Why Nintendo Doesn't Want You Using Emulators To Play Its Games

If you've been keeping up with the headlines on video game websites, then you may have seen how Nintendo struck the latest blow in its longtime war on fan-made emulators of its consoles. Most recently, Nintendo of America filed a federal lawsuit in the District of Rhode Island against Tropic Haze LLC, the company behind Yuzu, a Switch emulator. The Tropic Haze/yuzu team, seemingly seeing themselves as no match for Nintendo's lawyers and unlimited resources, quickly folded, officially agreeing to a $2.4 million settlement a week later.

Of course, the case is more complicated than Nintendo suing over the development of an emulator. Emulators themselves are entirely legal; where it gets murky is when unauthorized copies of software are brought into the mix. That doesn't just refer to games; the BIOS for a console qualifies as copyrighted software, as well. Providing tools that break copy protection are another way to run afoul of the law, while charging for your emulator is a sure-fire way to raise Nintendo's ire even if everything that you're doing is legal.

With that in mind, let's take a look at Nintendo's history with emulation — as opposed to its own fascinating history — the company's official comments on the matter, its past related legal action, why it singled out Yuzu, and why some gamers view the company as a bunch of hypocrites.

Why do gamers use emulators?

First, gamers use emulation, as well as hacks to run unofficial code on consoles, for much more than just playing illicitly downloaded copies of commercially available games. Yes, it happens, and it's widespread, but it's much more complicated than that with a wider scope.

You can run homebrew software, but your mileage may vary as to if the average gamer has any interest in that. And while we've seen an uptick in the number of classic game releases in the Internet-connected console era, those releases represent only a small fraction of what's out there. As much as digital downloads have made it significantly easier to distribute classic titles and lower the overhead required that could be allocated elsewhere, like licensing fees for outside IP, modern re-releases like "The Disney Afternoon Collection" are the exception much more than the rule.

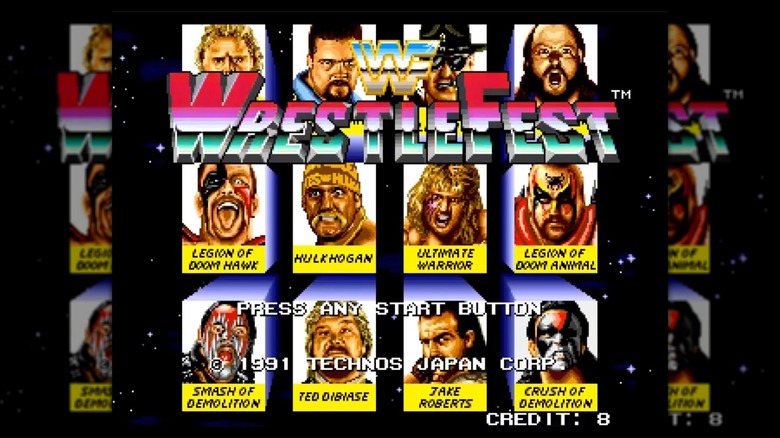

Take, for instance, the 1991 arcade game "WWF WrestleFest" from Technos Japan. It's arguably the best pro wrestling video game of that era to carry a WWF license and maybe even the best wrestling-themed arcade game ever made. But it never got a home release, presumably thanks in part to different companies holding the WWF console and home computer licenses. The only way to play it without an original arcade cabinet is by using an emulator, and it's far from the only game like this, to say nothing of games from publishers that no longer exist and haven't had their IP acquired.

What is Nintendo's official stance on emulation?

Nintendo has taken a pretty firm stance against unofficial emulators for decades. The most detailed version of that stance would probably be the "legal information page" that was formerly on the company's corporate website and has been preserved by The Internet Archive's Wayback Machine.

"The introduction of emulators created to play illegally copied Nintendo software represents the greatest threat to date to the intellectual property rights of video game developers," Nintendo stated. "As is the case with any business or industry, when its products become available for free, the revenue stream supporting that industry is threatened. Such emulators have the potential to significantly damage a worldwide entertainment software industry which generates over $15 billion annually, and tens of thousands of jobs."

What about games that are no longer commercially available, you ask? Nintendo knew you'd go there.

"The problem is that it's illegal," Nintendo wrote. "If these vintage titles are available far and wide, it undermines the value of this intellectual property and adversely affects the right owner." Nintendo then asked itself the same basic question, phrased slightly differently.

