Going 'Catatonic' In VR's Horror Underbelly

It's no secret that I love horror movies, the reasons for which are both numerous and irrelevant. I've seen hundreds of movies in the genre over the years, most of them cheesy with healthy half and one-star ratings on Netflix. It's not that I like crappy movies; rather, the genre suffers from one big problem: true fear is very hard to impart through traditional film. That's where virtual reality comes in.

When it comes to horror, these movies are usually split into two categories: gore and non-gore. Gore movies are easy — you gross out an audience for 90 minutes and call it a day. People aren't so much terrified as they are nauseous and very uncomfortable. It's easy to gross someone out. Truly scaring viewers, though, is more difficult. Horror fans have long been disappointed by the endless empty promises of supernatural and otherwise non-gore movies promising to finally, truly, literally scare you at the visceral level.

I'm looking at you, Paranormal Activity.

I can't remember the last time a horror movie scared me. If I watch enough of them in the right setting they'll put me on edge, sure. But scared? No. Jump scares lost their effect years ago. Dramatic music and prolonged high-tension scenes can only take a viewer so far. A couple hundred horror movies later and they're all like a special comedy niche that happens to include a lot dismemberment.

Ask any horror lover why horror movies often suck and you'll get a bunch of different theories. Many people agree, though, that fear is a special kind of emotion. It's very personal, very isolated. Often, being scared is more about the implications of something rather than the thing itself. Fear is caused by a real or perceived threat to your survival; it exists to compel you to get away from something that might hurt or kill you.

That doesn't translate well on the big screen because movies largely depend on viewers being able to suspend their sense of disbelief. To be truly afraid while watching a horror movie, you'd have to suspend your sense of disbelief enough to accept that maybe, just maybe, that serial killer is in the room with you, that shadow is right behind you, that sinkhole just opened under you. Your brain would have to be convinced what you're witnessing is really happening to you and that you just might die from it.

It's easy to see why virtual reality holds so much promise for the future of horror entertainment. The whole point of VR content, after all, is to experience a different world as if it is your own.

This past weekend, I decided to see if VR horror content could scare me. Not put me on edge or creep me out, but scare me.

The Setting

My setup was pretty simple: I used Google Cardboard with a Galaxy S6, as I'm still waiting for my Gear VR to ship. I locked myself in a room with orders for no one to disturb me. Masking tape was used to seal the Cardboard headset to keep light from leaking, and a swivel chair was used for maximum mobility. Bluetooth noise-isolating earbuds rounded out the trappings.

11:57

My first experience was with 11:57, a short interactive horror film where you can look around within a video while it plays.

I'd psyched myself out so much over the thought of a jump scare happening with the display strapped to my face that I was on edge before even starting the film. It only lasts a few minutes, and while I won't ruin it for you, it's not scary. Neat, but not scary. I was disappointed by the end, but had also managed to shed the jitters by this point, hopefully leading to a more pure experience with the other apps.

Insidious 3 -- A 3D Trailer

This app is an interactive trailer for the movie Insidious 3, a horror flick. It hints at the future of trailers — rather than passively watching them, you can strap on a VR headset and take part inside of them. For that reason I found the app interesting, but still the verdict is not scary. To be fair, though, I'd already watched the movie.

VR Horror Games

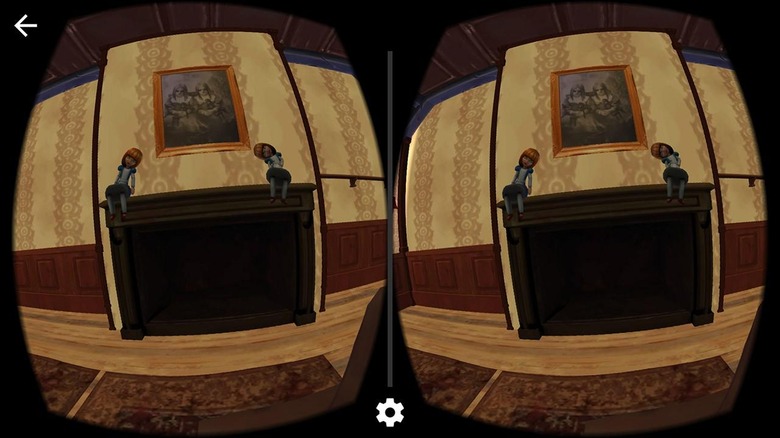

Maybe a game is what I needed, I reasoned. After all, the two other apps were very short lived, and in my estimation it takes about three minutes before my brain starts to accept the virtual reality as being legitimate. I tried a bunch of VR horror games: Sinister Edge, Halls of Fear, Sisters, Silent Home: Horror House, Chair in a Room, and more.

