What The Linux Desktop Must Have To Become Mainstream

Linux runs the computing world. It is by far the most used operating system on servers and perhaps the only OS on supercomputers. It has taken over much of the mobile world thanks to Android and is on the cusp of taking a majority share in education via Chrome OS.The one area where it has had difficulty expanding year after year is the desktop. Not because it's terrible at it but because it needs a few missing pieces that will stop the Year of the Linux desktop from being a running joke.

Strong Core

Linux is admittedly in a very unique position that makes it so different from any other desktop operating system. Aside from BSD, with whom it shares a common heritage, what other operating system would let you choose your user interface and customize it until it breaks? The differences, however, go deeper than UIs.

There's also the choice of distros and, at an even deeper level, package management systems. It's almost more accurate to say "Linux desktops" because of the plurality of combinations.

It's a double-edged sword that is often painted in a negative light. Yes, choice can sometimes be paralyzing and, yes, it might seem that it's a waste of human resources (which is a fallacy of its own). But it also means there is no single point of failure (apart from the Linux kernel itself) and no single entity that will dictate the direction of the operating system, even if it means disenfranchising its own users.

Common ground

It seems that the Linux desktop scene has always been characterized by rivalries. Debian versus Red Hat versus Canonical, KDE versus Gnome versus Xfce, and, now, Flatpak versus Snap versus AppImage. Linux kernel creator Linus Torvalds has been quoted to have given up on the front and look towards Chrome OS and Android for the future of Linux on desktops and mobile.

Being concerned about the kernel only, that might be a pragmatic approach to take, and Torvalds is a pragmatic man. It is, however, a short-term solution to a long-term problem, and a solution that places the fate of Linux desktops and mobiles in the hands of a company who, at some point in the future, could just make its own kernel and drop Linux.

There is some truth to Torvald's criticisms of the current state of the Linux desktop, particularly as it relates to software development and deployment. There are just too many differing distros, package versions, and setups that it makes deploying software properly across even the most popular ones a huge pain in the posterior.

There are emerging technologies like Flatpak and Snap but, as usual, the problem is that these rivaling technologies are backed by rivaling companies and communities. Then there's also the factor that some are just completely against such new systems and would rather stick to the tried and true package managers.

Putting your eggs in the Chromebook and Android basket is one possible solution, but one doesn't exactly need to rally behind a single vendor just to have that unity. For years, the Linux community has developed cross-desktop and cross-distro standards that make interoperability possible.

It might have taken a bit of time but it proved people could agree on a common ground without having to give up their positions too much. It is time to revisit those efforts towards empowering developers of apps and services that people now use on their desktops.

Not a competition

Some people don't think that Linux desktops are worth all that trouble. Sadly, some of those that hold that view are the very ones that have the money and influence to drive Linux development in the direction they want.

These are the big companies like Red Hat and Canonical and SUSE and they probably couldn't care less about Linux desktops as their businesses thrive in the server space – Because that's where the money is.

Linux reigns in servers and supercomputers because Microsoft's easy to use Windows is terrible at such use cases. Apple, on the other hand, cares little about that kind of computing. It's one case where Linux's open source and diverse nature has worked against it.

When you can get the software and support for free, why bother paying for it? Some Linux users do feel that the OS isn't and shouldn't be out to compete and have no problems keeping the status quote.

Survival of computing

It isn't really about competition nor is it just about grabbing more marketshare. It's about making the Linux desktop relevant in an age where computing is slowly moving away from users' control. The face of personal computing is changing, and not just because more people are doing their computing on smartphones and tablets.

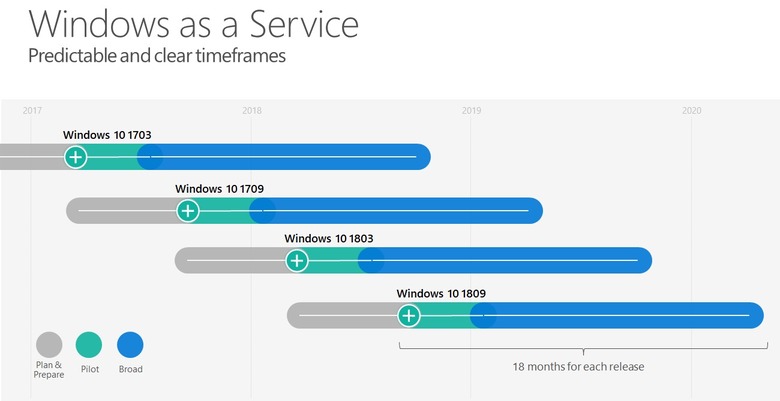

Commercial software is moving towards an "as a Service" model. While that does free up users from having to worry about computing power, requirements, setup, and the like, it also removes much of their control over how they use the software.

Microsoft has pushed Windows as a Service with disastrous results when it comes to updates. Apple seems to be transitioning to becoming a services-oriented company with macOS and iOS as gateways to those subscriptions. Even apps and games are becoming just thin clients for services that run on the cloud.

When the dust of transition settles, Linux might be the only operating system that still values and empowers users rather than treating them as customers only or, worse, products – But not if the Linux desktop space is made nearly obsolete by bickering, NIHS (Not Invented Here Syndrome), and disorganization that will drive away both developers as well as users.

Final Thoughts

There is nothing fundamentally wrong with Linux on the desktop that needs an earth-shattering change, though some may consider its diversity an inherent flaw. It is just fundamentally different from the likes of Windows or even Chrome OS, but that shouldn't be used as an excuse and a crutch not to take Linux to the next level.

Unhindered by vested commercial interests and proprietary technologies, Linux developers, distributions, and companies are in the perfect position to move computing forward and to show the world how computing is and can be done, on servers, supercomputers, desktops, mobile, and, of course, toasters.