LOOPER time travel gets real in SlashGear's chat with Dr Edward Farhi

It's almost time for the big drop of the new science fiction action time travel blockbuster LOOPER to hit theaters, so SlashGear took the opportunity to speak with none other than Dr. Edward Farhi of real-life time travel study fame. What we learn from Farhi, aka Director at the Center for Theoretical Physics at MIT, is that time travel into the future is indeed very possible – theoretically – but that backwards movement – like LOOPER suggests – just isn't in the cards.

Farhi and colleagues Sean M. Carroll and Alan H. Guth worked on a report by the name of "An obstacle to building a time machine" which lets it be known that the amount of mass that would have to be destroyed to make a time machine work would essentially break apart half the universe. That's a time machine that travels along closed timelike curves – what we're interested in is a machine that jams a single human back in a metal tube from 30 years in the future to our own present – or in the case of the LOOPER plotline, just a few decades into the future (and 30 years from then.)

UPDATE: Check our full LOOPER movie review now!

Dr. Edward Farhi : There are two forms of relativity – one's the Special Theory of Relativity [STR] and the other is the General Theory of Relativity. Relativity tells us that the rate at which clocks run depends on the speed of the system. And when we talk about clocks, we're talking about the actual flow of time. It's not something that just feels like it's going at a different rate, it's actually going at a different rate.

One thing we know is that if you could get into a rocket in space and go close to the speed of light and return to Earth, you could arrange it so that a short period of time elapsed according to you would be a much longer period of time elapsed on the Earth. For example I could put you, Chris, on a rocket, and you would say that 6 months have passed and you'd come back to Earth and 100 years have passed on the Earth – if you had kids, you would meet your great great grandchildren.

We call that "skipping into the future."

Farhi : It's actually allowed by the laws of physics. That rate at which you're clock runs depends on the speed – another example is the GPS satellite. When you're in your car you communicate with these satellites that triangulate your location. It's very important that you understand that the rate at which the clocks run on those satellites is important – if you didn't take into account the fact that the clocks are running at a little different rate because they were moving, you'd be driving in the ditch.

Moving clocks run at different rates, and that allows you to skip into the future.

The other thing is that if you've got a strong gravitational field it'll also affect the way clocks run. So if I took you and I lowered you into a strong gravitational field, your clock would run slower. And if you were watching out, if you were watching me on the Earth, you would see me moving quickly and I would see you moving slowly and when we came back together again, you would have aged less than I. Those are real effects, there's no doubt about these things.

Farhi : If you took that little trip and you went into the future and you wanted to come back, that would be a little more problematic. One of the reasons we can see it would be a little more problematic is that if you could go into the future and come back, then maybe you could today just go back – and if you could go back in time, you could prevent your parents from coming together and making you. That's paradoxical. Most physicists, I would say, because of those paradoxes, going back in time doesn't seem too possible.

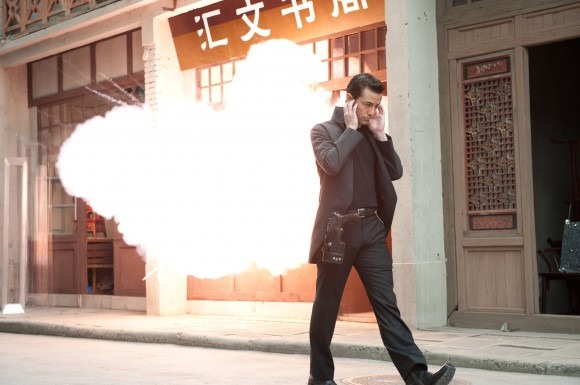

Check out our LOOPER review tonight and see the full film out in theaters this weekend across the USA! This is a film that's made for those who love loud blasts, massive kills, and massive amounts of mystery. It's an investigative adventure from start to finish, one you'll not want to miss on the big screen – and specifically there too, it's a real experience.