MIT Researchers Think Life May Thrive On Hydrogen Planets

Sara Seager, the Class of 1941 Professor of Planetary Science, Physics, and Aeronautics and Astronautics at MIT, wants to avoid a situation where humans might encounter alien organisms but fail to recognize it as actual life. Seager wants to cast a wider net when looking for environments beyond our own that might be habitable. Seager and fellow researchers recently published a paper noting observations and laboratory studies that show microbes can survive and thrive in atmospheres that are dominated by hydrogen.

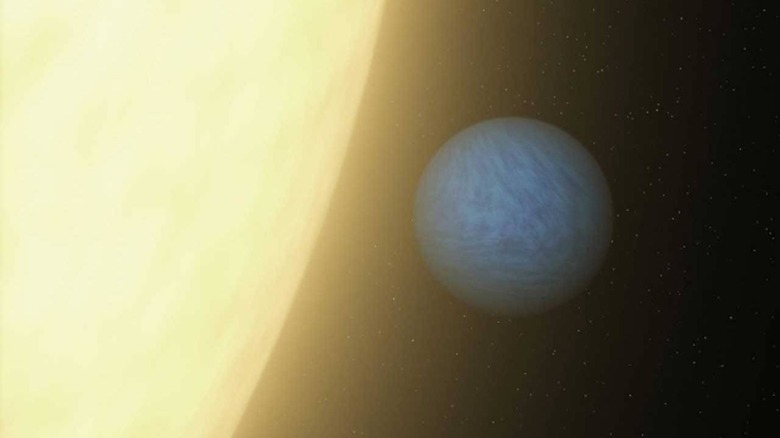

An atmosphere dominated by hydrogen is vastly different from the atmosphere on Earth composed mainly of nitrogen and oxygen. The researchers say that since hydrogen is a lighter gas than nitrogen and oxygen, an atmosphere that's rich with hydrogen would extend much further out from a rocky planet. With an atmosphere that extends further out from the planet, the team says it would be easier to observe and study by telescopes compared to planets with a more Earth-like atmosphere.

The research performed by Seager shows that the simplest form of life could survive on planets with hydrogen-rich atmospheres. The research shows that astronomers should consider using next-generation telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope to search hydrogen-dominated planets for signs of life. She says that there is a diversity of habitable worlds out there and that it is confirmed Earth-based life can survive in a hydrogen-rich atmosphere.

Seager says that "we should definitely add those kinds of planets to the menu of options when thinking of life on other worlds, and actually trying to find it." In the research, the team studied the viability of two types of microbes in an environment consisting of 100% hydrogen. The organisms were the bacteria Escherichia coli and yeast. Neither had been previously studied in hydrogen environments.

The team found that both could survive with or without oxygen. Researchers found that they were able to prepare their experiments with either organism and open-air for transferring them into a hydrogen-rich environment. The team found that in an environment of 100% hydrogen, the live microbes represented a classic growth curve. Seager is clear that the experiment conducted wasn't intended to determine if microbes could depend on hydrogen as an energy source.