First coronavirus vaccine trial has a long road ahead

Coronavirus vaccine trials may have begun – and several possible treatments show promise – but it looks likely to be a long time before any new COVID-19 medications are ready for widespread deployment. The first Phase 1 clinical trial for a COVID-19 vaccine began earlier this week in Seattle, exploring how 45 different volunteers react to an experimental vaccination. However it's not a fast-track to public treatment.

The vaccine itself is the handiwork of Moderna, a pharmaceutical company based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It's designed to prompt the body's cells to express a virus protein; that, so the idea goes, would hopefully encourage an immune response. If the treated individual comes into contact with coronavirus later on, the body would already have the immunity to deal with it.

That's the theory, at least. Clinical testing is needed to figure out whether the vaccine – called mRNA-1272 – is as effective on people as it seems to be in animal models. Usually those trials can be several years or more in length, but the goal is to fast-track a coronavirus so that it can be deployed more rapidly.

Even then, it won't be a quick process. The 45 volunteers in Seattle will first be screened, then have two vaccination sessions, and finally eight follow-up visits. The injections of mRNA-1273 will be administered in the upper arm, 28 days apart. The group will be split into three cohorts, getting three different amounts in their injections: 25 micrograms (mcg), 100 mcg, or 250 mcg.

In total, the study is expected to run for 14 months, and is funded by the US National Institutes of Health. That's in line with predictions elsewhere that an effective vaccine could still be 18 months away from realization. Recent reports have indicated that, if COVID-19 is to be managed during that period and mass deaths avoided, suppression and mitigation efforts will need to continue pretty much uninterrupted until then. The good news is that initial data could be available from the trial as soon as three months in, though it's unclear what value that will have at this stage.

Three coronavirus vaccines have promise

mRNA-1273 isn't the only potential vaccination that could turn the tide of COVID-19 infections. As well as Moderna, two other pharma firms – BioNTech and CureVac – are also looking into mRNA therapies.

mRNA, or messenger RNA, is a type of single-stranded ribonucleic acid, one of the nucleic acids present in all living cells. RNA is used as a messenger for DNA, controlling and regulating how proteins are constructed. In the case of mRNA specifically, it's designed to tell the cell how to make the protein found in the COVID-19 virus.

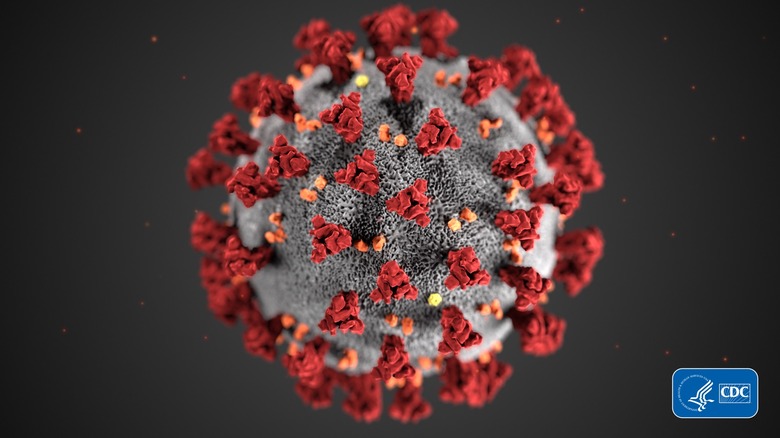

The vaccine isn't made from coronavirus itself, and nor can it cause infection. Instead it's designed to help the body teach itself how to break down the "spikes" on the COVID-19 sphere, which the virus uses to bind to human cells. mRNA-1273 is a derivative of another vaccine work-in-progress which Moderna was developing for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS).

Both BioNTech and CureVac and also exploring the use of mRNA as a route to coronavirus immunity. Development of each is underway, and clinical trials could kick off later this year. Again, though, there'll be some time before the results indicate widespread treatment is recommended, if indeed the vaccinations prove to be effective at all.