Honey Bees Can Be Used As Biosensors: Here's How

Research has consistently pointed to the essentiality of honeybees. From the first research to uncover bees' communicative dance language to the numerous studies showing how critical bee populations are to stable food production, bees are often found at the center of academia. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization reports that bees fuel around one-third of the global effort to cultivate food products. Likewise, a 2015 study by Bromenshenk et al. notes that pollinators (bees and other insect species) account for as much as 80% of flowering terrestrial plant reproduction across the globe.

Not only are bees adept pollination vessels that help support the larger ecosystem, but recent efforts to understand their biology suggest that they can lend their talents in many other ways. One application of bee biology, in particular, feels like it was plucked right from a science fiction novel. Researchers are experimenting with bees as biosensors to detect a vast catalog of trace chemical signatures. Like bomb and drug-sniffing dogs, bees exhibit a highly attuned sense of identification and appear to be an ideal choice for a wide range of specialized tasks.

What are biosensors, anyway?

Any attempt to understand what's going on here has to start with a brief survey of what biosensors are. A biosensor is a detection tool that can identify substances, chemicals, enzymatic processes, microorganisms, and other entities at trace levels. They are crucial in medical science, security and defense, and even sonic detection. There are breakthroughs in optical biosensor technology that promise to detect cancer. The traditional biosensor might best be exemplified in the glucose measurement tools that patients who have diabetes use routinely to maintain stable wellness.

These biosensors rely on a disposable test vehicle, however. After a test, the sensor displays the output, and the testing medium is thrown away. With honeybees as biosensors, however, the test medium (the bee itself) performs detection tasks for a short period. Then it returns to its hive to continue with the daily happenings of the bee colony. This means that the same hives and bees can be employed repeatedly without having to manufacture new test strips, substrates, or sample collectors or deal with the burden of disposal after a single use.

How did bees enter this field?

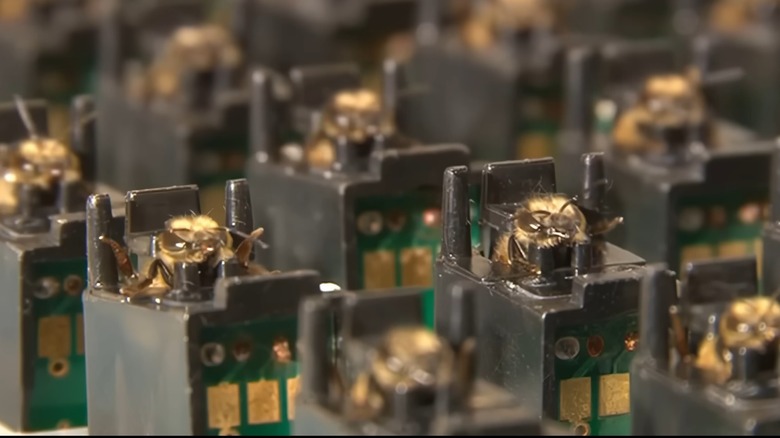

Bromenshenk and his colleagues write that Inscentinel, Ltd. began creating bee 'harnesses' in the United Kingdom around the year 2000. Since then, the outlet has been able to streamline its cassette design and the training tools that make bees a fundamentally special biosensing animal. The team notes that in previous decades of scholarship surrounding bee behavior, researchers dismissed the idea that these creatures could smell with the exacting precision they truly possess. This is largely due to the voluminous weight placed on the dance language they also exhibit. The scientific community simply didn't fully understand the multifaceted nature of bee behavior until recently (even as some researchers explored this additional avenue nearly 100 years ago).

It turns out that honeybees can sense in the range of parts per trillion, much like the sense of smell found in dogs. This makes them a fantastic natural sniffer animal for detecting all kinds of trace substances. Much like dogs, a selection process must take place before any particular bee can be used as a biosensor, however. Bees eat with the use of a tongue (called a proboscis). Many exhibit an extension reflex of their proboscis when presented with a sugar water solution, and this is the key factor that allows bees to be trained and utilized in detection tasks.

Training and maintenance procedures make bees a superior, organic biosensing tool

The research surrounding bees as biosensors is compelling. They can be leveraged to identify many chemical signatures, and the training timeline from start to finish takes less than an hour. A network of colonies (as many as 15 or more at a time) can be "conditioned in less than three days in open field settings," according to the Bromenshenk group's findings.

Bees are self-sufficient, as well. After employing any particular bee in detection duties (for a few days at a time), it is returned to the hive, where it will reintegrate into its daily life. Bees used in bomb, chemical, and other detection services can feed themselves once returned to the hive, and they don't get distracted in the same way that dogs do. Likewise, there are many reports of inaccuracies among drug-sniffing dogs. Most troubling, it appears that drug sniffer teams are even less accurate regarding minority groups, leading to many false positives. Among bees, however, large groups of biosensing bees are used as a redundancy measure to confirm findings, and handlers who might sway the animals simply aren't a part of the process.

Furthermore, tests have noted bees' ability in "free-flying" environments (rather than laboratory settings) that have successfully identified buried mines and monitored chemical pollution levels. All this suggests that bees may be even more valuable than we have yet to discover.