Hiller X-18: The Strange-Looking Cargo Aircraft That Would Lead The Way For VTOL Technology

Aircraft capable of Vertical Takeoff and Landing, or VTOL, have always captivated aviation enthusiasts with their strangeness and militaries with their versatility. However, the fact that their counterparts — conventional planes and helicopters — tend to meet most commercial and military requirements means they can be quite rare. To this day, the US's V-22 Osprey, introduced in the 2000s and the first and only tiltrotor aircraft in production, is instantly recognizable with its massive tilting rotors at each wingtip.

However, the interest in VTOL aircraft predates the V-22 by well over 50 years, and throughout their development, VTOL aircraft have taken many strange and interesting forms. They include tail-sitters like the Convair XFY Pogo and Ryan X-13 Vertijet, gyrodynes like the Fairey Rotodyne, and more traditional convertiplanes like the Hiller X-18, as well as its descendant, the V-22 Osprey.

While the other forms of VTOL aircraft never went beyond testing, convertiplanes have shown some promise, with the development of both tilt-wing and tiltrotor aircraft continuing to this day. In this field, the Hiller X-18 was the first of its kind and an incredible aircraft, especially for its time. So here's all you need to know about the world's first tilt-wing VTOL aircraft, the Hiller X-18.

The requirement

In the 1950s, the US Air Force was interested in developing a VTOL aircraft and awarded a contract to Hiller Aviation, already known for their work with helicopters, to develop an experimental vehicle.

Hiller was tasked with building a VTOL aircraft that could carry a total payload of 8000 lbs, including 35 combat troops or vehicles and equipment of equivalent weight, have an operating radius of 425 miles, a cruise speed of 300 mph, and the ability to hover at 6000 ft. It was also supposed to be controllable in the event one engine failed and be able to make a "controlled crash" landing.

While the initial plan called for a four-engine aircraft, the X-18 was designed to have only two, most likely because it was a test platform for tilt-wing VTOL technology and not a production vehicle. Such a vehicle, the Ling-Temco-Vought XC-142, would later be developed and tested based on the insights gathered from the X-18 program.

Building the X-18

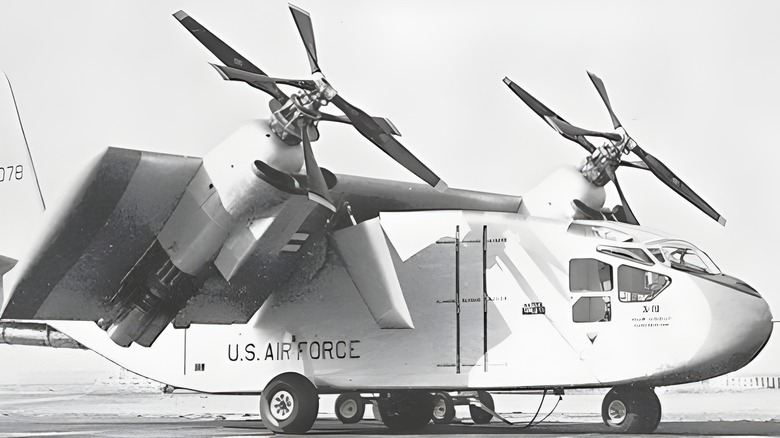

To save time and money, Hiller adapted many critical components from other existing aircraft. The fuselage was taken from a Chase YC-122 Avitruc, a cargo aircraft already in use with the U.S. military, though Hiller had to cut the fuselage in two and lengthen it to build the X-18. This was done to make sure the experimental aircraft's center of gravity and landing gear were in the correct locations, as it was a significant departure from the YC-122 on a mechanical front.

Furthermore, Hiller chose engines and propellers already used in different VTOL testing programs for the X-18. The two Allison T40 engines and the contra-rotating triple-blade propeller setups attached to each were taken from the experimental Lockheed XFV and Convair XFY Pogo tail-sitter aircraft. While loud, having two propellers mounted to each engine and spinning in opposite directions provided the significant thrust and efficiency needed to achieve vertical takeoff and landing capability. Each propeller was also a massive 16 feet across, leading to the aircraft being called the Propelloplane.

