If Not For This Near-Extinction Mystery The Oceans Would Be Full Of Sharks

Were it not for a mysterious near mass-extinction event roughly 19 million years ago, the oceans could be filled with a whole lot more sharks than they are today. Those prone to galeophobica should probably look away, because a new study of deep sea shark tooth remains suggest populations could've been exponentially higher had the marine predators not faced a dinosaur-style wipeout.

The event took place in the early Micene era, according to new research by scientists at Yale University and the College of the Atlantic. They sifted through shark teeth and scales at the bottom of the oceans, which had been preserved in deep-sea sediments: unexpectedly, there were signs of a huge drop in shark abundance.

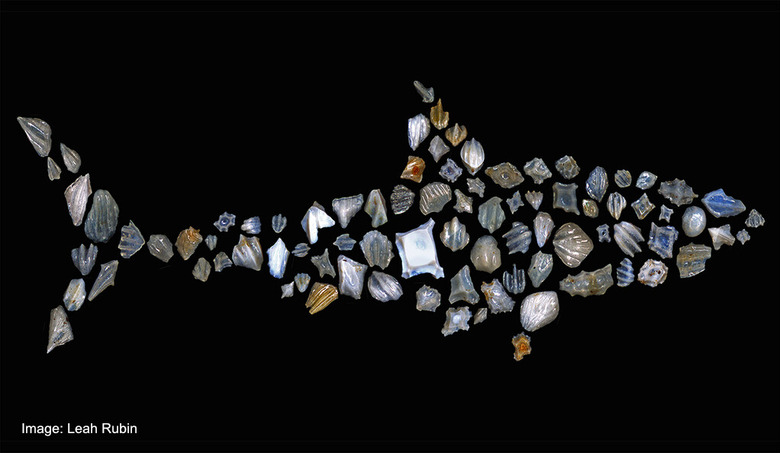

More than 70-percent of the world's sharks died off, researchers Elizabeth Sibert and Leah Rubin calculate. While dramatic in its own right, it's all the more astonishing given the relative impact the mass extinction event which killed off the dinosaurs 66 million years ago had on shark populations. That only had half the hit, in comparison.

While scientists believe they have a pretty solid understanding of just what happened to the dinosaurs – and, indeed, destroyed about three-quarters of the animal and plant species on Earth – adding to the shark strangeness is the absence of a similar event on the calendar in the Micene period. "This interval isn't known for any major changes in Earth's history," Sibert explains, "yet it completely transformed the nature of what it means to be a predator living in the open ocean."

Clearly, sharks persisted, and are still a feature of modern oceans. However there could be significant differences between those ancient sharks and what we know of the species today. "Modern shark forms began to diversify within 2 to 5 million years after the extinction," the researchers say, "but they represent only a minor sliver of what sharks once were."

The long-ago impact wasn't equally spread. Shark deaths in the open ocean were higher than for coastal waters, leading to suggestions that current shark preferences for those areas may in part link back to that mystery event.

Though nowhere near the same extent, shark populations have declined in recent years for human-led reasons. The concern now is that what's assumed to be a fearsome predator of the oceans may in fact be more precarious than previously considered. After all, with shark diversity taking a huge hit, there's less resilience in the overall species as a result.