Pumpkin Toadlets Bones Revealed To Glow In Patterns

Two species of tiny pumpkin toadlets were the subject of a research project published today, them and their glowing bones. This isn't the first time these little babies (Brachycephalus ephippium and B. pitanga) were discovered – they've been known since the year 1824 when they were first classified by the German biologist Johann Baptist von Spix. Today we got some insight into the reasons for this endangered species' strangest feature – internal florescence!

I know what you're thinking. Man, it's so cool when animals have bioluminescence and can glow in the dark – right? That's not exactly what's going on here. With the two species of Brachycephalus we've learned about today, the light comes only when they're shined upon with ultraviolet light.

The last time these hoppers hit headlines, it was due to their deafness. They apparently cannot hear themselves make their own chirps. Both the male and the female are deaf to the call. Instead, it's the physical action in making the call – the swelling of the throat of the male – that attracts the female. Hence, evolution.

That study was conducted by Sandra Goutte and a team of researchers. This newest bit of research is by Sandra Goutte and crew, too. Goutte and crew spoke about the fact that some chameleons have also been known to show bone fluorescence, also due to thin layers of skin.

In fact all bones have some level of fluorescence – it's just that most bones can't be seen from outside the skin of the creature in question.

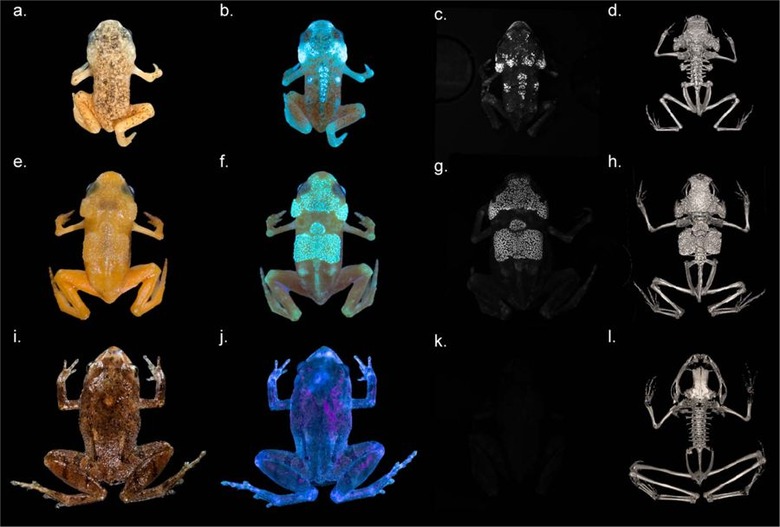

Bones emit florescence at their most intense when illuminated with 365–385 nm (UVA) light. The reason we're able to see the fluorescence isn't just that these bones are special – it's because the toadlets' skins are extremely thin.

The study points also toward previous research which found that the skin of South American treefrogs Boana punctata and B. atlantica (Hylidae) were fluorescent, too. Instead of emitting from the bones, these treefrogs glowed (and still glow) from their external skin, and not in any sort of discernible pattern. They're also fluorescent under 390–430 nm (purple-dark blue) light, while the toadlets' glow is strongest under UVA.

These toadlets don't show much of any glow in their youngest states. That's before the dermal ossification develops. You'll see some of this action going on in the photos above and/or below – Photographs taken by S.G. and C.J..

In the conclusion of the study, researchers suggest that "the functions of these fluorescent patterns remain speculative." Goutte and crew go on to note that "thorough in situ light spectra measurements and behavioral studies are needed in order to determine whether conspecifics and/or potential predators respond to fluorescent patterns in Brachycephalus toadlets, and in what way."

They've still got a whole lot more to learn! Biochemical and in in use – we've got more to get into! For now, if you'd like to learn more, head over to the research paper "Intense bone fluorescence reveals hidden patterns in pumpkin toadlets." That's authored by Sandra Goutte, Matthew J. Mason, Marta M. Antoniazzi, Carlos Jared, Didier Merle, Lilian Cazes, Luís Felipe Toledo, Hanane el-Hafci, Stéphane Pallu, Hugues Portier, Stefan Schramm, Pierre Gueriau, and Mathieu Thoury, and was published by Scientific Reportsvolume 9, Article number: 5388 (2019).