Though it looked like a twin-engine plane, the Hiller X-18 actually had three — the two Allison turboshaft engines on the wing provided thrust, and a separate Westinghouse turbojet inside the rear fuselage, which was used to control pitch when the aircraft was operating in VTOL mode by having its thrust diverted through a pipe protruding out the back of the aircraft.

The tilting wing

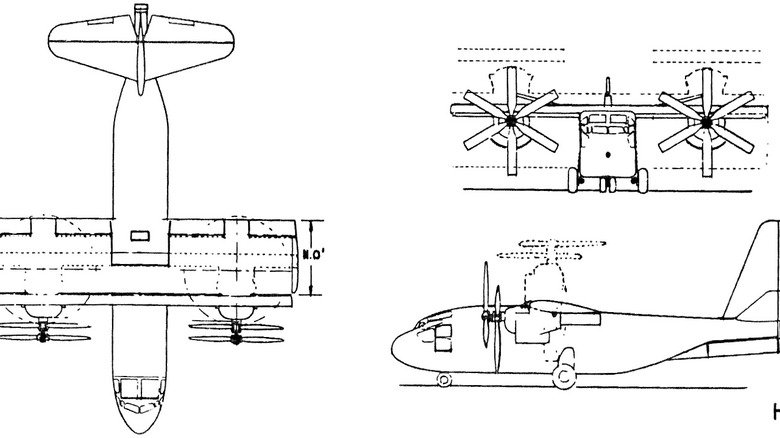

There are a few different approaches to achieving VTOL capability. For instance, the Harrier jump jet used rotating ducts to direct thrust from its jet engine for takeoff and landing. The F-35B uses a combination of thrust vectoring at the rear and a large fan closer to the front of the plane for vertical landing. Meanwhile, aircraft which rely on propellors generally follow one of two designs. They can either be designed to tilt their rotor assemblies, as the V-22 Osprey does, or to tilt the entire wing to which the rotors are attached, which was the approach taken by the Hiller X-18.

The X-18 relied on a pair of hydraulic pistons to rotate the wings up to 90 degrees, allowing it to take off and land vertically like a helicopter and then transition to level flight like any other cargo plane. Unlike a tiltrotor aircraft, the X-18 could transition from vertical to horizontal flight by simply rotating the wing. In comparison, tiltrotor aircraft must fly forwards like a helicopter before returning their engines to a horizontal orientation to create sufficient airflow over the wings to generate lift.

Tilting the entire wing did present one significant drawback — when oriented vertically, the wing would act more or less as a sail, making the X-18 highly susceptible to winds when landing and taking off. This did not lead to any crashes but could have if the plane had made it out of development and into production.

Testing and ending the program

Only one X-18 was ever built, with testing primarily taking place at Edwards Air Force Base, where 20 test flights were conducted from 1959 to 1961. Throughout these tests, it achieved a top speed of 253 mph and reached an altitude of 35,300 feet. Despite these achievements, the aircraft also presented some significant issues. For instance, the failure of a single engine would have been catastrophic, as the engines were not interconnected — modern aircraft such as the V-22 Osprey has a driveshaft connecting the two engines, allowing either engine to power both propellers in the event one engine fails. Flight testing was suspended after an incident during a 1961 test of the aircraft's hovering capability where the aircraft entered a spin at 10,000 ft. This occurred due to an issue in pitch control on one of the propellers, causing it to lose thrust on one side. The aircraft was thereafter restricted to ground testing.

The X-18 was then used to test the impact of ground effect on VTOL aircraft until a failure of the test stand damaged it — the aircraft was scrapped afterward. The learnings from the X-18 program were later used to develop other tilt-wing aircraft. One of them is the Ling-Temco-Vought XC-142, a four-engine aircraft that successfully transitioned from vertical to horizontal flight. The insights from this program have also since played a major role in the development of modern VTOL aircraft.