Closest-Ever Images Of The Sun Released - And They Expose A New Mystery

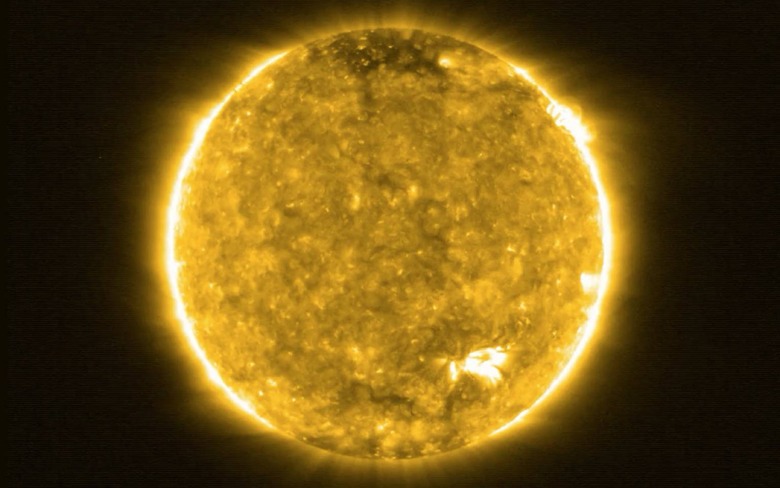

NASA and the ESA have released the closest pictures ever taken of the Sun, jaw-dropping new photos captured by the Solar Orbiter as it came within 48 million miles of our closest star. A collaboration between the US and European space agencies, the spacecraft is designed to bring back information from deeper in the heart of the solar system than any probe before it, in the hopes of unlocking some of the secrets of the Sun.

While it may look like a fairly consistent orange ball from Earth, the reality is that the Sun is constantly in flux. Changes in roiling solar flares and electromagnetic radiation can have significant impact on Earth, across things like weather patterns and how electronics operate.

Trying to figure out what happens, exactly, and whether we can better predict the Sun's behaviors in future was a key goal of the Solar Orbiter mission. Launched on February 10, 2020, the mission is expected to last at least seven years. However it only made its first close solar pass on June 15.

That saw it come within 48 million miles of the Sun, and all ten of its various instruments power up to gather data. They track the star's activity across a variety of different measures, though NASA says it wasn't really expecting anything groundbreaking for this first pass beyond confirmation that everything was operating as intended. That meant the findings from one of the instruments came as a surprise.

