The Untold Truth Of Friendster

There was a time, not all that long ago, when the internet was mostly chatrooms, flash games, AOL Instant Messenger, and the Hamster Dance. It was, perhaps, a cringier time, but it was also simpler. The internet hadn't yet grown into the behemoth it is today. You could access information while still being moderately sure that any behavioral missteps would be obscured behind a screen name and hidden from parents who couldn't reprogram the clock on their VCR. Then social media happened.

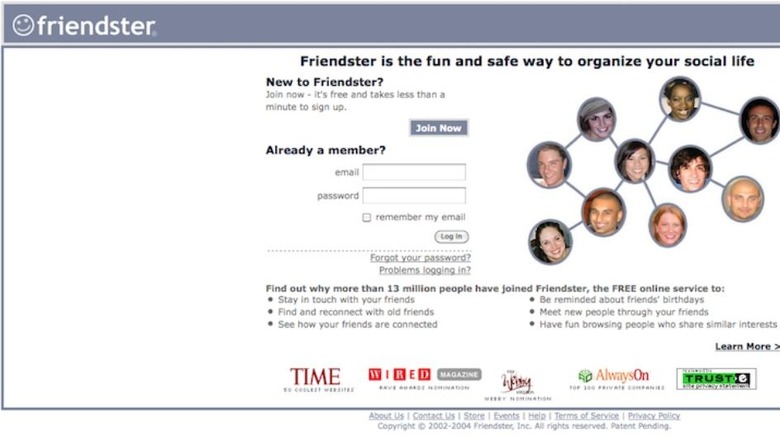

It's a ubiquitous part of our lives today. Everyone, even animals, have social media pages dedicated to their daily activities, shared with friends, family, and strangers all over the world. But before Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok, even before Myspace, there was Friendster.

In many ways, Friendster served as the digital blueprint upon which other social media platforms were built. It even attracted some pretty big names as early users. Matthew MConaughey and Senator John Kerry both had profiles, (per The Baltimore Sun). And even though he wasn't yet the famous tech mogul, even Mark Zuckerberg had a Friendster, (per Observer).

You can't look at the original layout of Facebook or Myspace without seeing Friendster's fingerprint. Sadly, it's early success wasn't enough for it to survive the ever-changing online landscape and, today, it's been largely forgotten. Here's how that happened.

Conjuring Friendster

Like so many stories in the tech world, the origin of Friendster was born out of a singular desire, not to become a billionaire tech giant, but to meet romantic partners. As explained by Wired, the story goes that in the early 2000s, Jonathan Abrams had recently ended a two-year relationship and was scrolling through Match.com, frustrated with the results. That's when a friend entered the room, returning from a serendipitous rendezvous with a romantic partner he'd met through a friend.

If only there were a way to take the "friend of a friend" experience out of the real world and put it into a digital space. That's when a lightbulb went off. Not unlike Facebook's origin as a way to rate women (pretty gross, Zuck), Friendster emerged in the mind of Abrams as a way to meet people with a tangential relationship to friends he already knew, online. After all, if you share the same friends, you might have a few things in common, right?

Abrams spent the next several months spinning up an initial version of Friendster, based on the philosophy of connecting users with mutual friends.

The founding of Friendster

The emergence of social media answered a need that the online public didn't know it had. It allowed individuals to have landing pages online, places they could direct people to connect with them, without having to build an entire website from scratch. That's what Abrams and his contemporaries were selling, the ability to connect with people.

Abrams officially founded Friendster in March of 2002 and quickly began gaining users, (per Digital Innovation and Transformation). By 2003, three million people had signed up on the nascent site. As the internet was gaining in popularity, the notion of bringing our IRL relationships online was appealing and Friendster capitalized on that desire. Users would join the site, and then invite their friends.

When those friends signed up, they could invite their friends, and the site grew. When all of your friends are at the same party, it stands to reason that you want to be there, too. The growth was natural and it continued for the next several years, until Friendster was boasting tens of millions of unique page views, (per VentureBeat). Those numbers, however, started to catch up with Abrams and, whether he knew it or not, he needed a lifeboat.

Google offers a buyout

In Silicon Valley, whenever a decently sized fish pops up in the pond, a bigger fish will inevitably attempt to swallow it up. Within a year of starting up Friendster, Abrams encountered his first big fish.

Owing to the company's near-immediate success and rapid growth, Friendster was approached by Google with an offer to buy them out, incorporating it into the Google brand, in exchange for $30 million in stock, (per ZDNet). Some might say that a $30 million payday, based on a year's worth of work is a no-brainer, but things weren't that simple.

