Why Did Old TVs Show Color Bars?

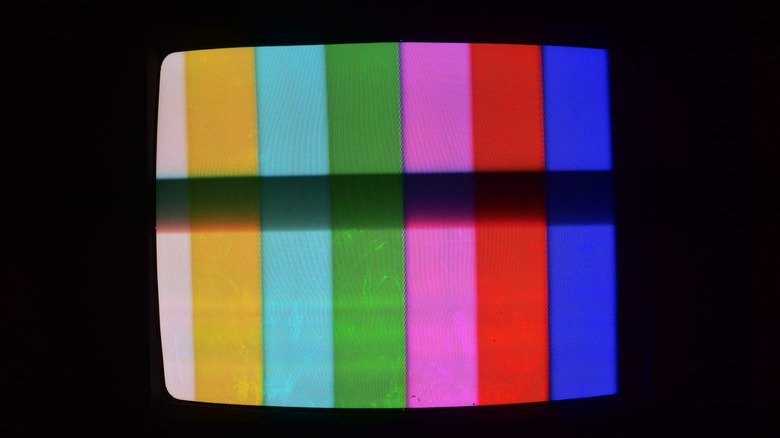

Before streaming and 24/7 programming, there was a time when TV stations actually signed off for the night. Yeah, unbelievable. You'd be watching a late movie or dozing through infomercials, and then, cut to silence, a high-pitched tone, and a stack of vivid color stripes frozen on screen. That oddly satisfying rainbow wasn't a glitch — it was a deliberate intermission, and it had a job to do.

More technically known as SMPTE color bars (after the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers), they were test patterns used to calibrate TVs. Engineers needed a visual reference to make sure color, brightness, contrast, and audio sync were accurate across devices, and these saturated stripes served that purpose. A precursor to this standard was invented and patented by RCA engineers Norbert D. Larky and David D. Holmes, but it was the SMPTE version — or Engineering Guideline (EG) 1-1990 — that became iconic.

Let's get into the finer details of why this was necessary back then, how they worked, and why they're no longer in use.

Why old TVs showed color bars

In the analog TV era, there was no baseline for how content should look on screen. Picture quality depended heavily on the individual TV's circuitry, local broadcast equipment, and signal strength. The same show could look bright and crisp on one screen, and dull or green-tinted on another. That inconsistency made it nearly impossible to ensure a viewer at home was seeing what the broadcaster intended.

The test pattern became the industry's visual reference point — a static signal that let technicians and consumers align their displays to a unified standard. If you adjusted your TV's display to match the test bars, you could be confident the colors and image quality were, at least in theory, accurate.

Before SMPTE, broadcasters used a range of black-and-white test cards — the most famous being the RCA "Indian Head" pattern from 1939. Others included the BBC's "Test Card F," starring little Carole Hersee playing tic-tac-toe with a clown doll. No matter the design, the consistent objective was visual fidelity: making sure what the viewer saw at home wasn't wildly different from what the studio sent out.

This effort was especially important under NTSC — the National Television System Committee — which developed the first color TV standard for the U.S. Viewers half-jokingly called it "Never Twice the Same Color" because keeping hues consistent from one TV to the next was a notorious challenge.

How the color bars worked (and proof they're still around today)

Each part of the test pattern did a specific job. The seven vertical bars — white, yellow, cyan, green, magenta, red, and blue, all at 75% intensity, represented precise combinations of red, green, and blue (RGB) values that helped technicians calibrate hue and saturation. If the red on your screen leaned too orange, for example, you'd adjust your settings until it aligned with the pattern image.

Beneath the main bars sat darker and lighter shades known as PLUGE signals (short for Picture Line-Up Generation Equipment). These helped fine-tune black levels and contrast. A blacker-than-black bar showed if your TV was crushing shadow detail, while a gray-ish bar helped identify if brightness was too high.

Alongside the visuals, stations would often pair a 1kHz sine wave tone — a pure audio frequency — with the pattern. That's where the phrase 'bars and tone' comes from. This sound helped engineers check for proper audio transmission and sync. A clipped version of it now lives on in YouTube blooper videos and glitchy transitions. You might also recognize it as the sound of censored obscenities.

While modern TVs rarely need manual calibration, color bars haven't disappeared completely. You'll still catch them behind the scenes at major TV networks, just in sleeker, updated forms. Even Netflix has hidden test pattern "shows" buried on the platform — tools designed to optimize things like chroma and luminance on 4K TVs. What began as a utility for analog accuracy has become both a calibration tool for the digital age and a pop culture symbol in its own right.