How Scientists Are Helping Astronauts To Get A Better Night's Sleep In Space

Going to space is hard on the human body for a number of reasons. The microgravity environment causes muscle and bone loss and leads to fluids pooling in the upper parts of the body. Being in space worsens eyesight, can alter the immune system, and can lead to nausea similar to motion sickness. Not to mention the threat of radiation, which can increase the likelihood of developing cancer and other diseases.

But there's another aspect of space that's tough for astronauts in terms of both their physical and mental health, and it's one you might not have considered: sleep. We know that sleep is vital for health here on Earth, and the same is true in space. But it's hard to get a good night's kip when you're in an environment like the International Space Station (ISS) where there are no real days or nights, and where you have to strap yourself down to your bed to prevent yourself from floating away.

Studies have shown that disrupted sleep is a very common problem among astronauts. In the history of humans living in low-Earth orbit, astronauts in older stations like Skylab in the 1970s had to get by on as little as six hours of sleep per night on average, with some operating on less than five hours on some nights. Now, even though NASA astronauts are scheduled to have eight to eight and a half hours of sleep per night on the ISS, in practice they often get much less sleep than that. Recently, a group of astronauts called Crew-7 launched on a six-month mission to stay on the ISS. As part of their work on the station, they'll be looking into sleep in space and how this could be improved.

The issue of circadian rhythms

On Earth, our sleep patterns are heavily influenced by our environment. The phrase circadian rhythms refers to a 24-hour cycle our bodies experience and which regulates how alert or sleepy we feel. This influences body temperature, hormone levels, appetite, digestion, and many other bodily functions. These rhythms are affected by cues in the environment, such as the amount of light around us and the type of that light. Basically, when there's light around you, your body thinks it is time to wake up. When it's dark, your body wants to sleep.

In space, though, there is no 24-hour day cycle. That would be a big problem for the astronauts if the lights were on and there was activity going on at all hours. So the ISS follows Greenwich Mean Time, creating a consistent schedule on which the astronauts wake up and go to sleep. However, researchers want to improve the sleeping conditions within that cycle. One idea is to use lighting to simulate different times of day, so there is a soft red glow at night like a sunset, and a bright blue in the morning like the sky.

An experiment called Circadian Light will be tested by European Space Agency astronaut Andreas Mogensen to see if the changing light conditions can help him sleep better. The light doesn't only change color at different times of the day — it also varies from day to day to simulate some days being clear and sunny and other days being overcast. The idea is to have a more varied and interesting experience in what would otherwise be a very monotonous environment.

How to bed down in microgravity

The environmental impact on sleep is one thing to consider, but another is the practical challenges of sleeping without gravity. ISS astronauts typically sleep in sleeping bags which are strapped to a wall to stop them from floating around during the night. This is apparently quite the challenge to get used to, as it doesn't involve lying down in the way we normally think of it. As there isn't really any down direction when there isn't significant gravity, astronauts can rest their bodies but they can't really lie on things.

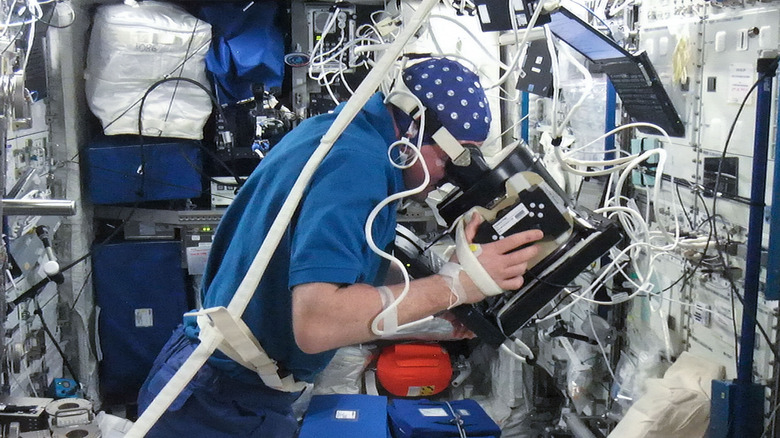

To try to understand how this affects sleep and whether the astronauts are getting good quality sleep, the traditional method has been to use an electroencephalogram (EEG) cap. This measures brain activity through a series of electrodes which are placed all over the head in a cap-like contraption. But the cap is bulky and has a lot of wires coming out of it, which people often find uncomfortable when trying to sleep.

It's not very helpful to try to measure sleep quality using a device that makes people's sleep experience worse. So a new method being tested is using a much smaller in-ear device to take EEG measurements. These devices have been tested on Earth and found to be more comfortable to use and capable of taking key sleep measurements. Now, the device will be tested by Andreas Mogensen on the ISS, in concert with the Circadian Light experiment. The idea is to test out both technologies and to share data between the two experiments, to see if sleep in space can be improved in the long term.