Rosetta Hunt For Philae Weighed Against Science Sacrifice

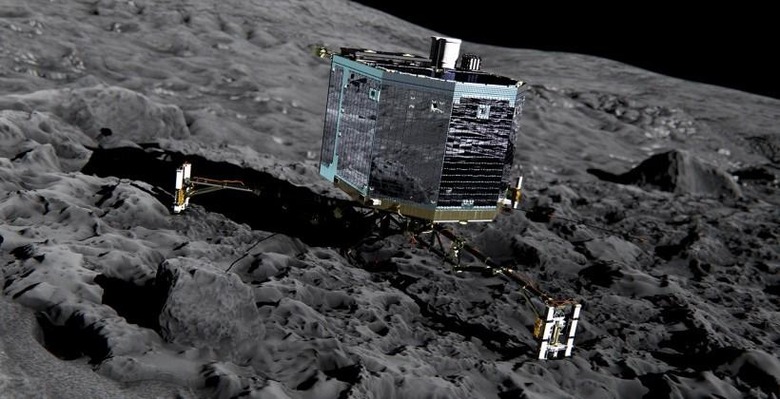

The Rosetta comet probe mission may not have gone entirely to plan, but the science is still pouring out – not to mention water from the comet itself – as the ESA considers hunting down the stalled lander. Triumph at getting the Philae lander to the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko in November 2014 turned to frustration when a less-than-perfect touchdown left the probe short on sunlight and prematurely powered-down. Now, the European Space Agency is considering using the orbiting Rosetta spacecraft to go on a Philae hunt, but there's a price to be paid in potential future research.

The team running Rosetta is considering pushing the spacecraft closer to the comet, Nature reports, so that the high-resolution cameras onboard could hopefully snatch a shot of where Philae came to rest.

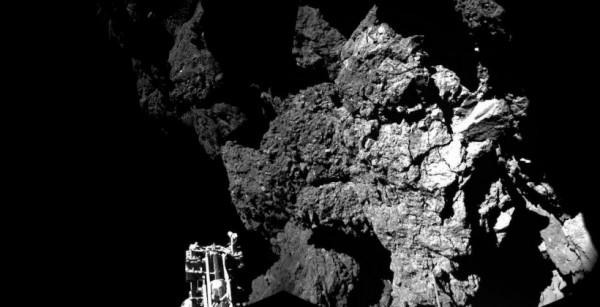

Originally, the plan had been to land Philae in an open space on the comet, giving it room to unfurl its solar panels. Instead, the probe bounced up from its initial touchdown and drifted, finally settling in a still-unknown location on the hurtling space rock.

More pressing than the mystery position was the fact that it received far less sunlight than the ESA had counted on, and once the batteries onboard – only intended to suffice for the initial landing – were depleted, Philae shut down.

Now, the ESA is considering a low-level fly-by, taking Rosetta down to just 6km (3.7 miles) above the surface of the comet and going exploring in the roughly 20 x 200 meter plot the lander is believed to be located in. It's a plan with inherent drawbacks, however, not least the quantity of fuel that would be burned in the process.

As a result the ESA would have to cross some of its planned research projects off the to-do list, including an existing scheduled fly-by that would produce new images of 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko in unprecedented detail.

That science compromise could be costly, as Rosetta's mission is already producing some impressive results. For instance, NASA reports, the spacecraft has identified water "pouring" out of the 2.5 mile wide comet using the Microwave Instrument for Rosetta Orbiter, with a tenfold increase in the amount over the three months ending August 2014.

"To be up close and personal with a comet for an extended period of time has provided us with an unprecedented opportunity to see how comets transform from cold, icy bodies to active objects spewing out gas and dust as they get closer to the sun," NASA's Sam Gulkis said of the findings.

Other research has identified that the comet's atmosphere is far less homogenous than NASA had expected, not to mention that its outgassing varies significantly over time. "These results are helping us move the field forward on how comets operate on a fundamental level," Claudia Alexander, NASA project scientist for the US Rosetta team, said.

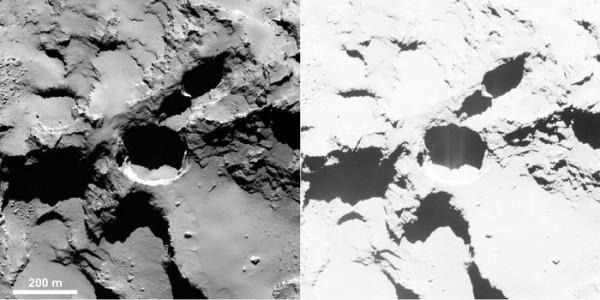

The ESA, too, has been sharing some of its own discoveries from Rosetta, including identifying five types of terrain including "active pit" areas. These funnel gases up into space, when ice is heated and turns gaseous before rushing up through the necks and pits that pepper the comet's surface.

If an unscheduled hunt gets the go-ahead, Rosetta will need some time to change the flight plan, which is organized months in advance. The ESA expects to reach a decision before the week is through.