Android Distribution In 2016: Updates Are Still A Mess

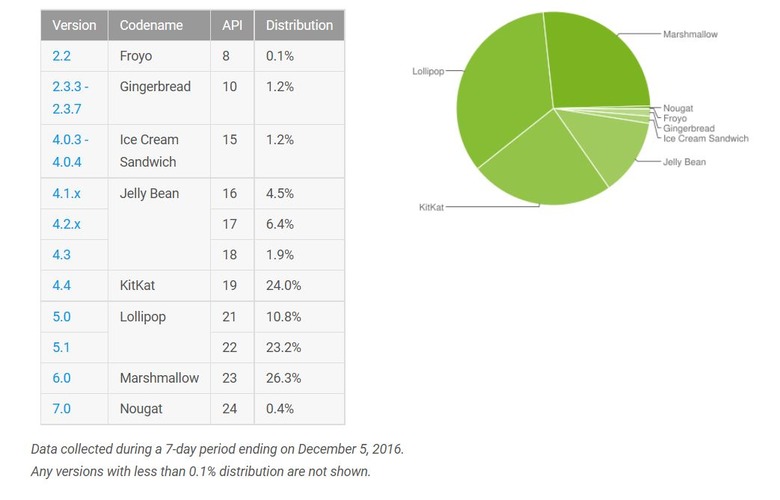

Google has just updated its Android developer dashboard, the last time it will do so before the year ends, and the numbers are in. Android 5.0 and 5.1 Lollipop, not 6.0 Marshmallow, has the largest piece of the pie. Android 7.0 Nougat, which was released to the public back in August, is only installed on 0.4% of the devices in the market, mostly Nexus and some third-party ROMs. While it might seem good, at a glance, that devices and OEMS are converging on just two to three versions nowadays, the numbers show one undeniable fact. Eight years into its existence, Google and its partners still can't get updates right.

A smidgen of history

Let's take a look at just the most recent versions of Android. 4.4 KitKat was released on October 2013 but it never even got to 50% of devices in the market. Android 5.0 Lollipop launched in November 2014, followed by 5.1 not long afterwards in March the following year. Even combined, the two have yet to go past 40%. Marshmallow (6.0) went gold in November 2015. A year later, it just passed one-fourth of the devices in the market. Android 7.0 and 7.1.1 Nougat is off to a very slow start, entering the charts only last November and hasn't even reached 1%.

There is a clear pattern here. Adoption of new Android versions may be strong, but things really only come to a head more than a year after that version was launched. By that time, however, a new major Android version has been released, which will eventually eat away at what should have been the previous version's share. Of course, that's not to say that Google and device makers should hold off on adopting a new version until the previous one has gotten even 90%, which is never going to happen. Things, however, could probably be done better.

Greener on the other side

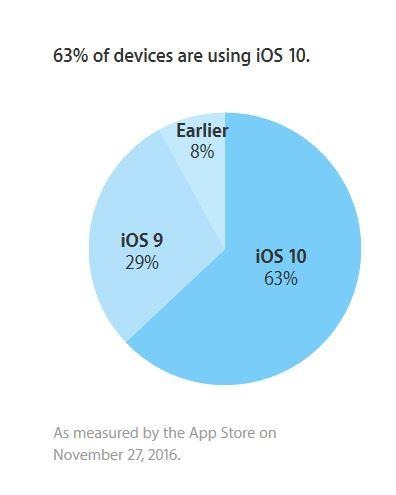

It will be difficult for Android fans to swallow, but rival iOS has a sparkling track record when it comes to getting new versions to almost everyone. Of course, there are reasons why that's possible, which we'll get to later. But for now, let's look at how things fare on the other side of the fence.

Apple didn't start sharing statistics until early 2015, so we don't have years worth of official numbers to call upon. By June of that year, iOS 8, launched in September 2014, was in full bloom. 82% for iPhones and iPads were already on that latest version, while iOS 7, which came out September 2013, was only left on 16% of devices. By the end of January this year, iOS 9 was already a good 4 months out in the wild and was already on 75% of devices, while iOS 8 scaled back to 17%. And as of late November, iOS 10 is already on 63% of smartphones and tablets, despite being only 2 months old. Those aren't small numbers at all.

