Antarctic Methane Is Leaking And The Climate Change Impact Could Be Huge

A new source of methane leaking into the Antarctic ocean has been discovered, with concern about how the greenhouse gas could be driving climate change. Although so-called methane seeps – where the gas bubbles out from an underground reservoir and into the ocean – have been identified in multiple locations around the world, this latest example is the first to have been spotted in Antarctica.

It's the handiwork of a team of marine ecologists from Oregon State University, and the subject of a study published today in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B. While this may not be the first methane seep identified, the researchers believe it to be "fundamentally different" to others.

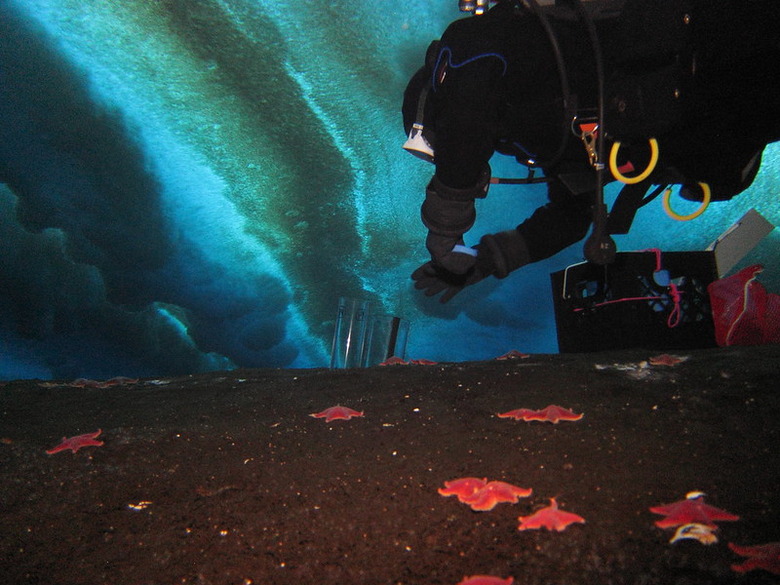

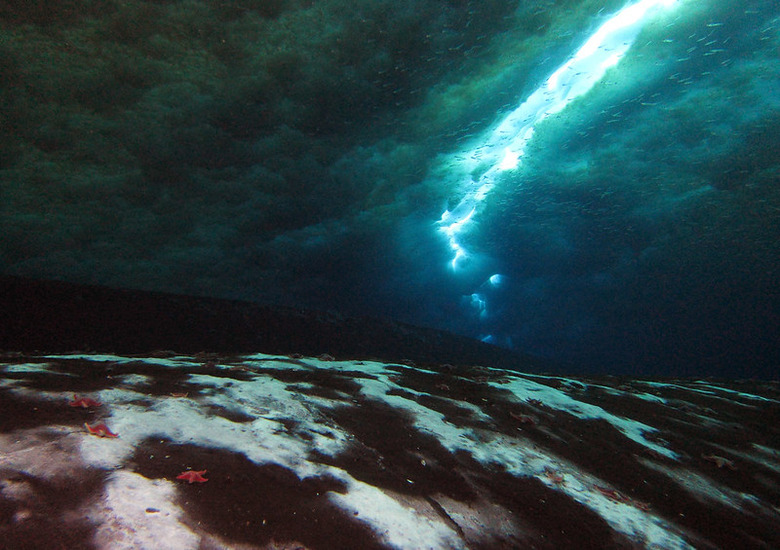

Typically, methane seeps would be accompanied by a microbial mat: a layer of bacteria which live on the microbes that feed on methane. While this Antarctic seep does have a microbial mat – indeed, it's around 230 feet long and 3 feet in width – roughly 32 feet beneath the frozen surface of the ocean, it's not been behaving as others might. Developing later than previous models would have predicted, the microbes in the mat aren't consuming all the methane, either.

That means it's likely that at least some of the gas is escaping into the atmosphere, the researchers suggest. Given how potent a contributor to atmospheric warming methane is, that's a worrying discovery.

"Methane is the second-most effective gas at warming our atmosphere and the Antarctic has vast reservoirs that are likely to open up as ice sheets retreat due to climate change," Andrew Thurber, one of the authors on the study, explains. "This is a significant discovery that can help fill a large hole in our understanding of the methane cycle."

In the course of five years of studying the seep, and the way the microbial mat formed, assumptions about how rapid those microbes colonize the area were challenged. The most common sort of methane-consuming microbes didn't appear until after five years after the seep formed in 2011, for example. Scientists had previously believed that it would be a far quicker process.

"What was really interesting and exciting was that the microbial community did not develop as we would have predicted based on other methane seeps we have studied around the globe," study co-author Sarah Seabrook explains.

The hope is that, through further examination of the methane seep and the ecosystem forming around it, the team can figure out whether this atypical development is something pretty much exclusive to the Antarctic regions, or in fact a sign of how all seeps are early on in their lifespan.

Lending weight to the concern is the sheer quantity of methane that's believed to be trapped under Antarctica. The region is believed to contain a quarter of Earth's marine methane, in fact, and until now it was unclear just how much, if any, was escaping into the planet's atmosphere.