As explained by The New York Times, Friendster had just brought in a whole group of tech investors with proven track records, having worked on companies like Amazon and Netscape, people who had helped transform business in their infancy into household names. Those investors were telling Abrams to hold his cards and wait for Friendster to become a multi-billion dollar company. So, he turned Google down.

You can always see clearest through a rearview mirror and Abrams had no way to know the gamble wouldn't pay off, but it would prove to cost him dearly. Had he taken the deal, that Google stock would be worth a cool billion dollars today.

Along comes Myspace

Friendster benefited from being the first big platform out of the gate in the early 2000s. It saw rapid initial growth because, if you wanted to connect with your friends online easily, there wasn't really anywhere else to do it. That was about to change, and quickly.

Only a few months after Friendster launched, Myspace emerged, hot on its heels. Myspace mimicked Friendster in a lot of the most important ways. It allowed users to create landing pages and share photos and information, while connecting with their friends. What really set Myspace apart, however, were the changes they made.

Myspace kept all of the parts of Friendster that worked, while changing everything that didn't. Myspace allowed users to use fake names and photographs to create their online personality, Friendster didn't. Myspace allowed users under the age of eighteen, (per Britannica) Friendster didn't. They also courted musicians, baking the early-2000s music scene into the platform's cake, all of which helped Myspace gain a foothold in the youth market.

Those features made Myspace a legitimate competitor because, at the end of the day, it was basically Friendster with a leather jacket and a fake mustache. Same basic shape, in a slightly cooler package.

Facebook: a sleeping giant

If Myspace had been the only other player in the social media space in the early 2000s, Friendster might have found a way to manage, but there was another company waiting in the wings. In 2004, only about a year after Friendster launched, and only a handful of months after Myspace joined the fray, Facebook launched.

Today, Facebook is one of the largest corporations on the planet and a recognizable name no matter where in the world you are. But in 2004, it was a small operation run by four students at Harvard, one of which was Mark Zuckerberg, you may have heard of him.

Facebook's growth was slower and more staggered than Friendster, but that's largely because it was intentionally throttled, by design. Facebook -– known as The Facebook, at the time–was initially offered only to Harvard students. Later, it was opened up to other universities and high school students. In 2006, it opened up to anyone, anywhere in the world, over the age of 13, (per Britannica).

Today, Facebook has spread all over the world, absolutely dominating the social media sphere, but back in 2004 Friendster had little reason to worry. It maintained a strong share of the market and little reason to worry about threats from outside. Little did Abrams and crew know, there was a danger to the company, and the call was coming from inside the house.

Crushed beneath their own weight

While the success or failure of any enterprise can never be laid at the feet of a single thing, it appears that a significant contributor to Friendster's struggles came from its own rapid success. Before very long, Frienster was boasting more than 100 million registered users, (per MIT Technology Review) and its servers were under considerable strain.

It wasn't uncommon for the site to become incredibly bogged down and have consistent performance issues, related both to the heavy traffic and resource-heavy features, like calculating the number of contacts two or three degrees away from a user. If Friendster had course-corrected and addressed these basic user functionalities, it might have been forgiven by the user base as startup growing pains, but the site's leadership apparently had other priorities.

As explained by High Scalability, Friendster failed to maintain a consistent quality of user experience as the platform scaled. Instead, it focused on adding new functionality like internet based phone functions and integrated chats, as well as acquiring lucrative advertising partnerships.

Adding new functions and keeping the platform fresh are an important part of a social networking company's longterm survival strategy, but Friendster learned the hard way that they can't come at the cost of nailing the basic requirements of your platform. Soon, users were jumping ship to Myspace, driven in part by a lackluster experience on Friendster.

Who's flying this plane?

If Friendster suffered from a lack of clear direction and project prioritization, it might have had something to do with the veritable revolving door leading into the CEO's office. Shortly after Friendster launched, Abrams was the bell of Silicon Valley's ball, garnering multi-million dollar offers for his company. Only a few months later, his star had dulled even within the walls of Friendster and he was relieved of duty as the company's CEO. Instead, Abrams slid into a chairman role with Tim Koogle, former CEO of Yahoo, stepping in as CEO while the company looked for a more permanent replacement, (per Commerce Times).

A few months later, Scott Sassa, a former executive for NBC was named the new CEO. He had a strong track record, having run successful programs at both NBC and Turner Broadcasting prior to the move to Friendster. Still, even Sassa wasn't up to the task and left after only a year, for undisclosed reasons, (per ZDNet).