The classic problem

This discrepancy wasn't loss on Android fans, who have started to demand newer Android versions at a faster pace. Fingers were pointed left and right and it reached a point where HTC thought it best to educate consumers on how Android updates, both big and small, are rolled out. And it officially confirmed what many have suspected all along. Releasing Android updates involves multiple steps and players, each of which can be stalled for an indeterminate amount of time.

In a nutshell, the pipeline goes like this. Google releases an update, be it a new Android version or a security update on its AOSP code repository as well as code dumps for its OEM partners. Manufacturers then start the process of testing and certifying the update to work on their most recent, usually one year old, devices. If all goes well, the OEM delivers the update via OTA. IF the user is lucky enough to have an unlocked model, the process ends here. For everyone else, the update will still have to pass carrier certification, testing if the new version won't break their "value added" features, before rolling out to the user. All of these can take anywhere from a few months to never.

iOS updates don't have this problem for one simple reason: Apple controls every step of the process. It is both platform maker and device maker, so there's no Google-OEM step to worry about. And while iPhones are indeed sold by carriers, it is still Apple that dictates what software goes into the device, which is to say, no carrier bloatware. Since carriers have no changes to test every iOS update against, there is no certification process to stall the rollout. At this point, it could be argued that Google has given OEMs and especially carriers too much power over Android, to the point that they can damage, and already have, Android's rep. And so Google is fighting back with a solution. Somewhat.

Pixel Fix

Google has turned a new chapter in Android history when it launched the Google Pixel phone. In addition to technical features,the Pixel is flaunting a new way of doing Android phones. To be blunt, Google is doing an Apple, being both platform and hardware maker, though it still calls upon an ODM for the actual grunt work. Software updates are its responsibility alone. Even if the Pixel has a presence on Verizon, the carrier's tinkering of updates will be very minimal. Or so Verizon swears. We still have to check back in a few months.

As good as that may sound, it really only applies to the Pixel. No other Android smartphone can boast of that, other than the Nexus, to some extent. So while Google seems to have a formula to fix Android's fragmentation problem, that will only work with its comparatively rare Pixel smartphones. Unless there comes a day when the only Android phones are Pixel phones, which is probably never going to happen. Or at least not any time soon.

Fragmentation at its worst

Android has and will always thrive on diversity. As a platform, it seems innately allergic to any attempt to close it off. At least in the present, there are too many companies, both manufacturers as well as carriers, invested in it for it to become a one-man Google show. Unfortunately, those same companies are driving both innovation and fragmentation in the Android ecosystem.

The problem with the fragmentation results in more than just delayed gratification of the nice features of new Android version. That same staged pipeline is also responsible for delays of critical security fixes. Last year's Stagefright security exploit served as a rude awakening for both Google and manufacturers, many of whom promised expedited processes for security patches. A year later, only a few of those stayed true to their word, and even then for select number of devices in select markets only. Because of that uneven distribution of security patches, even to devices just two years in the market, exploits like the recently reported Gooligan can still threaten millions of users.

Android fragmentation has become more than just a nuisance of not getting the latest features and optimizations offered by Android. It is now, more than ever, a grave threat to users' security and something that Google and OEMs are hopefully taking note of.

Wrap-up

As nice as the iOS model may be, we have to concede that it is never going to work for Android, which, in some sense, is a good thing. Android's open nature has allowed it to be used by anyone and everywhere, in ways that iOS will never be. Not without Apple's blessing. That doesn't mean, however, that Android fragmentation is something its users have to just swallow and accept as a fact of life.

Eight years. That's how long Android has been in the market. At least if you consider version 1.0. During that time, it has grown and evolved into something completely different from what it originally was. One thing that remained the same, however, was how Google, OEMs, and carriers had to work in concert to bring the software into user's devices.

Eight long years is how much the Open Handset Alliance, the collective name for official partners, have had to refine this process. Stagefright showed it was possible, with some nudging, with security updates. LG's fast rollout of new Android versions show it can also be done with larger updates. So it is all indeed possible, but requires everyone to be in sync. Hopefully it won't take another 8 years, or one or two major security disasters, before they finally get their act together.