Unfortunately, none of these games are scary — more often than not, they're frustrating, which is the case with many VR apps. They're just not up to par yet; bugs and drifting, poor graphics, and cheesy audio are common issues among most of these titles, and it's hard to get sucked into something that crashes or looks like an N64 game.

Catatonic

Bummed by the lack of substantial content, I happened across the evening's most exciting news: Catatonic, a five-minute trip through an insane asylum, was finally finished. I'd waited so long for it to be completed that I'd stopped checking months ago. The video is available through VRSE, an app that itself can be downloaded from the Google Play Store. Catatonic is a little over 500MB, but the higher quality helps the experience immensely.

For those unfamiliar, Catatonic is about five minutes long, and takes place in an insane asylum with you as the patient. When the video blinks to life, you're a patient in a wheelchair in an enclosed elevator, an orderly behind and a green hospital smock covering your legs. They'll be some minor spoilers henceforth, so go watch it yourself first before continuing.

After watching 11:57, I wasn't expecting much from this app, and for the first couple minutes I found it just as boring. While the setting was creepy enough, it was just a lot of passive observations of stereotypical horror tropes: a crazy person behind a glass door, a growling girl shackled to a box, creepy nurses doing vaguely creepy things. The orderly would slow down or stop at some points, giving you a few extra seconds to look around.

Things start to get interesting, though, when you end up in the basement and meet the doctor. The scene, were it part of a regular horror movie, would have been eye-rolling. But experienced through VR, with this doctor getting right up in your face, it was quite unsettling. After he moved in close the second time, I caught myself moving to shove him away. It didn't help that my brain was starting to perceive the VR world as real at this point.

It got worse from there, though, with other people joining him the room: fever dreams or ghosts or real crazy people visible during moments of lucidity — it didn't really matter, because I was surrounded by them and it was intensely uncomfortable. As one moved out of my line of sight, I caught myself flinching as my brain was trying to make sense of the empty space around me; part of me knew it was just my empty bedroom, but another part was freaking out, feeling certain one of those beings were going to latch onto my shoulder.

The experience was difficult to describe; though I knew it wasn't real, the dynamic eventually shifted so that rather than trying to convince myself it was, I had to start reminding myself that it wasn't. That didn't matter, though, when some extra-tall lanky being in what is best described as a BDSM mask got right down in my face, closer and closer until reminding myself it wasn't real was fruitless. I ripped the headset off my face. That scene — one that would have been dismissed in an ordinary movie — scared the bejesus out of me.

This is just beginning

Catatonic reached its end shortly after the scene above, and though I was immensely satisfied with the experience, it best served to highlight the things still wrong with VR and how grand the future of content will be once they're ironed out.

Low resolution imagery was the biggest problem, which was the fault of the setup I was using. Had Catatonic been in razor sharp UHD/60fps, for example, I'm sure the experience would have been far more uncomfortable much sooner. The lack of adequate sensory data is another problem — at one point the doctor is inserting a needle into your hand, for example, but that does nothing for the viewer because there's no sensory data to go with it. You're instantly relegated back to the position of passive viewer, and it's boring. Prototypes of gloves that track finger movement and provide sensations will one day solve that problem, but that day won't arrive for more than a year in all likelihood.

And, of course, the content itself is still in its infancy, with creators figuring out the best way to leverage the technology and how to restructure the way stories are presented. We're a long way off from a high-quality feature length fully immersive virtual reality horror movie, but there's no doubt it is coming and when it does, the horror entertainment genre will never be the same.