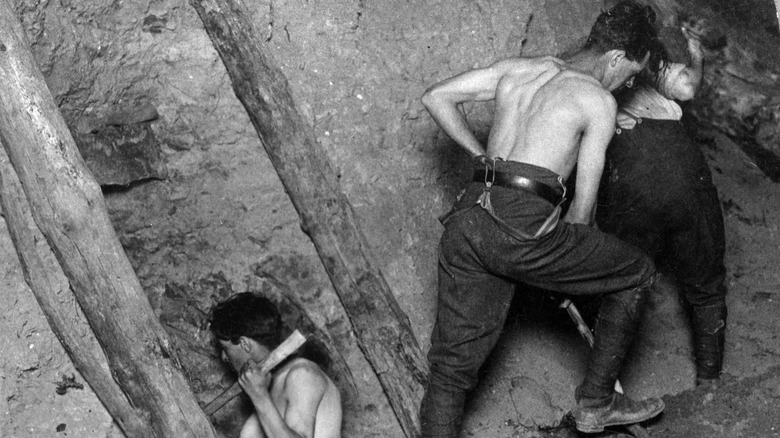

To prepare for the attack, Allied soldiers spent two years digging a network of tunnels nearly 100 feet deep under the Messine ridge, including a series of decoy tunnels which the Germans wasted time and effort attacking. Many of the Allied soldiers who were used to dig the shafts and tunnels brought relevant civilian experience to the wartime project.

New Zealand historian Ian McGibbon told History.com, "Most of the tunnelers were coal miners or gold miners very experienced at digging. The idea was to get under your opponent's lines and explode mines. It was a very nerve-wracking experience, especially when you approached their lines and knew that the enemy might explode a mine near your shaft to destroy it."

The subsequent battle claimed thousands of Allied lives as well

The massive tunneling effort was a move to break a costly stalemate that had developed near the town of Ypres early in the war. By summer of 1917 the digging project was complete and roughly 1 million pounds of ammonal — a combination of ammonium nitrate and aluminum powder — had been placed underground. Just after 3 a.m. on June 7, 19 of the 22 mines were detonated, setting off a mushroom cloud that British artillery officer Ralph Hamilton compared to the famous battle at the Somme that killed 20,000 British troops in a single day. "First, there was a double shock that shook the earth here 15,000 yards away like a gigantic earthquake," Hamilton wrote. "The whole country was lit with a red light like in a photographic dark room. The noise surpasses even the Somme; it is terrific, magnificent, overwhelming."

After the giant explosion, Allied troops advanced behind a wall of artillery fire, and the Germans quickly surrendered. "As the troops are advancing, there's a curtain of fire coming down 50 yards in front of them," McGibbon said. "It must have been a fearsome experience for the Germans, seeing this coming toward them."

Although the Allied troops were able to take the ridge quickly after the explosion, the Germans launched a counterattack during the next two days that took thousands of lives, although the Allies kept control of the ridge.