The 5 Largest Meteorites To Ever Hit The Earth

Meteorite impact occurs far more often than you might expect. Cosmos Magazine notes that an estimated 17 collisions occur on the Earth's surface every, single day. However, because majority of the planet is covered in water, and vast swaths of the land area remain uninhabited or sparsely populated, it can be easy to overlook these strikes. Still, the majority involve relatively small objects hurtling through the Earth's atmosphere. When they do eventually land on the surface, they have been minimized significantly by friction and burnout forces (via NASA). While the majority of impacts from meteorites involves small objects, this is not always the case. Scientific belief holds that a massive asteroid is likely responsible for the extinction of dinosaurs on our planet (via Scientific American).

The reality of meteorite impacts is that they are random and happen with an incredible frequency. when paired with the extinction level impact that scientists believe blotted out the Sun and killed off the dinosaurs, it's easy to see why asteroid, comet and meteorite movies are so popular. Similarly, NASA scientists just last month succeeded in a proof of concept test designed to understand whether or not diverting a meteorite through satellite impact is possible (as movies often utilize as their central premises).

These five meteorites are the largest known to have hit the Earth, leaving behind hulking remnants that are still studied.

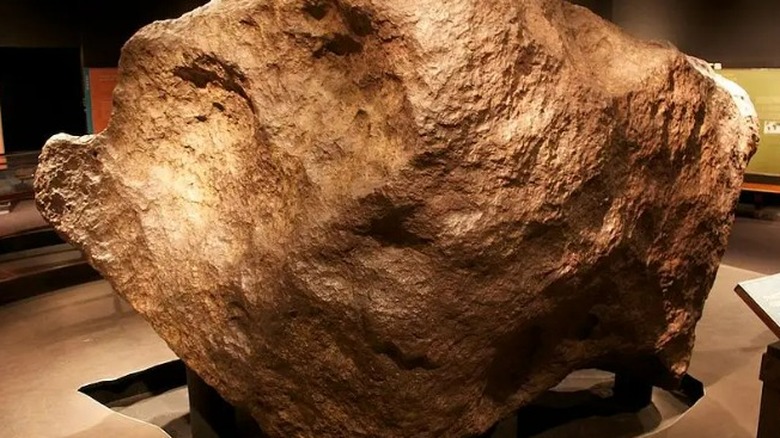

The Hoba meteorite

The Hoba meteorite is the largest single piece of space debris currently on Earth's surface: Scientists think it landed around 80,000 years ago, coming to rest in what is today Namibia, according to Info-Namibia. Hoba is about twice the weight of the next largest meteorite discovered on the planet and it is uniquely shaped, showcasing a slender, flat form rather than a round and bulbous shape. The meteorite has never been moved from its spot, and so scientists don't actually know how deep the rock is embedded in the soil. However, scientists believe that this meteorite likely crashed into the Earth at a very oblique angle, causing it to skip along the surface like a flat rock on a lake (via Geology). This would explain why such a large celestial object failed to create an enormous crater at the point of impact.

As with many meteorites discovered across the world, the Hoba meteorite was found by chance. The 60-ton rock, composed predominantly of iron, was found by a farmer who was plowing his field in 1920 (via Geology). As the story goes, he was using a traditional plow pulled by an ox and experienced a scraping sound when the metal blade came into contact with the iron meteorite. Excavation to discover what lay under the surface began, and the resulting find is the largest single meteorite known to humankind.

The Mbozi meteorite

The Mbozi meteorite was discovered in Tanzania and weighs approximately 25 tons. Some of the space objects on this list remained undiscovered for a very long time, until scientific methods located and led to the excavation of hidden gems beneath the soil. The Mbozi meteorite followed a different historical trajectory. This object was partially buried and therefore found centuries prior to its scientific cataloging. The stone has been revered as a sacred icon to local communities in the area for generations and is known as Kimondo (via TripAdvisor). Mbozi is composed of similar material to other large meteorites that have been found on earth, with 90% of its mass made of iron and about 8% nickel, according to Lonely Planet. The meteorite was found in 1930 by those of the scientific community, but as noted, has been known locally for much longer. In 1967, it was deemed a protected monument by the Tanzanian government and is now administered by the department of antiques in Tanzania.

