Cancer-Targeting Treatment "Steps On The Gas" To Kill Tumors

Many have heard of immunosuppressive drugs, which are a type of medication that suppresses the immune system, but lesser-known are immunostimulatory drugs, which stimulate the body's immune system. The latter is a potential solution for treating cancerous tumors, as the drugs trigger the immune system to attack the mutated cells. The problem? Ordinarily, such drugs could also cause the immune system to become overstimulated, attacking healthy cells with serious — sometimes deadly — consequences.

That's a problem the MIT researchers behind a new cancer immunotherapy study have addressed. Whereas introducing an immunostimulatory drug into the entire body can cause the immune system to attack healthy cells, the new delivery method detailed in Nature Biomedical Engineering is designed to target cancerous tumors specifically.

The method involves introducing IL-12, a type of stimulatory molecule, directly where the tumor is located — the team refers to this as "stepping on the gas." That aspect of the wider immunotherapy treatment is joined by another process the researchers describe as "taking off the brakes," at least when it comes to cancerous tumors and the way in which they fight back against the immune system.

While a healthy immune system is typically very effective at clearing out old, damaged cells and fighting against infections, cancerous cells — which have mutated genes — produce their own molecules that suppress the immune system's ability to attack them. This reduces the body's ability to fight against and remove cancer cells, allowing them to grow and, eventually, spread into other parts of the body.

The researchers note that while this issue can be addressed using existing drugs called checkpoint blockade inhibitors, the pharmaceuticals only work on certain types of cancer. Combining these inhibitors with immunostimulatory drugs, however, may be more effective against resistant cancers, giving immune cells the boost they need to attack the tumors.

All of this circles back around to the problem of unwanted side effects that come with stimulating the immune system, including things as severe as organ failure, according to the researchers. That's where their work comes in — it revolves around targeting the stimulatory molecules directly at the tumors, essentially letting the body know to only attack those cancerous cells while leaving the other healthy cells alone.

Work on the project has been underway for years, including a previous study from the team published in 2019 (via MIT) that involved targeting IL-12 molecules at cancerous tumors in mice. This new study evaluates an improved way to bind the IL-12 molecules and cytokines (immune cells) to tumors, swapping out the previously used collagen-binding protein with a compound called aluminum hydroxide (alum).

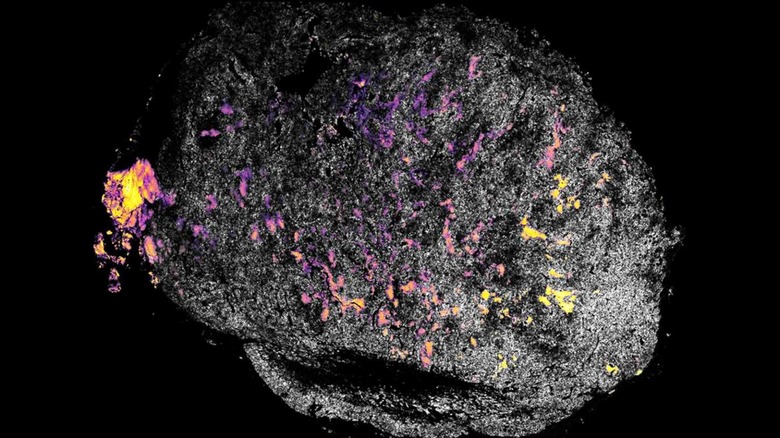

Alum particles are so small they're measured in microns, the researchers explain, noting that the small sizes mean the particles will remain where they were injected for up to multiple months. The study involved testing this potential immunotherapy treatment in mice, which were treated with a checkpoint blockade inhibitor and injected with IL-12. The results were promising.

The mice used for the study were inflicted with three different types of cancers; the treatment's success in eliminating these tumors ranged from 50- to 90-percent. Of note, some of the mice had been injected with breast cancer cells that later spread into the lungs.

The IL-12 treatment was found to eliminate the tumors that had spread into the lungs even though the injection was only given at the original tumor site. The results were less astounding when the injection was given without inhibitors, though the researchers say the IL-12 with alum alone "showed some ability" to trigger the immune system against cancer cells.

As if that isn't exciting enough, the researchers say the mice treated with this immunotherapy method didn't experience any of the side effects that occur when IL-12 is introduced into the body without any way to specifically target tumors. What does that mean for human patients?

The inhibitor drug used as part of this treatment is already FDA approved, according to the researchers, and a startup has already licensed the tech. That startup, MIT notes, will conduct its own alum-IL-12 study and, should it also find favorable outcomes, it'll move on to additional testing that combines the immunostimulant and inhibitors.

It'll still be a while before such immunotherapy treatments become a common way to treat cancer and certain other diseases, but this work represents a huge step toward that future.