Springald: The Medieval Siege Weapon That Changed Warfare

During the Medieval era, armies utilized all sorts of devastating contraptions to breach fortifications such as castles. One of the most famous of these tools was the ballista. But many may not be aware of the ballista's little brother, the springald.

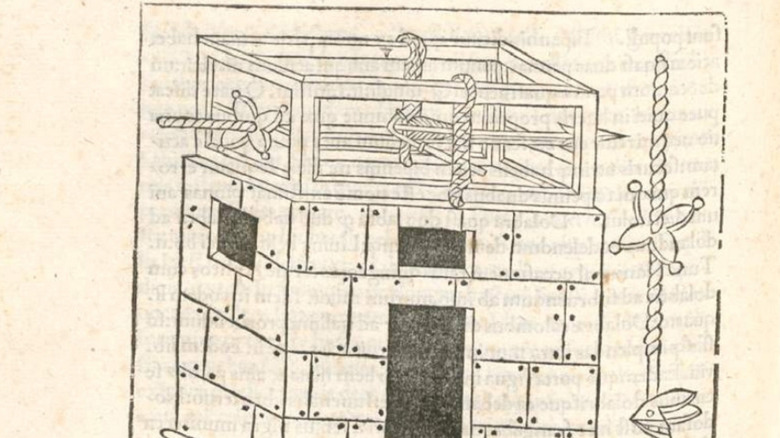

Although not as prevalent as the ballista, the springald pops up in film and television now and again. It even got a nod in the final season of "Game of Thrones." But when it is portrayed, you likely mistake it for a ballista, as both contraptions appear the same on the surface. The springald had a wooden frame, and, like the ballista, used a crank lever to create tension in a bowstring to fire a projectile from a bow mounted on top. It got its power from two bow levers inside the device. This projectile-throwing device was prominent in late 12th-century and early 13th-century siege warfare. So, what separated it from the ballista, and why was it eventually phased out?

[Featured image by Roberto Valturio (1405–1475) via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Size matters

Medieval armies used the ballista and the springald to fire projectiles over castle walls to damage troops or fortifications. However, the projectiles they fired differed. While the ballista fired arrows and large bolts, the springald fired smaller projectiles such as iron bolts, lead balls, and even Greek fire. Although less powerful, the springald had an important advantage over the ballista.

The springald was considerably smaller. This, combined with a nice set of wheels, gave it much more mobility. The springald could reach the front lines faster than the ballista, making it a better choice for artillery fire in certain cases. Some historians theorize that the device's development was directly linked to the spread of the spinning wheel across Europe. But the springald didn't always need wheels, as its compact design also made it suitable for mounting for defense. The device is said to fire around 180 meters from a tower, allowing it to defend against far-away units.

There was just one big problem with the springald; it was expensive. In their book "The myth of the mangonel: torsion artillery in the Middle Ages," Jean Liebel estimated that the springald related to the Avignon papacy cost six months of unskilled laborer wages. Its hefty price, in addition to the introduction of firearms, led to the downfall of the springald in the late 14th century. Still, it's important to remember this often-forgotten machine and how it shaped the medieval battlefield.