Finally, the board brought in Taek Kwon to take over as Friendster's Chief Executive in 2005, (per Los Angeles Times). Each executive had high hopes of righting the ship and, while some parts of Friendster's platform did improve, it proved to be too little, too late.

If you can't beat 'em, buy 'em

While Friendster was turning down offers to sell the company to larger firms, like Google, they weren't above trying to snap up fledgling companies who might benefit them, or present a potential threat down the road. Had things gone a little differently, Friendster might be the biggest social networking platform in the world today.

According to Jim Scheinman, an early investor in Friendster, there was a time when Friendster almost bought Facebook before it became the 800-pound-gorilla it is today, (per Business Insider). In Scheinman's own words, while he was at Friendster, he discovered a relatively small new company called The Facebook which no one had heard of. According to Scheinman, they were very close to acquiring Facebook, (per Venture Beat), but before the deal could go through, Facebook became what Facebook became and the moment had passed.

This might be the classic example of needing to address a problem before it becomes too big to handle. The runaway success of Facebook, all other factors considered, was a substantial contributor to the ultimate death of Friendster. Had things gone just a little different, Friendster might have eliminated its largest competitor before it had found any traction.

Friendster sells out

In the wake of Friendster's outage and connectivity problems, constantly shifting leadership, and the growing audiences at both Myspace and Facebook, Friendster was on the decline in the United States and seemed poised for an early death. However, it had one saving grace, a significant and loyal fanbase in Southeast Asia, (per Financial Times).

As the 2000s were coming to a close, roughly 90% of their remaining 75 million users were in Asia and the company began looking at shifting focus to servicing the users it had, rather than chasing the ones it had lost.

Ultimately, the leadership cut losses and started shopping for a buyer in Asia to take over controlling interest in the company. In late 2009, news broke that Friendster had been purchased by MOL global, a payments company in Malaysia, (per TechCrunch).At the time, the purchase price had not been released but was speculated to be in excess of $100 million. When the dust settled, the actual price turned out to be much less.

As explained byThe Edge Markets, Ganesh Mangah, then CEO of MOL Global, confirmed they paid US $39 million for 100% of Friendster. Of that, approximately $26.4 million made its way to shareholders with the remainder paying off secured debt, fees, and bonuses to Friendster's leadership.

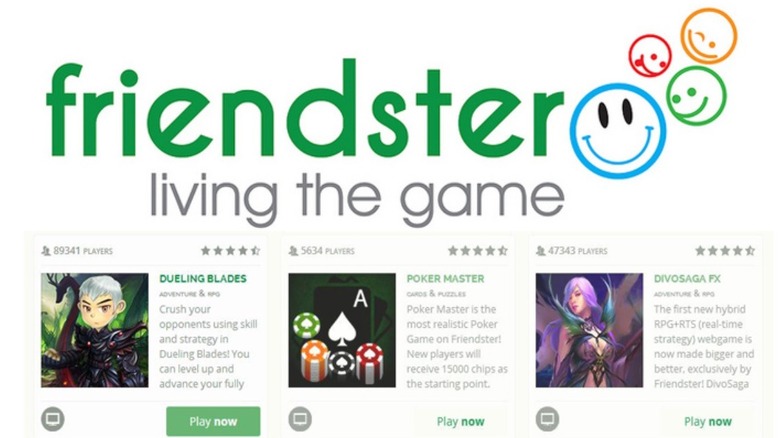

Online gaming transformation

Once MOL Global took control of Friendster, with a focus on the Asian market, it quickly shifted gears away from social networking and toward social gaming. Taking into account the recent, at the time, success of Zynga's "Farmville" on Facebook, and the significant gaming community in Asia, the move should have been a sure thing. In fact, Mangah predicted that the gaming market would be worth $5 billion within three years and intended for Friendster to take up a considerable piece of that pie, (per BBC).

The site retained the existing materials, including profiles, photos, and contacts of anyone who had already signed up, but reformatted the site to focus almost entirely on in-browser games. MOL also partnered with Facebook to incorporate a payments system, which would allow users to buy Friendster coins which could be used for in-game materials, (per Engadget).

At launch, the newly rebranded Friendster Games offered a few dozen titles ranging from casual play to Flash-based MMOs, (per Game Developer). The only question was whether the shift would help the site retain and grow their user base or not. Ultimately that would depend on whether gaming or social activity was more important. In a nutshell, did people go to Facebook for "Farmville" or did people play "Farmville" because they were already on Facebook? That was the $39 million question.

