New Microbatteries Can Jump-Start Your Car Battery And Still Charge Your Phone

The researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign have developed new microbatteries that are extremely small in size, but pack a huge amount of power. Not only do they pack a huge punch, but they recharge "1,000 times faster than competing technologies", according to the research team. The team wanted to find a solution to the dilemma that afflicts current power sources, where power sources can either have a lot of power, or have a lot of energy, not both at the same time.

William P. King, Bliss Professor of mechanical science and engineering at the University of Illinois, and the leader of the research team, says,

"If you want high energy you can't get high power, if you want high power its very difficult to get high energy. But for very interesting applications, especially modern applications, you really need both. That's what our batteries are starting to do. We're really pushing into an area in the energy storage design space that is not currently available with technologies today."

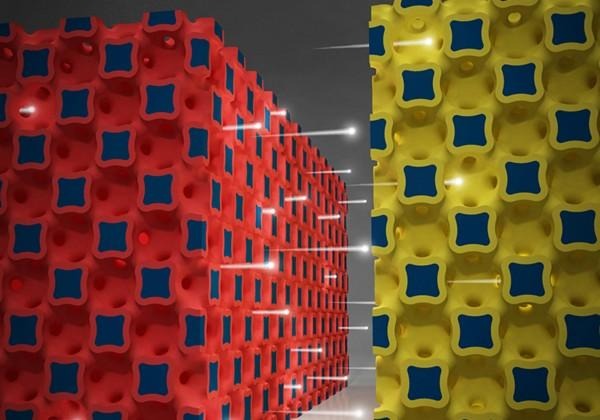

The microbatteries feature an internal three-dimensional microstructure. Batteries have two main components: the plus side (cathode) and the minus side (anode). Using the fast-charging cathode design developed by Professor Paul Braun and his research group, King's group developed a matching anode design and integrated the two together at the microscale to create microbatteries with extreme performance. The batteries are so powerful, they can recharge 1,000x faster than other batteries, broadcast radio signals 30x farther, and drive innovations for devices that are 30x smaller.

The new batteries are said to "out-power the best supercapacitors" and would drive new innovation in technology. The team believes that a cell phone powered by these microbatteries would be able to jump-start a dead car battery, and still have enough energy to recharge a phone "in the blink of an eye". The research team is now planning on integrating these microbatteries with other devices, and are also trying to figure out a way to manufacture these at a low cost. Liz Ahlberg, Physical Sciences Editor for the University of Illinois, says,

"Imagine juicing up a credit-card-thin phone in less than a second. In addition to consumer electronics, medical devices, lasers, sensors, and other applications could see leaps forward in technology with such power sources available."

[via University of Illinois]