The country is full of unique tourist destinations, including Mount Kilimanjaro, Zanzibar Island, and plenty of destinations for safari opportunities. However, the Mbozi meteorite remains one of the country's top draws.

The El Chaco meteorite is part of a larger field of fragments

The El Chaco meteorite is part of the Campo del Cielo group of meteorites found in a 60 square kilometer crater field located in Argentina. This meteorite is 37 tons and was found in 1969. Unlike the Hoba meteorite, El Chaco is far more rounded and struck at a more direct impact angle, it was therefore found five meters beneath the Earth's surface using metal detectors. Having taken a nosedive toward the Earth's surface, the meteorite and its surrounding fragments all created substantial impact craters and are buried at similar depths (one new piece was recently recovered, in fact, via Science Alert).

One unique feature of the Campo del Cielo meteorite field is that thieves continue to target the area in attempt to steal fragments of the large El Chaco meteorite and others in the area (via Scientific American). As a measure to combat this problem, the Chaco regional government declared the meteorites as cultural items of interest in 1990 in an attempt to protect this unique impact site.

Scientific American also notes that because of an almost 90-degree attack angle toward the ground, El Chaco landed at a speed of about 14,000 kilometers per hour, and alongside an enormous field of additional debris.

The Bacubirito meteorite

The Bacubirito meteorite was found in Mexico in 1863. The stone is composed mostly of iron and weighs around 20 tons. Today, Bacubirito can be found in a gallery called the Sanctuary in Sinaloa, Mexico (near its landing site). This meteorite is the third largest known, and is the longest meteorite ever discovered. The object is 4.25 meters long and roughly 2 meters wide and high (roughly 14 feet by 6.5 feet). Google Arts & Culture also notes that the Bacubirito meteorite has a unique chemical composition when compared to others discovered on the surface of Earth (also discussed by Mindat). While it's made of mostly iron, this only accounts for around 89% of its composition, with 9.6% nickel, 0.87% cobalt, and 0.14% phosphorus. The meteorite also contains traces of Iridium, a rare earth element and 117 ungrouped irons (via Google Arts & Culture).

Like other meteorites on this list, the one's significant level of iron is expected for an object of its size, but the unique composition of specific geochemical properties is striking. National Geographic notes that not all of the meteorites found on Earth are composed of high levels of iron, but the massive stones that humans have uncovered are almost exclusively iron-dominated. This gives them the ability to withstand intense temperature and pressure changes as they make their way through the atmosphere and toward the surface of the planet.

The Cape York meteorite

The Cape York meteorite landed on earth about 10,000 years ago, and its history is uniquely tied into the development of human civilization in the region.

What sets it apart from other celestial objects that have crashed into the surface of the Earth, is that it was clearly found and utilized by humans for thousands of years before being identified by the scientific community (via the University of Washington). The meteorite weighs about 20 tons and shows distinctive signs of scraping and breakage from local area inhabitants who used it to make tools. This makes the meteorite an integral part of early human civilization and the great history of ancient human society in pre-contact North America. Like other meteorites on this list, the Cape York stone is composed primarily of iron, allowing it to fall through Earth's atmosphere without experiencing extreme breakup, according to the University of Washington.

This meteorite is still fragmented however, and pieces of it can be seen in a number of locations around North America. The American Museum of Natural History has three fragments of the Cape York meteorite on display, named The Woman, The Dog, and Ahnighito (via AMNH). What's interesting about these individual fragments is that they were recovered from various impact sites, with one separated from the others and located on an island across the bay from the primary point of impact. The largest fragment of this meteorite can be seen in the geological Museum of the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.