Friendster offloads patent assets

Bringing Facebook in as a partner to help implement a digital payments system for Friendster coins was an unusual choice, considering that MOL Global built themselves up as a leading online payments platform on the Asian continent. It turns out, there was a good reason for Facebook's involvement.

Over the course of Friendster's tenuous journey leading up to the sale, they developed a number of technologies for social networking and secured the associated patents. There had been talk, while Friendster was treading water in the states, that their patent portfolio might be worth more than the company itself, (per The Guardian), and that turned out to be true.

Shortly after MOL acquired Friendster, they entered into negotiations with Facebook to sell their intellectual property including seven finalized patents and eleven pending patent applications, (per VentureBeat).

That deal netted Friendster $40 million and it's likely that use of Facebook's digital payment software was bundled in the sale. The move amounted to a final piece of irony. The company they tried to buy little more than five years earlier, now owned every piece of IP Friendster had invented. For an industry which ostensibly builds itself on more robust relationships in an increasingly digital world, when push comes to shove, it's kill or be killed.

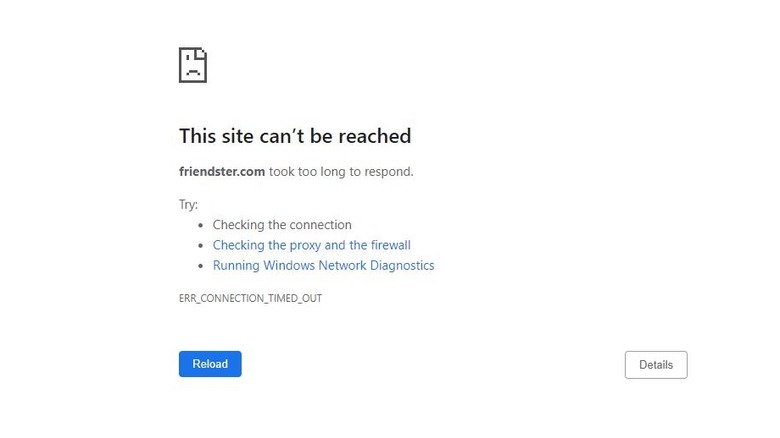

Friendster's final breath

For a brief moment, the shift to Friendster Gaming looked like it might work, giving the once-social-networking site a chance at a second life, even if only in name alone. In fact, in 2012 it was reported that Friendster Gaming was the top online gaming site in the world, (per Esquire). Not bad for a site which was hemorrhaging only a couple of years earlier.

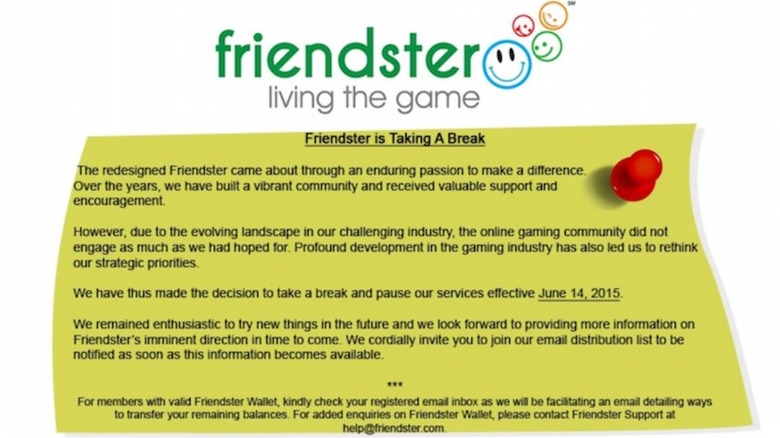

However, whatever magic it had managed to grab hold of wouldn't last. By 2015, the online landscape had changed enough, even in Asia, that Friendster could no longer sustain itself. The company slipped quiety into a state of suspended animation on June 14, 2015, when the site was unceremoniously replaced with a single landing page alerting users that Friendster was taking a break to rethink and reassess. It would never recover.

While the landing page offered a mailing list and promised updates as they emerged, none were ever forthcoming. Friendster remained in a corporate coma for three years before officially shuttering its digital doors, (per Search Engine Journal). Time of death: 2018.

Death, even the death of a company, always feels sudden but the decline of Friendster was the result of chronic problems which plagued it almost from the beginning. The online environment was changing too quickly and Friendster, the first of a new internet animal, wasn't quite adapted to its niche.