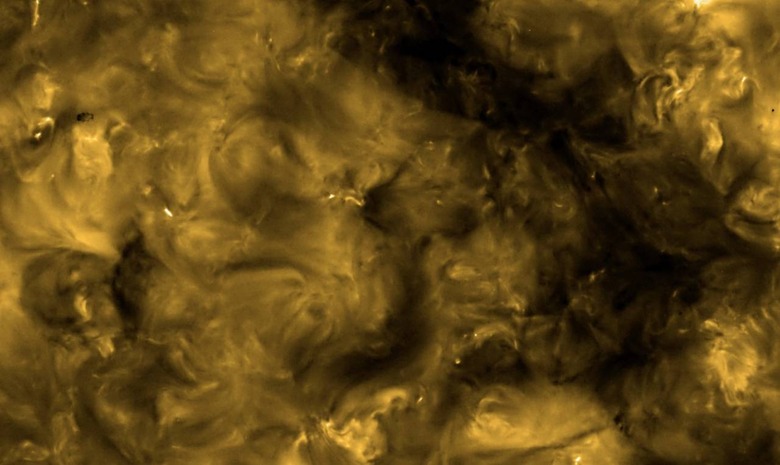

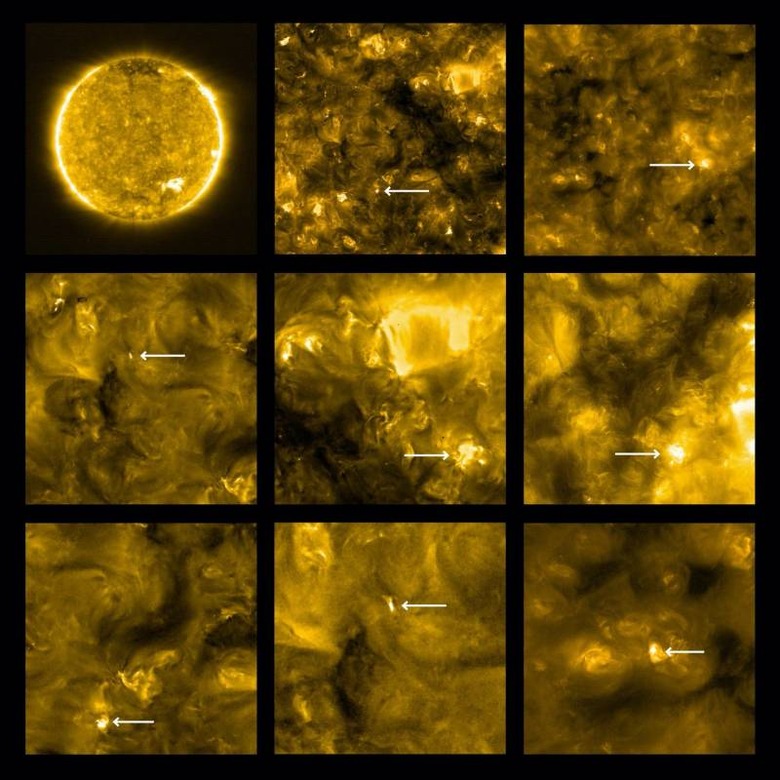

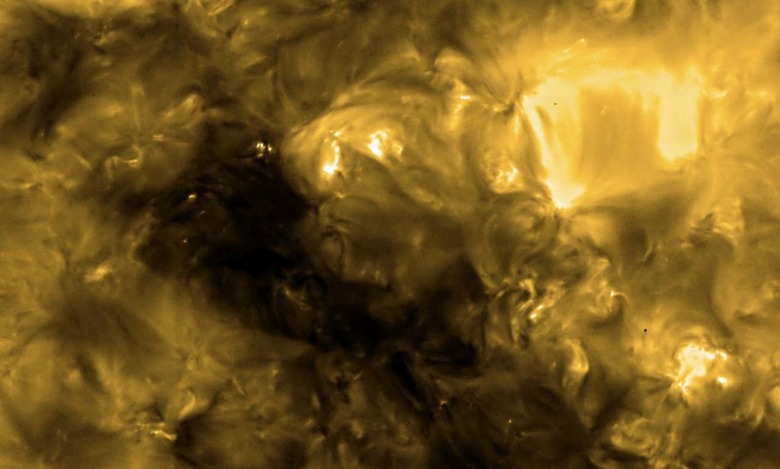

The Extreme Ultraviolet Imager, or EUI, found what are being referred to as "campfires" dotted all over the Sun. Considerably smaller than the known solar flares, by a factor of anything up to a billion, they're "the little nephews" according to principle investigator David Berghmans, an astrophysicist from the Royal Observatory of Belgium.

It's not what was expected to be found, and so far scientists aren't sure what the "campfires" actually are. According to NASA, "it's possible they are mini-explosions known as nanoflares – tiny but ubiquitous sparks theorized to help heat the Sun's outer atmosphere, or corona, to its temperature 300 times hotter than the solar surface."

The next step will require a new pass, and the Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment instrument. It should be able to provide a more precise measurement of just what temperature each campfire reaches.

While it's just the start of the Solar Orbiter's work – and the work of scientists back on Earth, sifting through the raw data the spacecraft's instruments generate – it's already shaping up to be more of a success than perhaps could've been hoped. When future passes take the probe closer to the Sun, we'll get more information about things like the magnetic field of the star, its solar wind structures, and more.