"No, the current availability of a game in stores is irrelevant as to its copyright status. Copyrights do not enter the public domain just because they are no longer commercially exploited or widely available. Therefore, the copyrights of games are valid even if the games are not found on store shelves, and using, copying and/or distributing those games is a copyright infringement."

Why did Nintendo single out yuzu?

One thing that's clear is that the lawyers for the producer of the immensely popular Nintendo Switch had prepared for the common counter-arguments about why emulation is legal. The same goes for backing up your legally purchased games for personal use, which is explicitly allowed under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

"Any copy of a Nintendo Switch game ROM not on an authorized cartridge or console is an unauthorized copy and therefore infringing," reads the complaint. "Copies played in Yuzu would otherwise have to be purchased if Nintendo offered its games on the PC platform. As the copyright owner of its creative games, Nintendo has the right to decide whether or when to enter the market of games for platforms other than its own console, both with respect to its current and forthcoming games and with respect to any game in its legacy collection."

Regardless, Nintendo did not argue that Yuzu was being used to directly circumvent copy protection, since it doesn't. Instead, Nintendo's lawyers noted that the emulator's official documentation instructed users on how to obtain the "prod.keys" from their very versatile Switch consoles to allow them to decrypt Switch games in Yuzu. This, they said, qualified as circumventing copy protection under the DMCA.

Nintendo also argued that Digital Haze was benefitting from illicit downloads and knew it. Specifically, when "The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom" leaked 11 days early on May 1, 2023, membership to the Yuzu Team Patreon page doubled.

Is Nintendo saying all emulators are illegal?

Informally, Nintendo suggests that all fan-made emulators are illegal because, in the company's view, they're inextricably linked with illicitly obtained game ROMs and disc images. Federal courts have been consistent that an emulator without bundled BIOS, cryptographic keys, etc. is legal, but Nintendo seemingly ignores those precedents by framing all emulators as copyright circumvention apps.

"A video game emulator is a piece of software that allows users to unlawfully play pirated video games that were published only for a specific console on a general-purpose computing device," wrote Nintendo's lawyers in the complaint against Tropic Haze. This, of course, is not an accurate definition of what an emulator is, particularly since official emulators are not being distinguished from fan-made emulators. But that also wasn't Nintendo's legal argument against Yuzu; it was just framed as background information in the lawsuit.

It's unlikely that Nintendo would test this definition in court. Barring 1999 threats to UltraHLE, a Nintendo 64 emulator, before courts ruled emulation legal, Nintendo only targeted specific emulators that were arguably circumventing copy protection. The only non-Yuzu emulator that the company has gone after is the GameCube and Wii emulator Dolphin, which includes the Wii's common cryptographic key, but that wasn't a lawsuit — just a warning to Steam, which gamers have used for emulators. In a May 2023 statement, Nintendo said, "Using illegal emulators or illegal copies of games harms development and ultimately stifles innovation," but did not distinguish what "legal emulators" would be.

Why do some gamers view Nintendo as hypocritical?

One factor in Nintendo's public approach to emulation is that it can easily be argued that the company is hypocritical. As PC Gamer and The Verge noted in May 2023 and March 2024, respectively, not only does Nintendo develop its own emulators to run classic games on its newer hardware, but it also hired developers from the fan emulation community to work on those in-house emulators. It doesn't help perception, either, that, as the PC Gamer article notes, Nintendo's lawyers have perhaps unknowingly given inaccurate information about emulation, like claiming that the Dolphin emulator broke GameCube encryption that didn't exist.

Perhaps most infamously, though, there was a topic first broached to a wide audience in a 2016 Game Developers Conference presentation given by Frank Cifaldi, Digital Eclipse's Head of Restoration. Specifically, Cifaldi pointed out that, if you dig into the code of the Nintendo Wii Virtual Console version of "Super Mario Bros.," you'll find the presence of a .NES header. This is notable because Marat Fayzullin created the header for iNES, a Nintendo Entertainment System emulator that he released in 1996, suggesting that Nintendo used a fan-dumped ROM downloaded online for its official release.

In January 2017, Eurogamer looked into this further and consulted Fayzullin. He extracted the ROM, compared it to known dumps online, and concluded they were identical. Nintendo didn't comment when reached by Eurogamer.